TED日本語

TED Talks(英語 日本語字幕付き動画)

TED日本語 - メクリト・ハデロ: 日常の音に隠された思いがけない美とは

TED Talks

日常の音に隠された思いがけない美とは

The unexpected beauty of everyday sounds

メクリト・ハデロ

Meklit Hadero

内容

このトークでは、シンガー・ソングライターのメクリト・ハデロが、鳥の歌声から日常会話でのピッチの上げ下げ、鍋のフタの音まで様々な例を挙げながら、静寂さえも含むあらゆる日常音が音楽であると力説します。メクリトに言わせれば、世界は音楽的表現で溢れており、私たちは既に音楽漬けになっているのです。

字幕

SCRIPT

Script

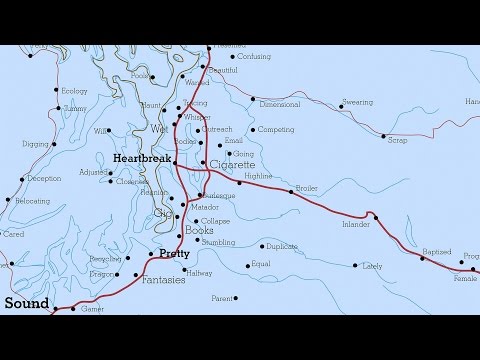

As a singer-songwriter, people often ask me about my influences or, as I like to call them, my sonic lineages. And I could easily tell you that I was shaped by the jazz and hip hop that I grew up with, by the Ethiopian heritage of my ancestors, or by the 1980s pop on my childhood radio stations. But beyond genre, there is another question: how do the sounds we hear every day influence the music that we make? I believe that everyday soundscape can be the most unexpected inspiration for songwriting, and to look at this idea a little bit more closely, I'm going to talk today about three things: nature, language and silence -- or rather, the impossibility of true silence. And through this I hope to give you a sense of a world already alive with musical expression, with each of us serving as active participants, whether we know it or not.

I'm going to start today with nature, but before we do that, let's quickly listen to this snippet of an opera singer warming up. Here it is.

(Singing)

It's beautiful, isn't it? Gotcha! That is actually not the sound of an opera singer warming up. That is the sound of a bird slowed down to a pace that the human ear mistakenly recognizes as its own. It was released as part of Peter Szoke's 1987 Hungarian recording "The Unknown Music of Birds," where he records many birds and slows down their pitches to reveal what's underneath. Let's listen to the full-speed recording.

(Bird singing)

Now, let's hear the two of them together so your brain can juxtapose them.

(Bird singing at slow then full speed)

It's incredible. Perhaps the techniques of opera singing were inspired by birdsong. As humans, we intuitively understand birds to be our musical teachers.

In Ethiopia, birds are considered an integral part of the origin of music itself. The story goes like this: 1,500 years ago, a young man was born in the Empire of Aksum, a major trading center of the ancient world. His name was Yared. When Yared was seven years old his father died, and his mother sent him to go live with an uncle, who was a priest of the Ethiopian Orthodox tradition,one of the oldest churches in the world. Now, this tradition has an enormous amount of scholarship and learning, and Yared had to study and study and study and study, and one day he was studying under a tree, when three birds came to him. One by one, these birds became his teachers. They taught him music -- scales, in fact. And Yared, eventually recognized as Saint Yared, used these scales to compose five volumes of chants and hymns for worship and celebration. And he used these scales to compose and to create an indigenous musical notation system. And these scales evolved into what is known as kinit, the unique, pentatonic, five-note, modal system that is very much alive and thriving and still evolving in Ethiopia today.

Now, I love this story because it's true at multiple levels. Saint Yared was a real, historical figure, and the natural world can be our musical teacher. And we have so many examples of this: the Pygmies of the Congo tune their instruments to the pitches of the birds in the forest around them. Musician and natural soundscape expert Bernie Krause describes how a healthy environment has animals and insects taking up low, medium and high-frequency bands, in exactly the same way as a symphony does. And countless works of music were inspired by bird and forest song. Yes, the natural world can be our cultural teacher.

So let's go now to the uniquely human world of language. Every language communicates with pitch to varying degrees, whether it's Mandarin Chinese, where a shift in melodic inflection gives the same phonetic syllable an entirely different meaning, to a language like English, where a raised pitch at the end of a sentence ... (Going up in pitch) implies a question?

