TED日本語

TED Talks(英語 日本語字幕付き動画)

TED日本語 - アン・モーガン: 世界中の国の本を1冊ずつ読んでいく私の1年

TED Talks

世界中の国の本を1冊ずつ読んでいく私の1年

My year reading a book from every country in the world

アン・モーガン

Ann Morgan

内容

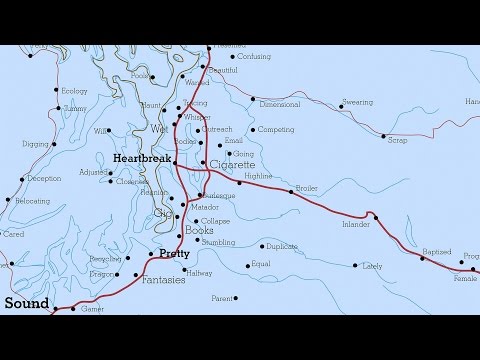

アン・モーガンは多読家だと自認していましたが、それは自分の本棚にある「巨大な文化的盲点」を発見するまでのことでした。数多くの英米作家が並ぶ中、英語圏以外の作家の作品はごくわずかしかなかったのです。そこで彼女は野心的な目標を設定します。1年かけて、世界中の全ての国の本を1冊ずつ読むことにしたのです。現在彼女は、自国語びいきの人々に翻訳書を読むよう促していて、出版社が海外の傑作をもっと届けてくれるようになるのを願っています。彼女の読書の旅のインタラクティブ・マップをこちらでご覧いただけます。go.ted.com/readtheworld

字幕

SCRIPT

Script

It's often said that you can tell a lot about a person by looking at what's on their bookshelves. What do my bookshelves say about me? Well, when I asked myself this question a few years ago, I made an alarming discovery. I'd always thought of myself as a fairly cultured, cosmopolitan sort of person. But my bookshelves told a rather different story. Pretty much all the titles on them were by British or North American authors, and there was almost nothing in translation. Discovering this massive, cultural blind spot in my reading came as quite a shock.

And when I thought about it, it seemed like a real shame. I knew there had to be lots of amazing stories out there by writers working in languages other than English. And it seemed really sad to think that my reading habits meant I would probably never encounter them. So, I decided to prescribe myself an intensive course of global reading. 2012 was set to be a very international year for the UK; it was the year of the London Olympics. And so I decided to use it as my time frame to try to read a novel, short story collection or memoir from every country in the world. And so I did. And it was very exciting and I learned some remarkable things and made some wonderful connections that I want to share with you today.

But it started with some practical problems. After I'd worked out which of the many different lists of countries in the world to use for my project, I ended up going with the list of UN-recognized nations, to which I added Taiwan, which gave me a total of 196 countries. And after I'd worked out how to fit reading and blogging about, roughly,four books a week around working five days a week,

I then had to face up to the fact that I might even not be able to get books in English from every country. Only around 4.5 percent of the literary works published each year in the UK are translations, and the figures are similar for much of the English-speaking world. Although, the proportion of translated books published in many other countries is a lot higher. 4.5 percent is tiny enough to start with, but what that figure doesn't tell you is that many of those books will come from countries with strong publishing networks and lots of industry professionals primed to go out and sell those titles to English-language publishers. So, for example, although well over 100 books are translated from French and published in the UK each year, most of them will come from countries like France or Switzerland. French-speaking Africa, on the other hand, will rarely ever get a look-in.

The upshot is that there are actually quite a lot of nations that may have little or even no commercially available literature in English. Their books remain invisible to readers of the world's most published language. But when it came to reading the world, the biggest challenge of all for me was that fact that I didn't know where to start. Having spent my life reading almost exclusively British and North American books, I had no idea how to go about sourcing and finding stories and choosing them from much of the rest of the world. I couldn't tell you how to source a story from Swaziland. I wouldn't know a good novel from Namibia. There was no hiding it -- I was a clueless literary xenophobe. So how on earth was I going to read the world?

I was going to have to ask for help. So in October 2011, I registered my blog, ayearofreadingtheworld.com, and I posted a short appeal online. I explained who I was, how narrow my reading had been, and I asked anyone who cared to to leave a message suggesting what I might read from other parts of the planet. Now, I had no idea whether anyone would be interested, but within a few hours of me posting that appeal online, people started to get in touch. At first, it was friends and colleagues. Then it was friends of friends. And pretty soon, it was strangers.

