TED日本語

TED Talks(英語 日本語字幕付き動画)

TED日本語 - ケイラ・ブリエット: 私がアートを制作するのは、伝統を受け継ぐタイムカプセルを作るため

TED Talks

私がアートを制作するのは、伝統を受け継ぐタイムカプセルを作るため

Why do I make art? To build time capsules for my heritage

ケイラ・ブリエット

Kayla Briet

内容

ケイラ・ブリエットは、アイデンティティと自己発見と、いつしか自分の文化が忘れ去られることへの恐怖心を模索するアートの制作者です。ケイラは、自分がどのようにして、自分の創造的な声を見つけ出し、声や物語を映像と音楽のタイムカプセルに組み込むことで、オランダ系インドネシア人と中国人とアメリカ先住民としての自分の物語を取り戻したかについて語ります。

字幕

SCRIPT

Script

When I was four years old, my dad taught me the Taos Pueblo Hoop Dance, a traditional dance born hundreds of years ago in Southwestern USA. A series of hoops are created out of willow wood, and they're threaded together to create formations of the natural world, showing the many beauties of life. In this dance, you're circling in a constant spin, mimicking the movement of the Sun and the passage of time. Watching this dance was magic to me. Like with a time capsule, I was taking a look through a cultural window to the past. I felt a deeper connection to how my ancestors used to look at the world around them.

Since then, I've always been obsessed with time capsules. They take on many forms, but the common thread is that they're uncontrollably fascinating to us as human beings, because they're portals to a memory, and they hold the important power of keeping stories alive. As a filmmaker and composer, it's been my journey to find my voice, reclaim the stories of my heritage and the past and infuse them into music and film time capsules to share.

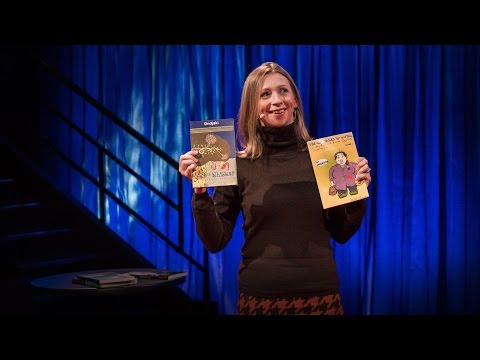

To tell you a bit about how I found my voice, I'd like to share a bit about how I grew up. In Southern California, I grew up in a multigenerational home, meaning I lived under the same roof as my parents, aunts, uncles and grandparents. My mother is Dutch-Indonesian and Chinese with immigrant parents, and my father is Ojibwe and an enrolled tribal member of the Prairie Band's Potawatomi Tribe in Northeastern Kansas. So one weekend I'd be learning how to fold dumplings, and the next, I'd be traditional-style dancing at a powwow, immersed in the powerful sounds of drums and singers. Being surrounded by many cultures was the norm, but also a very confusing experience. It was really hard for me to find my voice, because I never felt I was enough -- never Chinese, Dutch-Indonesian or Native enough. Because I never felt I was a part of any community, I sought to learn the stories of my heritage and connect them together to rediscover my own.

The first medium I felt gave me a voice was music. With layers of sounds and multiple instruments, I could create soundscapes and worlds that were much bigger than my own. Through music, I'm inviting you into a sonic portal of my memories and emotions, and I'm holding up a mirror to yours. One of my favorite instruments to play is the guzheng zither, a Chinese harp-like instrument. While the hoop dance is hundreds of years old, the guzheng has more than 2,000 years of history. I'm playing the styles that greatly influence me today, like electronic music, with an instrument that was used to play traditional folk music long ago. And I noticed an interesting connection: the zither is tuned to the pentatonic scale, a scale that is universally known in so many parts of music around the world, including Native American folk songs. In both Chinese and Native folk, I sense this inherent sound of longing and holding onto the past, an emotion that greatly drives the music I create today.

At the time, I wondered if I could make this feeling of immersion even more powerful, by layering visuals and music -- visuals and images on top of the music. So I turned to internet tutorials to learn editing software, went to community college to save money and created films.

After a few years experimenting, I was 17 and had something I wanted to tell and preserve. It started with a question: What happens when a story is forgotten? I lead with this in my latest documentary film, "Smoke That Travels," which immerses people into the world of music, song, color and dance, as I explore my fear that a part of my identity, my Native heritage, will be forgotten in time.

Many indigenous languages are dying due to historically forced assimilation. From the late 1800s to the early 1970s, Natives were forced into boarding schools, where they were violently punished if they practiced traditional ways or spoke their native language, most of which were orally passed down. As of now, there are 567 federally recognized tribes in the United States, when there used to be countless more. In my father's words, "Being Native is not about wearing long hair in braids. It's not about feathers or beadwork. It's about the way we all center ourselves in the world as human beings."

After traveling with this film for over a year, I met indigenous people from around the world, from the Ainu of Japan, Sami of Scandinavia, the Maori and many more. And they were all dealing with the exact same struggle to preserve their language and culture.