(Laughter)

As an Ethiopian-American woman, I grew up around the language of Amharic, Amharina. It was my first language, the language of my parents,one of the main languages of Ethiopia. And there are a million reasons to fall in love with this language: its depth of poetics, its double entendres, its wax and gold, its humor, its proverbs that illuminate the wisdom and follies of life. But there's also this melodicism, a musicality built right in. And I find this distilled most clearly in what I like to call emphatic language -- language that's meant to highlight or underline or that springs from surprise. Take, for example, the word: "indey." Now, if there are Ethiopians in the audience, they're probably chuckling to themselves, because the word means something like "No!" or "How could he?" or "No, he didn't." It kind of depends on the situation. But when I was a kid, this was my very favorite word, and I think it's because it has a pitch. It has a melody. You can almost see the shape as it springs from someone's mouth. "Indey" -- it dips, and then raises again. And as a musician and composer, when I hear that word, something like this is floating through my mind.

(Music and singing "Indey")

(Music ends)

Or take, for example, the phrase for "It is right" or "It is correct" -- "Lickih nehu ... Lickih nehu." It's an affirmation, an agreement. "Lickih nehu." When I hear that phrase, something like this starts rolling through my mind.

(Music and singing "Lickih nehu")

(Music ends)

And in both of those cases, what I did was I took the melody and the phrasing of those words and phrases and I turned them into musical parts to use in these short compositions. And I like to write bass lines, so they both ended up kind of as bass lines.

Now, this is based on the work of Jason Moran and others who work intimately with music and language, but it's also something I've had in my head since I was a kid, how musical my parents sounded when they were speaking to each other and to us. It was from them and from Amharina that I learned that we are awash in musical expression with every word, every sentence that we speak, every word, every sentence that we receive. Perhaps you can hear it in the words I'm speaking even now.

Finally, we go to the 1950s United States and the most seminal work of 20th century avant-garde composition: John Cage's "4: 33," written for any instrument or combination of instruments. The musician or musicians are invited to walk onto the stage with a stopwatch and open the score, which was actually purchased by the Museum of Modern Art -- the score, that is. And this score has not a single note written and there is not a single note played for four minutes and 33 seconds. And, at once enraging and enrapturing, Cage shows us that even when there are no strings being plucked by fingers or hands hammering piano keys, still there is music, still there is music, still there is music. And what is this music? It was that sneeze in the back.

(Laughter)

It is the everyday soundscape that arises from the audience themselves: their coughs, their sighs, their rustles, their whispers, their sneezes, the room, the wood of the floors and the walls expanding and contracting, creaking and groaning with the heat and the cold, the pipes clanking and contributing. And controversial though it was, and even controversial though it remains, Cage's point is that there is no such thing as true silence. Even in the most silent environments, we still hear and feel the sound of our own heartbeats. The world is alive with musical expression. We are already immersed.

Now, I had my own moment of, let's say, remixing John Cage a couple of months ago when I was standing in front of the stove cooking lentils. And it was late one night and it was time to stir, so I lifted the lid off the cooking pot, and I placed it onto the kitchen counter next to me, and it started to roll back and forth making this sound.

(Sound of metal lid clanking against a counter)

And it stopped me cold. I thought, "What a weird, cool swing that cooking pan lid has." So when the lentils were ready and eaten, I hightailed it to my backyard studio, and I made this.

(Music, including the sound of the lid, and singing)

(Music ends)

Now, John Cage wasn't instructing musicians to mine the soundscape for sonic textures to turn into music. He was saying that on its own, the environment is musically generative, that it is generous, that it is fertile, that we are already immersed.

Musician, music researcher, surgeon and human hearing expert Charles Limb is a professor at Johns Hopkins University and he studies music and the brain. And he has a theory that it is possible -- it is possible -- that the human auditory system actually evolved to hear music, because it is so much more complex than it needs to be for language alone. And if that's true, it means that we're hard-wired for music, that we can find it anywhere, that there is no such thing as a musical desert, that we are permanently hanging out at the oasis, and that is marvelous. We can add to the soundtrack, but it's already playing.

And it doesn't mean don't study music. Study music, trace your sonic lineages and enjoy that exploration. But there is a kind of sonic lineage to which we all belong. So the next time you are seeking percussion inspiration, look no further than your tires, as they roll over the unusual grooves of the freeway, or the top-right burner of your stove and that strange way that it clicks as it is preparing to light. When seeking melodic inspiration, look no further than dawn and dusk avian orchestras or to the natural lilt of emphatic language. We are the audience and we are the composers and we take from these pieces we are given. We make, we make, we make, we make, knowing that when it comes to nature or language or soundscape, there is no end to the inspiration -- if we are listening.

Thank you.