Four days after I put that appeal online, I got a message from a woman called Rafidah in Kuala Lumpur. She said she loved the sound of my project, could she go to her local English-language bookshop and choose my Malaysian book and post it to me? I accepted enthusiastically, and a few weeks later, a package arrived containing not one, but two books -- Rafidah's choice from Malaysia, and a book from Singapore that she had also picked out for me. Now, at the time, I was amazed that a stranger more than 6,000 miles away would go to such lengths to help someone she would probably never meet.

But Rafidah's kindness proved to be the pattern for that year. Time and again, people went out of their way to help me. Some took on research on my behalf, and others made detours on holidays and business trips to go to bookshops for me. It turns out, if you want to read the world, if you want to encounter it with an open mind, the world will help you. When it came to countries with little or no commercially available literature in English, people went further still.

Books often came from surprising sources. My Panamanian read, for example, came through a conversation I had with the Panama Canal on Twitter. Yes, the Panama Canal has a Twitter account. And when I tweeted at it about my project, it suggested that I might like to try and get hold of the work of the Panamanian author Juan David Morgan. I found Morgan's website and I sent him a message, asking if any of his Spanish-language novels had been translated into English. And he said that nothing had been published, but he did have an unpublished translation of his novel "The Golden Horse." He emailed this to me, allowing me to become one of the first people ever to read that book in English.

Morgan was by no means the only wordsmith to share his work with me in this way. From Sweden to Palau, writers and translators sent me self-published books and unpublished manuscripts of books that hadn't been picked up by Anglophone publishers or that were no longer available, giving me privileged glimpses of some remarkable imaginary worlds. I read, for example, about the Southern African king Ngungunhane, who led the resistance against the Portuguese in the 19th century; and about marriage rituals in a remote village on the shores of the Caspian sea in Turkmenistan. I met Kuwait's answer to Bridget Jones.

(Laughter)

And I read about an orgy in a tree in Angola.

But perhaps the most amazing example of the lengths that people were prepared to go to to help me read the world, came towards the end of my quest, when I tried to get hold of a book from the tiny, Portuguese-speaking African island nation of Sao Tome and Principe. Now, having spent several months trying everything I could think of to find a book that had been translated into English from the nation, it seemed as though the only option left to me was to see if I could get something translated for me from scratch. Now, I was really dubious whether anyone was going to want to help with this, and give up their time for something like that. But, within a week of me putting a call out on Twitter and Facebook for Portuguese speakers, I had more people than I could involve in the project, including Margaret Jull Costa, a leader in her field, who has translated the work of Nobel Prize winner Jose Saramago. With my nine volunteers in place, I managed to find a book by a Sao Tomean author that I could buy enough copies of online. Here's one of them. And I sent a copy out to each of my volunteers. They all took on a couple of short stories from this collection, stuck to their word, sent their translations back to me, and within six weeks, I had the entire book to read.

In that case, as I found so often during my year of reading the world, my not knowing and being open about my limitations had become a big opportunity. When it came to Sao Tome and Principe, it was a chance not only to learn something new and discover a new collection of stories, but also to bring together a group of people and facilitate a joint creative endeavor. My weakness had become the project's strength.

The books I read that year opened my eyes to many things. As those who enjoy reading will know, books have an extraordinary power to take you out of yourself and into someone else's mindset, so that, for a while at least, you look at the world through different eyes. That can be an uncomfortable experience, particularly if you're reading a book from a culture that may have quite different values to your own. But it can also be really enlightening. Wrestling with unfamiliar ideas can help clarify your own thinking. And it can also show up blind spots in the way you might have been looking at the world.

When I looked back at much of the English-language literature I'd grown up with, for example, I began to see how narrow a lot of it was, compared to the richness that the world has to offer. And as the pages turned, something else started to happen, too. Little by little, that long list of countries that I'd started the year with, changed from a rather dry, academic register of place names into living, breathing entities.

Now, I don't want to suggest that it's at all possible to get a rounded picture of a country simply by reading one book. But cumulatively, the stories I read that year made me more alive than ever before to the richness, diversity and complexity of our remarkable planet. It was as though the world's stories and the people who'd gone to such lengths to help me read them had made it real to me. These days, when I look at my bookshelves or consider the works on my e-reader, they tell a rather different story. It's the story of the power books have to connect us across political, geographical, cultural, social, religious divides. It's the tale of the potential human beings have to work together.

And, it's testament to the extraordinary times we live in, where, thanks to the Internet, it's easier than ever before for a stranger to share a story, a worldview, a book with someone she may never meet, on the other side of the planet. I hope it's a story I'm reading for many years to come. And I hope many more people will join me. If we all read more widely, there'd be more incentive for publishers to translate more books, and we would all be richer for that.