At this moment, I not only realize the power storytelling has to connect all of us as human beings but the responsibility that comes with this power. It can become incredibly dangerous when our stories are rewritten or ignored, because when we are denied identity, we become invisible. We're all storytellers. Reclaiming our narratives and just listening to each other's can create a portal that can transcend time itself.

Thank you.

(Applause)

4歳のとき 父が私に タオス・プエブロの フープダンスを教えてくれました この伝統舞踊は 何百年も前に 合衆国の南西部で 生まれたものです 一連のフープは 柳の木から作られていて これらの輪を組み合わせることで 森羅万象を様々な形にして 生命の様々な美しさを表します このダンスは 一定の速さで回りながら 太陽の動きや 移りゆく時を模倣します このダンスをみて 私はとりこになりました まるでタイムカプセルで 文化という窓から 過去を 垣間見たような思いでした 私は 深いつながりを感じました それは 祖先の世界観へのつながりでした

それ以来 私はずっと タイムカプセルに夢中です 形は様々でありながら その共通点は 私たち人類にとって 抑えがたい魅力があることです なぜなら タイムカプセルは 記憶への入り口であり 物語を生かし続けるという 大切な力があるからです 映画製作者として作曲家として 私が続けている旅は 自分の「声」を見つけ 受け継いだ伝統や 過去の物語を取り戻し融合させて 音楽と映画の形のタイムカプセルに 入れて 人々に伝えることでした

自分の「声」を見つけた経緯を お伝えするために 私の生い立ちを少し お話ししたいと思います 私は 南カリフォルニアで 多世代が暮らす家に育ちました それは 1つ屋根の下に 両親、おじおば、祖父母が 一緒に暮らす家でした 母は オランダ系インドネシア人と 中国人の移民の両親の間に生まれ 父は アメリカ先住民 オジブワ族で 部族メンバーとして登録された プレーリー・バンド・ポタワトミという カンザス北東部の部族の一員です ですから 私はある週末には 点心の包み方を習い 次の週末には パウワウの集会で 伝統様式のダンスを習い ドラムと歌い手の 力強い音に 慣れ親しみました 多文化に囲まれることは 当たり前のことであると同時に 困惑する経験でした 自分の声を見つけるのは とても難しいことでした 私は 中国人としても オランダ系インドネシア人としても アメリカ先住民としても 十分だと感じたことがなかったからです 私は どの社会に対しても 帰属意識が持てなかったので 文化的に受け継いだ物語を学び つなぎ合わせることで 自分を再発見しようと努めました

自分の声を 授かったと感じた 初めての手段が音楽でした 幾重にも織りなす音と いくつもの楽器を用いることで 私は それまでよりもずっと大きな 世界と音の風景を作り出せたのです 音楽を通じて みなさんを 私の記憶と感情の入口へと誘い みなさんの記憶と感情を 映し出したいと思います 私が 好んで演奏する楽器の1つは 古箏という ハープに似た 中国の楽器です フープダンスが 数百年の歴史を持つのに対し 古箏には 2千年以上の歴史があります 私は 今の自分が大きな影響を受けた 音楽のスタイル ― 例えば電子音楽を かつて伝統的な民族音楽で使われた 楽器で演奏しています そして私はある興味深い つながりに気づきました 古箏は「5音の音階」に 調律されますが この音階は 世界中の 様々なジャンルの音楽に 広く知られていて そこには アメリカ先住民族の 音楽も含まれています 中国の民謡にも 先住民族の音楽にも 私は 過去を切望し 過去にすがるような この独特の響きを 感じています この感情に大きく触発されて 今の私は音楽を作っています

その時に 私は ひょっとしたらこの一体感を 映像と音声を重ね合わせ 音楽の上に映像と画像を載せることで さらに 強調できるのではないかと考えました オンラインでソフト編集を学び 大学は 地域の短大に通うことで お金を貯めて 映画制作をしました

2、3年実験的な制作をした後 17歳の時に 語りついで残したいと 思えるものに出会いました それは1つの問いで始まりました 「物語が忘れられたら どうなるのか?」 その問いから 監督指揮に至ったのが 最新ドキュメンタリ映画 『Smoke That Travels』です それは 見る人を 音楽と歌と 色と舞踏の世界に引き込みながら 私の独自性の根幹をなす 先祖から受け継いだ先住民としてのあり方が 忘れられることへの恐怖心を 掘り下げます

先住民の言語が多く失われつつあるのは 過去に同化政策が行われたせいです 1800年代末から1970年代初頭まで 先住民は 寄宿学校に強制収容され 伝統的なしきたりを実践したり 母語を使ったりすると ― ほとんどが 口伝伝承でした ― 暴力的に罰せられました 現在 アメリカ合衆国には 連邦政府に認知された部族が567います かつては 無数の部族がいたというのに 父の言葉によれば 「先住民族のアイデンティティは 髪を長い三つ編みにすることではない 羽根飾りや ビーズ刺繍のことではない 私たちが皆 人として自己を世界の 中心に位置づけられるかどうかだ」