(Applause)

シンガー・ソングライターをしていると よく聞かれるのが 影響を受けてきた音楽のこと 「音の血統」と呼んでいます わかりやすい答えを言えば 聴いて育った ジャズやヒップホップや 私に流れるエチオピア人の血 幼少期にラジオで流れていた 80年代ポップと言えますが でも そういうジャンルの概念を超えて 考えてみてください 私たちが毎日聞いている音が 作曲に与える影響とは? 私は 日常の音風景が 曲作りの意外なインスピレーションに なると思っています この考え方を もう少し掘り下げて 3つのテーマについてお話します 「自然」、「言語」そして「静寂」 ― 3つ目は 静寂というよりは 「完全な無音の不可能性」についてです そして皆さんには 私たちの住む世界には既に 音楽表現が息づいていることや そこで私たち一人一人が 知ってか知らずか 能動的な役目を果たしていることを 気づいていただければと思います

では 自然のお話から でも その前に 発声練習中のオペラ歌手の声を ちょっと聞いてみましょう どうぞ

(歌声開始)

(歌声終了)

美しい声ですよね 引っかかった! 実は今の オペラ歌手じゃないんです 実際は 鳥の歌声なんです モリヒバリの鳴き声の速度を 人間の耳が 人の声と間違えるまで 落としたものです 1987年ハンガリーで録音された ピーター・ソーケ作 『知られざる鳥の音楽』の一部分です この楽曲は 鳥の鳴き声を スロー再生した音を何種類も使い 隠された美を露わにしました フルスピードで聴いてみましょう

(鳥の歌声)

頭の中で並べて比べられるように 2種類を続けて聴いてみましょう

(歌声 低速版とフルスピード版)

(終了)

すごいでしょう オペラ歌唱のテクニックは 鳥の声がヒントだったのかもしれません 人は直感的に 鳥たちが 音楽の師であると知っています

エチオピアでは 鳥が音楽の起源に 欠かせない要素であると 考えられています こういう物語があります 1500年前 アクサム帝国で生まれた 若い青年の話です アクサムは大昔 商業の中心地でした 青年の名前はヤレド ヤレドが7歳のとき 父親が亡くなり 母親は 彼を叔父の元に 送りました 叔父は 世界最古の教会の一つである エチオピア正教の神父でした エチオピア正教は伝統的に 学問や教育に大いに力を入れていたので ヤレドは 死ぬほど 勉強させられることになりました ある日 木の下で勉強していると 3羽の鳥が来て 1羽1羽がそれぞれ ヤレドの師になり 音楽を ― というか音階を教えたのでした ヤレドは後に 聖人として世に知られますが この音階を使って作った 5編の聖歌と賛美歌は 礼拝や祭事に使われました ヤレドはこの音階を作曲に利用し エチオピア固有の記譜法も 考案しました この音階が クニェッツ(kinit) として知られる ― 5音音階式のモードに進化しました このスタイルは現代のエチオピアでも 今だに頻繁に使われ 進化し続けています

さて 私の大好きなこの物語 様々な面で真実だとわかります 聖ヤレドは 歴史上に 実在した人物です そして 自然界は 私達にとって 音楽の師でもあります 例をあればきりがありません コンゴのピグミー族は 楽器を 森の鳥の鳴き声に 合わせて調律します 自然の音風景の大家 音楽家バーニー・クラウスによれば 健全な環境の下では 動物や虫たちの鳴き声が 低音、中音、高音域を 構成しており これは交響楽と まったく同じなのです 鳥や森の音に影響を受けた音楽は 数え切れないほどあります そう 自然界が 人の文化の師になり得るのです

では 次に人間特有の 言語の世界を見てみましょう 程度に差はあれど どんな言語でも抑揚は重要です 中国語ならば 同じ表記の音節も 声調が変われば 全く違う意味を持ってきます 英語では 文の語尾が上がれば (語尾を上げて)質問形になりますよね?

(笑)

エチオピア系アメリカ人の私は アムハリク語を聞きながら 育ちました 両親の母語で 私が最初に憶えた言葉であり エチオピアの主要な言語の 1つです 本当にたくさんの魅力を持つ言語です 詩学性の深さや 二重の意味を持つ表現 表の意味と裏の意味 ユーモアに 人間の叡智と愚かさを描写した ことわざなど それだけじゃなく 旋律性や 音感も強く埋め込まれた言語です これが最も顕著に現れているのは 強調表現とでも呼びましょうか 何かを 明示したり強調したり 驚いたときに飛び出す表現です 例えば 「インデーィ」(indey) という単語 この中にエチオピア出身の方がいれば くすっとした方もいるのでは この単語には 状況により 「まさか!」とか 「どうして?」「ありえない!」 という意味になります 私が子供のときは この言葉が大好きでした この言葉が持つ抑揚のせいだと思います メロディーがあるからです 誰かの口から飛び出した時の 音の形が見えるくらいに 「インデーィ」(indey) すとんと落ちて 再び上昇します ミュージシャンで作曲家の私は この言葉を聞くと 頭に浮かんでくるものがあります こんな感じです

