TED日本語

TED Talks(英語 日本語字幕付き動画)

TED日本語 - ルーク・サイスン: 私は如何にして心配するのを止めて「つまらない」アートを愛するようになったか

TED Talks

私は如何にして心配するのを止めて「つまらない」アートを愛するようになったか

How I learned to stop worrying and love "useless" art

ルーク・サイスン

Luke Syson

内容

ルーク・サイスンはルネサンス美術、とりわけ卓越した聖人の絵画や威厳に満ちたイタリアの貴婦人達、つまり「まじめな」アートを扱う学芸員でした。その後、職場をかえて、メトロポリタン美術館の陶磁器コレクションをまかされました。可愛らしく、飾りだらけで、「つまらない」燭台や花瓶のコレクションです。彼の趣味ではありませんでした。理解ができなかったのです。そんなある日のこと・・・(TEDxMet)

字幕

SCRIPT

Script

Two years ago, I have to say there was no problem. Two years ago, I knew exactly what an icon looked like. It looks like this. Everybody's icon, but also the default position of a curator of Italian Renaissance paintings, which I was then. And in a way, this is also another default selection. Leonardo da Vinci's exquisitely soulful image of the "Lady with an Ermine." And I use that word, soulful, deliberately. Or then there's this, or rather these: the two versions of Leonardo's "Virgin of the Rocks" that were about to come together in London for the very first time. In the exhibition that I was then in the absolute throes of organizing. I was literally up to my eyes in Leonardo, and I had been for three years. So, he was occupying every part of my brain. Leonardo had taught me, during that three years, about what a picture can do. About taking you from your own material world into a spiritual world. He said, actually, that he believed the job of the painter was to paint everything that was visible and invisible in the universe. That's a huge task. And yet, somehow he achieves it. He shows us, I think, the human soul. He shows us the capacity of ourselves to move into a spiritual realm. To see a vision of the universe that's more perfect than our own. To see God's own plan, in some sense. So this, in a sense, was really what I believed an icon was.

At about that time, I started talking to Tom Campbell,

director here of the Metropolitan Museum, about what my next move might be. The move, in fact, back to an earlier life,one I'd begun at the British Museum, back to the world of three dimensions -- of sculpture and of decorative arts -- to take over the department of European sculpture and decorative arts, here at the Met. But it was an incredibly busy time. All the conversations were done at very peculiar times of the day -- over the phone. In the end, I accepted the job without actually having been here. Again, I'd been there a couple of years before, but on that particular visit. So, it was just before the time that the Leonardo show was due to open when I finally made it back to the Met, to New York, to see my new domain. To see what European sculpture and decorative arts looked like, beyond those Renaissance collections with which I was so already familiar. And I thought, on that very first day, I better tour the galleries. Fifty-seven of these galleries -- like 57 varieties of baked beans, I believe. I walked through and I started in my comfort zone in the Italian Renaissance. And then I moved gradually around, feeling a little lost sometimes. My head, also still full of the Leonardo exhibition that was about to open, and I came across this. And I thought to myself: What the hell have I done? There was absolutely no connection in my mind at all and, in fact, if there was any emotion going on, it was a kind of repulsion. This object felt utterly and completely alien. Silly at a level that I hadn't yet understood silliness to be. And then it was made worse -- there were two of them. (Laughter) So, I started thinking about why it was, in fact, that I disliked this object so much. What was the anatomy of my distaste? Well, so much gold, so vulgar. You know, so nouveau riche, frankly. Leonardo himself had preached against the use of gold, so it was absolutely anathema at that moment. And then there's little pretty sprigs of flowers everywhere. (Laughter) And finally, that pink. That damned pink. It's such an extraordinarily artificial color. I mean, it's a color that I can't think of anything that you actually see in nature, that looks that shade. The object even has its own tutu. (Laughter) This little flouncy, spangly, bottomy bit that sits at the bottom of the vase. It reminded me, in an odd kind of way, of my niece's fifth birthday party. Where all the little girls would come either as a princess or a fairy. There was one who would come as a fairy princess. You should have seen the looks. (Laughter) And I realize that this object was in my mind, born from the same mind, from the same womb, practically, as Barbie Ballerina. (Laughter) And then there's the elephants. (Laughter) Those extraordinary elephants with their little, sort of strange, sinister expressions and Greta Garbo eyelashes, with these golden tusks and so on. I realized this was an elephant that had absolutely nothing to do with a majestic march across the Serengeti. It was a Dumbo nightmare. (Laughter)

But something more profound was happening as well. These objects, it seemed to me, were quintessentially the kind that I and my liberal left friends in London had always seen as summing up something deplorable about the French aristocracy in the 18th century. The label had told me that these pieces were made by the Sevres Manufactory, made of porcelain in the late 1750s, and designed by a designer called Jean-Claude Duplessis, actually somebody of extraordinary distinction as I later learned. But for me, they summed up a kind of, that sort of sheer uselessness of the aristocracy in the 18th century. I and my colleagues had always thought that these objects, in way, summed up the idea of, you know -- no wonder there was a revolution. Or, indeed, thank God there was a revolution. There was a sort of idea really, that, if you owned a vase like this, then there was really only one fate possible. (Laughter)