私は この映画を携えて 1年以上 各地を旅して 世界中の先住民の人に会いました 日本のアイヌや スカンジナビアのサミ族や マオリ族などなど もっと沢山会いました するとどの民族も 全く同じ 大きな課題を抱えていました それは 自分たちの ことばと文化を守ることです

今の私は 物語が持つ 私たち人類を 皆結びつける力に気づくと共に この力に伴う責任にも 気づいています 物語が 書き換えられたり蔑ろにされたら 非常に危険な事態になり得ます なぜなら アイデンティティを否定されたら 透明人間になってしまうからです 私たちは皆 物語の語り手です 私たちが 物語を取り戻し 互いの声にちょっと耳を傾ければ その行為自体が 時を超越できる糸口となり得ます

ありがとうございました

(拍手)

品詞分類

- 主語

- 動詞

- 助動詞

- 準動詞

- 関係詞等

TED 日本語

TED Talks

関連動画

アーティストは経済にどう貢献し、私たちは彼らをどう支えられるか?ハディ・エルデベック

2018.04.09

コンテンツを流行らせる要素とは?ダオ・グエン

2018.01.08

ニューヨーカー誌、象徴的な表紙イラストの舞台裏フランソワーズ・ムーリー

2017.08.17

とらえ難い心情を表す素敵な新語の数々ジョン・ケーニック

2017.03.31

2千本のおくやみ記事から学んだことラックス・ナラヤン

2017.03.23

メロドラマが教えてくれる4つの大げさな人生訓ケイト・アダムス

2017.01.03

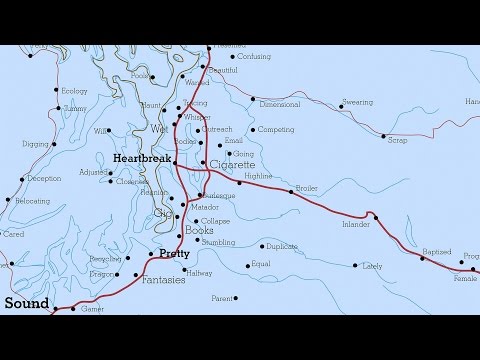

音楽がもたらしたコンピューターの発明スティーヴン・ジョンソン

2016.12.09

Ideas worth dating -- デートする価値のあるアイデアレイン・ウィルソン

2016.10.30

購読解除の苦悩!ジェイムズ・ヴィーチ

2016.09.27

コスプレへの愛アダム・サヴェッジ

2016.08.23

「アンチ」を科学的に分類してみようネギン・ファルサド

2016.07.05

データで描く、示唆に富む肖像画ルーク・デュボワ

2016.05.19

詐欺メール 返信すると どうなるかジェイムズ・ヴィーチ

2016.02.01

世界中の国の本を1冊ずつ読んでいく私の1年アン・モーガン

2015.12.21

日常の音に隠された思いがけない美とはメクリト・ハデロ

2015.11.10

アメリカで最も白人主義的な町々に突入!リッチ・ベンジャミン

2015.08.11

洋楽 おすすめ

RECOMMENDS

洋楽歌詞

ステイザ・キッド・ラロイ、ジャスティン・ビーバー

洋楽最新ヒット2021.08.20

スピーチレス~心の声ナオミ・スコット

洋楽最新ヒット2019.05.23

シェイプ・オブ・ユーエド・シーラン

洋楽人気動画2017.01.30

フェイデッドアラン・ウォーカー

洋楽人気動画2015.12.03

ウェイティング・フォー・ラヴアヴィーチー

洋楽人気動画2015.06.26

シー・ユー・アゲインウィズ・カリファ

洋楽人気動画2015.04.06

シュガーマルーン5

洋楽人気動画2015.01.14

シェイク・イット・オフテイラー・スウィフト

ポップス2014.08.18

オール・アバウト・ザット・ベースメーガン・トレイナー

ポップス2014.06.11

ストーリー・オブ・マイ・ライフワン・ダイレクション

洋楽人気動画2013.11.03

コール・ミー・メイビーカーリー・レイ・ジェプセン

洋楽人気動画2012.03.01

美しき生命コールドプレイ

洋楽人気動画2008.08.04

バッド・デイ~ついてない日の応援歌ダニエル・パウター

洋楽人気動画2008.05.14

サウザンド・マイルズヴァネッサ・カールトン

洋楽人気動画2008.02.19

イッツ・マイ・ライフボン・ジョヴィ

ロック2007.10.11

アイ・ウォント・イット・ザット・ウェイバックストリート・ボーイズ

洋楽人気動画2007.09.14

マイ・ハート・ウィル・ゴー・オンセリーヌ・ディオン

洋楽人気動画2007.07.12

ヒーローマライア・キャリー

洋楽人気動画2007.03.21

オールウェイズ・ラヴ・ユーホイットニー・ヒューストン

洋楽人気動画2007.02.19

オネスティビリー・ジョエル

洋楽人気動画2005.09.16