Thank you.

(Applause)

その人について 知りたければ 本棚を見ればよいと よく言います 私の本棚は 私について 何を語るのでしょう? 数年前にそう自問したとき 大変なことに 気づいてしまいました それまでずっと 自分は 結構教養のある 国際的視野を持つ人間だと 思っていました でも私の本棚が語っていたのは それとはかなり違いました そこにあった本の ほとんどは 英国か北米の 作家によるもので 翻訳書は ほとんど ありませんでした 自分のしている読書に この巨大な文化的盲点を発見して かなり衝撃を受けました

これは本当に 恥ずかしいことだと思いました 英語以外の言語を使う 作家による 素晴らしい本がたくさん あるはずなのは 分かっていて 自分の読書の仕方では それに出会えないんだと思うと とても残念に思いました それで 私が己に課したのは 国際的読書の集中コースです 2012年は英国にとって 国際的な年になるはずでした ロンドン・オリンピックの年ですから そこで私はこの年の間に 世界のあらゆる国で書かれた 小説とか短編集 自叙伝なんかを 読んでやろうと思ったんです そして実行しました すごくワクワクしました 驚くべき学びがあり 人との素晴らしい 繋がりができました それを今日 お話ししたいと思います

でもいざ実行となると ちょっとした問題にぶつかりました いろいろある 世界の国の一覧のうち 自分の計画には どれを使ったらいいか迷って 結局 国連が認めている 国のものにしました それに台湾を加え 全部で196か国になりました それから読書とブログ執筆の スケジュールを考えました 週あたり4冊の本を 週5日でこなしていくんです

そこで直面したのは 全ての国から英語の本を入手するのは そもそも不可能かもしれない という現実でした 英国で毎年出版される 文学作品のうち 翻訳書は約4.5%にすぎません この数字は 英語圏の多くの国で同様ですが それ以外の国の多くでは 翻訳書の割合が はるかに高いのです 4.5%という数字は すでに十分小さいのですが この数字からでは 気づきにくいことは それらの本の多くは それを英語圏の出版社に 売り込める 強力な出版ネットワークや 多くの業界人を擁する 国からのものだということです ですから例えば 英国では フランス語から翻訳された本が 毎年100冊以上 出版されていますが その大半は フランスや スイスといった国のものです 一方 フランス語圏 アフリカの国には ほとんど出版の 見込みがありません

結局は 英語で読める作品が ほとんど あるいは 全く出ていない国も 実際 非常に多いのです 世界最大の出版言語の 読者にとっては それらの国の本は 見えないも同然です でも 世界の本を読む計画で 一番難問だったのは どこから始めたらいいのか 見当も付かないことでした 生まれてこの方ずっと ほとんど英国と北米の本しか 読んでこなかったので どうやって世界の他の地域から 情報を集め 本を探し 選んだらいいのか 私には全く分かりませんでした スワジランドの物語の 情報を得る方法も ナミビアの優れた小説のことも 知りませんでした 隠しようもありません 私は何も知らない 外国文学嫌いだったんです では一体どうすれば 世界中の本を読めるのでしょう?

助けを求める 必要がありました それで2011年10月に ブログを始めました 「世界を読む1年」です (ayearofreadingtheworld.com) そして短いお願い文を 投稿しました 自己紹介をし 自分の読書の幅が いかに狭かったかを説明し 気にかけてくれる人たちに 世界の他地域の本の どれを読んだらいいか 意見をお願いしました 興味を持ってくれる人なんているのか 全く分かりませんでしたが お願いを投稿して 数時間もしないうちに 連絡が届き始めました 最初は友達や仕事仲間からで それから友達の友達 そのうち見知らぬ人からも 来るようになりました

お願い文を載せた4日後 クアラルンプールのラフィダという女性から メッセージを受け取りました 彼女は私の計画に 好印象を抱いたと言い 英語の本を扱う 地元の本屋に行って マレーシアの本を選んで 送りましょうか?と言うのです 私は諸手を挙げて歓迎しました 数週間後 小包が届き 中には1冊ではなく 2冊の本が入っていました ラフィダが選んでくれた マレーシアの本と それにもう1冊は シンガポールの本です その時 私は 1万キロ以上離れた所の 見知らぬ人が 一生会うこともないだろう 人間のために そこまでしてくれたことに 驚きました