(歌と演奏)

(音楽終了)

他にも例えば 「その通り」とか 「正解」という意味の 「リッキ ノウ」(Lickih nehu) 肯定や 同意を意味します 「リッキ ノウ」(Lickih nehu) この表現を聞いたとき 頭の中で流れ出すのがこれです

(歌と演奏)

(音楽終了)

今聞いた音楽の中で 私がしたことは 両方とも 言葉の メロディーを抜き出して 音楽的パーツに変換し 小品を作曲したわけです ベースラインを考えるのが 好きなので 結局 両方そうなりました

さて これは ジェイソン・モラン達の作った 音楽と言語を密接に関連させた 作品が元になったのですが 私も実は小さい頃からずっと 思っていたことでした 両親が自分達同士や 私たち子供と話す時 音楽みたいだなと 思っていました 私は両親や アムハリク語のおかげで 私たちは音楽的表現に どっぷり浸かっていること 自分が発し 受け取る 言葉や文の一つ一つが 音楽的表現なのだということを 知ったのです 私が今こうやって話す言葉も 音楽に聞こえるのではないでしょうか

では 最後に 1950年代のアメリカ 20世紀アヴァンギャルド音楽で 最も独創的な作品 ジョン・ケージの『4:33』 この曲は 対象の楽器や その組み合わせを問いません 演奏する人やグループは ストップウォッチを持って ステージに上がり 楽譜を開きます 実はこの楽譜 ニューヨーク現代美術館が買ったんです この楽譜を です この楽譜には 音符がありません そして 4分33秒の間 奏でられる音も 一つもありません この作品は 憤りと歓喜を一度に掻き立てますが 弦が指ではじかれなくても ピアノ鍵盤が指で叩かれなくても それでも それでも それでも音楽なんだ と 伝えているのです では今この瞬間の音楽は何でしょう? 誰かが後ろでくしゃみをした音です

(笑)

観客席から生まれる 日常の音風景 咳や ため息 カサカサいう音 ひそひそ声や くしゃみ さらに部屋 床や壁の木材などが 温度の上下により 膨張し収縮し きしんだり うなったり パイプが金属音を立てて この音風景に加わります この作品は当時 そして今も 物議を醸していますが 全くの無音 などというものはない これがジョン・ケージの主張です どんなに静かな環境だとしても 自分の心臓の鼓動は聞こえるし 感じるのですから 世界は 音楽的表現に溢れ 生きており そこに私たちはもう 浸かっているのです

私自身も このジョン・ケージ的瞬間を 体験しました 数ヶ月前のことです コンロの前に立って レンズ豆を料理していました 夜遅くのことでした 混ぜないといけなかったので 鍋から蓋を取って すぐ横のカウンターに置きました すると蓋が 前後に揺れて こんな音を出したのです

(金属の蓋がガチャガチャする音)

(音終了)

私ははっとして その場で固まりました 「鍋蓋って こんなに不思議でクールな ノリが出せるのね」 そう思った私は 料理ができて 食べ終わるやいなや 裏庭にあるスタジオに直行して この曲を作りました

(鍋の蓋の音と歌の入った音楽)

(音楽終了)

さて ジョン・ケイジのねらいは 音風景の中の音の質感を意識して 作曲しろということではありませんでした ただ 私たちの日常世界は 何もしなくたって 勝手に音楽を生み出すものだし 寛容で豊穣なこの世界で 私たちは既に 音楽浸けになっているんだ ということでした

作曲家・音楽研究家かつ外科医で 人間聴覚の権威 チャールズ・リムは ジョンズ・ホプキンズ大学の教授で 音楽と脳との関係を研究しています 彼の説によれば 人間の聴覚器官は 音楽を聴くために発達した 可能性があるそうです 言語だけのための器官にしては 複雑すぎる造りをしているからです もし これが本当なら 人間という種にとって 生来音楽は欠かせないもので 人は音楽をどこにでも見つけ出すし 音の砂漠なんていうものは存在しないし 人は永久に音楽のオアシスに 居るのだということです 素晴らしいことです サウンドトラックは既に流れています 音を足すことはできますけどね