でもラフィダのような親切を その1年 繰り返し経験することになりました 何度も何度も 人々が私を助けようと 余分な手間をかけてくれたんです 私の代わりに 調べてくれた人や 休日や出張のついでに 回り道して 本屋に行ってくれた 人もいました もし世界中の本を 読みたければ 心を開いて 出会うことを望むなら 世界中が 手助けしてくれるんです 英語になっている作品が ほとんど あるいは全く 手に入らないような国では 人々は さらに親切でした

しばしば意外なところが 本の出どころになりました 例えば パナマの本は 私がパナマ運河と Twitterで交わした会話から 得られました ええ パナマ運河にも Twitterアカウントがあるんです 私が自分の計画について ツイートしたとき パナマ運河は パナマ作家 ファン・ダヴィ・モルガンの作品なら 気に入るかもしれないと 提案してくれました モルガンのウェブサイトを見つけて メッセージを送り 彼のスペイン語の小説で 英訳されたものがないか 尋ねました すると彼は 出版されたものはないけれど 小説 『黄金の馬』 の 未刊行の翻訳なら あると言いました 彼はそれを私にメールして 私を 英語でその本を読む 最初の人間にしてくれたんです

このような形で 作品を紹介してくれた文筆家は モルガンだけでは ありませんでした スウェーデンからパラオに至るまで 作家や翻訳者の人たちが 自費出版の本や 未出版の原稿を 送ってくれました それは英語主体の出版社では 取り上げられなかったり もう絶版になっていた本で 素晴らしい想像の世界を 垣間見る特権を私に与えてくれました 例えば私は 19世紀にポルトガルに抵抗した ングングニャーネという 南アフリカの王について 読みました トルクメニスタンのカスピ海沿岸にある 僻地の村における 結婚の風習についても 読みました ブリジット・ジョーンズの クウェート版にも出会いました

(笑)

それからアンゴラの 樹上での乱痴気騒ぎについても読みました

でも 私が世界中の 本を読むのを手伝おうと 人々が骨折ってくれた 最も驚くべき例は 旅路の終盤に やってきました サントメ・プリンシペという ポルトガル語圏アフリカの 小さな島国の本を 入手しようと試みたときです この国の英訳された作品を見つけようと 思いつく限りの方法を 試みること数か月 残された唯一の方法は 私のために一から訳してくれる 人がいないか探すことのようでした そこまで時間をかけて 手伝ってくれる人が いようとは とても思えませんでした でもTwitterとFacebookで ポルトガル語のできる人を募ったら 1週間のうちに必要以上の 人が集まったんです その中には この分野の第一人者 マーガレット・ジュル・コスタもいました ノーベル賞作家 ジョゼ・サラマーゴの 作品を翻訳している人です 9人のボランティアと一緒に インターネットで 十分な部数を購入できる サントメ人作家の本を なんとか見つけました これが その1冊です 私はその本を 各ボランティアに配りました 各人がこの本の短編を 2篇ずつ担当し 約束通り できた翻訳を 送ってくれました 6週間もせず 私は 本を丸1冊手にしていました

世界の本を読む1年で たびたび発見したことですが ここでも 私の無知と 自分の限界を明け透けにすることが 大きな機会につながりました サントペ・プリンシペの件で言えば それは新しいことを学び 新しい物語のコレクションを 発見する機会だっただけでなく 一群の人々を集め 共同での創造的挑戦へと向かう 機会でもありました 私の弱点が このプロジェクトでは 強みになったのです

この年に読んだ本は 多くの点で目を開かせてくれました 読書を楽しむ人なら 知っているように 本には 私たちを 自分の外に引っ張り出して 他人の心の中に投げ込む 素晴らしい力があります それによって 束の間かもしれませんが 違った視点で 世界を見ることができます それは居心地が 悪い場合もあります とくにその本が 自分とは大きく異なる 価値観を持つ文化の ものの場合には でも そこには大きな 学びの可能性があります 馴染みのない考えと格闘することで 自分の考えが明確になります そしてまた 世界を見る上での 盲点が露わにもなります

私が共に育ってきた 英語作品の多くを 思い返すと 世界が提供する豊かさと比べ なんと幅の狭いものだったかと 気付きました そしてページを繰るうち 起こり始めたことが 他にもあります 少しずつですが 年の初めに用意した あの国名の長いリストが 無味乾燥で事務的な 地名の登録簿から 生き生きと息づく 実体へと変わったのです

もちろん 私は単に 1冊本を読んだだけで その国の全体像を知ることが可能だと 言おうとしているのではありません でも あの年読んだ物語が 積み重なって この素晴らしい惑星の 豊かさや多様性 複雑性に かつてなく 敏感にさせてくれたんです それはまるで 世界の数々の物語と 私がそれを読めるよう 骨折ってくれた人たちが 私にとっての世界を よりリアルなものにしてくれたかのようです 近頃では 自分の本棚を見たり 電子ブックに入っている 作品のことを考えると それが別の物語を 語っているのを感じます それは政治的、地理的、文化的、社会的、宗教的な違いを越えて 本が私たちを結び付ける力 についての物語です 人間が協同することの 可能性についての物語です

そしてそれは 私たちが生きる時代の 素晴らしさの証言です インターネットのおかげで 知らない者同士が 地球の反対側にいて 決して会うことはなくとも 物語や世界観や本といったものを 簡単に分かち合える時代です このような物語を これから先も ずっと読んでいきたいものです そしてより多くの人が 加わってくれたらと思います もし私たち皆が もっと幅広く本を読んだら 出版社は もっと翻訳出版しようと 考えるようになり それによって 皆 もっと豊かになれるでしょう

ありがとう

(拍手)

品詞分類

- 主語

- 動詞

- 助動詞

- 準動詞

- 関係詞等

TED 日本語

TED Talks

関連動画

アーティストは経済にどう貢献し、私たちは彼らをどう支えられるか?ハディ・エルデベック

2018.04.09

コンテンツを流行らせる要素とは?ダオ・グエン

2018.01.08

私がアートを制作するのは、伝統を受け継ぐタイムカプセルを作るためケイラ・ブリエット

2017.12.08

ニューヨーカー誌、象徴的な表紙イラストの舞台裏フランソワーズ・ムーリー

2017.08.17

とらえ難い心情を表す素敵な新語の数々ジョン・ケーニック

2017.03.31

2千本のおくやみ記事から学んだことラックス・ナラヤン

2017.03.23

メロドラマが教えてくれる4つの大げさな人生訓ケイト・アダムス

2017.01.03

音楽がもたらしたコンピューターの発明スティーヴン・ジョンソン

2016.12.09

Ideas worth dating -- デートする価値のあるアイデアレイン・ウィルソン

2016.10.30

購読解除の苦悩!ジェイムズ・ヴィーチ

2016.09.27

コスプレへの愛アダム・サヴェッジ

2016.08.23

「アンチ」を科学的に分類してみようネギン・ファルサド

2016.07.05

データで描く、示唆に富む肖像画ルーク・デュボワ

2016.05.19

詐欺メール 返信すると どうなるかジェイムズ・ヴィーチ

2016.02.01

日常の音に隠された思いがけない美とはメクリト・ハデロ

2015.11.10

アメリカで最も白人主義的な町々に突入!リッチ・ベンジャミン

2015.08.11

洋楽 おすすめ

RECOMMENDS

洋楽歌詞

ステイザ・キッド・ラロイ、ジャスティン・ビーバー

洋楽最新ヒット2021.08.20

スピーチレス~心の声ナオミ・スコット

洋楽最新ヒット2019.05.23

シェイプ・オブ・ユーエド・シーラン

洋楽人気動画2017.01.30

フェイデッドアラン・ウォーカー

洋楽人気動画2015.12.03

ウェイティング・フォー・ラヴアヴィーチー

洋楽人気動画2015.06.26

シー・ユー・アゲインウィズ・カリファ

洋楽人気動画2015.04.06

シュガーマルーン5

洋楽人気動画2015.01.14

シェイク・イット・オフテイラー・スウィフト

ポップス2014.08.18

オール・アバウト・ザット・ベースメーガン・トレイナー

ポップス2014.06.11

ストーリー・オブ・マイ・ライフワン・ダイレクション

洋楽人気動画2013.11.03

コール・ミー・メイビーカーリー・レイ・ジェプセン

洋楽人気動画2012.03.01

美しき生命コールドプレイ

洋楽人気動画2008.08.04

バッド・デイ~ついてない日の応援歌ダニエル・パウター

洋楽人気動画2008.05.14

サウザンド・マイルズヴァネッサ・カールトン

洋楽人気動画2008.02.19

イッツ・マイ・ライフボン・ジョヴィ

ロック2007.10.11

アイ・ウォント・イット・ザット・ウェイバックストリート・ボーイズ

洋楽人気動画2007.09.14

マイ・ハート・ウィル・ゴー・オンセリーヌ・ディオン

洋楽人気動画2007.07.12

ヒーローマライア・キャリー

洋楽人気動画2007.03.21

オールウェイズ・ラヴ・ユーホイットニー・ヒューストン

洋楽人気動画2007.02.19

オネスティビリー・ジョエル

洋楽人気動画2005.09.16