音楽を学ぶなとは言っていません 音楽を学び 自分の音の血統を辿り それを楽しんで欲しいと思います でも 私たち人間皆に共通する 音の血統もあるんです 次回 パーカッションのリズムを 考えているとき 高速道路の不規則な継ぎ目を 通り過ぎるときに ― 車のタイヤが立てる音だとか コンロの右上のバーナーが 火をつけるときに立てる ― 奇妙な音などが その答えとなります 曲の旋律を考えているときは 日没や夜明けに 鳥たちが奏でるオーケストラや 話し言葉の生き生きとした抑揚が その答えとなります 私たちは 聴衆であり 作曲家でもあるのです 自然に聞こえてくる音楽を 使えばいいわけです そして 創り出すときは 自然や 言語や 音風景が 無限のインスピレーションを 与えてくれます 私たちは 聴いてさえいればいいのです

ありがとうございました

(拍手)

品詞分類

- 主語

- 動詞

- 助動詞

- 準動詞

- 関係詞等

TED 日本語

TED Talks

関連動画

アーティストは経済にどう貢献し、私たちは彼らをどう支えられるか?ハディ・エルデベック

2018.04.09

コンテンツを流行らせる要素とは?ダオ・グエン

2018.01.08

私がアートを制作するのは、伝統を受け継ぐタイムカプセルを作るためケイラ・ブリエット

2017.12.08

ニューヨーカー誌、象徴的な表紙イラストの舞台裏フランソワーズ・ムーリー

2017.08.17

とらえ難い心情を表す素敵な新語の数々ジョン・ケーニック

2017.03.31

2千本のおくやみ記事から学んだことラックス・ナラヤン

2017.03.23

メロドラマが教えてくれる4つの大げさな人生訓ケイト・アダムス

2017.01.03

音楽がもたらしたコンピューターの発明スティーヴン・ジョンソン

2016.12.09

Ideas worth dating -- デートする価値のあるアイデアレイン・ウィルソン

2016.10.30

購読解除の苦悩!ジェイムズ・ヴィーチ

2016.09.27

コスプレへの愛アダム・サヴェッジ

2016.08.23

「アンチ」を科学的に分類してみようネギン・ファルサド

2016.07.05

データで描く、示唆に富む肖像画ルーク・デュボワ

2016.05.19

詐欺メール 返信すると どうなるかジェイムズ・ヴィーチ

2016.02.01

世界中の国の本を1冊ずつ読んでいく私の1年アン・モーガン

2015.12.21

アメリカで最も白人主義的な町々に突入!リッチ・ベンジャミン

2015.08.11

洋楽 おすすめ

RECOMMENDS

洋楽歌詞

ステイザ・キッド・ラロイ、ジャスティン・ビーバー

洋楽最新ヒット2021.08.20

スピーチレス~心の声ナオミ・スコット

洋楽最新ヒット2019.05.23

シェイプ・オブ・ユーエド・シーラン

洋楽人気動画2017.01.30

フェイデッドアラン・ウォーカー

洋楽人気動画2015.12.03

ウェイティング・フォー・ラヴアヴィーチー

洋楽人気動画2015.06.26

シー・ユー・アゲインウィズ・カリファ

洋楽人気動画2015.04.06

シュガーマルーン5

洋楽人気動画2015.01.14

シェイク・イット・オフテイラー・スウィフト

ポップス2014.08.18

オール・アバウト・ザット・ベースメーガン・トレイナー

ポップス2014.06.11

ストーリー・オブ・マイ・ライフワン・ダイレクション

洋楽人気動画2013.11.03

コール・ミー・メイビーカーリー・レイ・ジェプセン

洋楽人気動画2012.03.01

美しき生命コールドプレイ

洋楽人気動画2008.08.04

バッド・デイ~ついてない日の応援歌ダニエル・パウター

洋楽人気動画2008.05.14

サウザンド・マイルズヴァネッサ・カールトン

洋楽人気動画2008.02.19

イッツ・マイ・ライフボン・ジョヴィ

ロック2007.10.11

アイ・ウォント・イット・ザット・ウェイバックストリート・ボーイズ

洋楽人気動画2007.09.14

マイ・ハート・ウィル・ゴー・オンセリーヌ・ディオン

洋楽人気動画2007.07.12

ヒーローマライア・キャリー

洋楽人気動画2007.03.21

オールウェイズ・ラヴ・ユーホイットニー・ヒューストン

洋楽人気動画2007.02.19

オネスティビリー・ジョエル

洋楽人気動画2005.09.16