So, there I was -- in a sort of paroxysm of horror. But I took the job and I went on looking at these vases. I sort of had to because they're on a through route in the Met. So, almost anywhere I went, there they were. They had this kind of odd sort of fascination, like a car accident. Where I couldn't stop looking. And as I did so, I started thinking: Well, what are we actually looking at here? And what I started with was understanding this as really a supreme piece of design. It took me a little time. But, that tutu for example -- actually, this is a piece that does dance in its own way. It has an extraordinary lightness and yet, it is also amazing balanced. It has these kinds of sculptural ingredients. And then the play between -- actually really quite carefully disposed color and gilding, and the sculptural surface, is really rather remarkable. And then I realized that this piece went into the kiln four times, at least four times in order to arrive at this. How many moments for accident can you think of that could have happened to this piece? And then remember, not just one, but two. So he's having to arrive at two exactly matched vases of this kind. And then this question of uselessness. Well actually, the end of the trunks were originally candle holders. So what you would have had were candles on either side. Imagine that effect of candlelight on that surface. On the slightly uneven pink, on the beautiful gold. It would have glittered in an interior, a little like a little firework.

And at that point, actually, a firework went off in my brain. Somebody reminded me that, that word 'fancy' -- which in a sense for me, encapsulated this object -- actually comes from the same root as the word 'fantasy.' And that what this object was just as much in a way, in its own way, as a Leonardo da Vinci painting, is a portal to somewhere else. This is an object of the imagination. If you think about the mad 18th-century operas of the time -- set in the Orient. If you think about divans and perhaps even opium-induced visions of pink elephants, then at that point, this object starts to make sense. This is an object which is all about escapism. It's about an escapism that happens -- that the aristocracy in France sought very deliberately to distinguish themselves from ordinary people.

It's not an escapism that we feel particularly happy with today, however. And again, going on thinking about this, I realize that in a way we're all victims of a certain kind of tyranny of the triumph of modernism whereby form and function in an object have to follow one another, or are deemed to do so. And the extraneous ornament is seen as really, essentially, criminal. It's a triumph, in a way, of bourgeois values rather than aristocratic ones. And that seems fine. Except for the fact that it becomes a kind of sequestration of imagination. So just as in the 20th century, so many people had the idea that their faith took place on the Sabbath day, and the rest of their lives -- their lives of washing machines and orthodontics -- took place on another day. Then, I think we've started doing the same. We've allowed ourselves to lead our fantasy lives in front of screens. In the dark of the cinema, with the television in the corner of the room. We've eliminated, in a sense, that constant of the imagination that these vases represented in people's lives. So maybe it's time we got this back a little. I think it's beginning to happen. In London, for example, with these extraordinary buildings that have been appearing over the last few years. Redolent, in a sense, of science fiction, turning London into a kind of fantasy playground. It's actually amazing to look out of a high building nowadays there. But even then, there's a resistance. London has called these buildings the Gherkin, the Shard, the Walkie Talkie -- bringing these soaring buildings down to Earth. There's an idea that we don't want these anxious-making, imaginative journeys to happen in our daily lives. I feel lucky in a way, I've encountered this object. (Laughter) I found him on the Internet when I was looking up a reference. And there he was. And unlike the pink elephant vase, this was a kind of love at first sight. In fact, reader, I married him. I bought him. And he now adorns my office. He's a Staffordshire figure made in the middle of the 19th century. He represents the actor, Edmund Kean, playing Shakespeare's Richard III. And it's based, actually, on a more elevated piece of porcelain. So I loved, on an art historical level, I loved that layered quality that he has. But more than that, I love him. In a way that I think would have been impossible without the pink Sevres vase in my Leonardo days. I love his orange and pink breeches. I love the fact that he seems to be going off to war, having just finished the washing up. (Laughter) He seems also to have forgotten his sword. I love his pink little cheeks, his munchkin energy. In a way, he's become my sort of alter ego. He's, I hope, a little bit dignified, but mostly rather vulgar. (Laughter) And energetic, I hope, too. I let him into my life because the Sevres pink elephant vase allowed me to do so. And before that Leonardo, I understood that this object could become part of a journey for me every day, sitting in my office. I really hope that others, all of you, visiting objects in the museum, and taking them home and finding them for yourselves, will allow those objects to flourish in your imaginative lives. Thank you very much. (Applause)

2年前までは何の問題も ありませんでした 「イコン」がどんな姿をしているか わかっていたからです これこそイコンの姿です 皆さんもそうでしょうが イタリア・ルネサンス絵画の 学芸員だった私にとって 標準的なイコンです または こちらも標準的でしょう レオナルド・ダ・ヴィンチが 魂を込めた優美な作品 ― 『白貂を抱く貴婦人』です あえて「魂を込めた」と言いましょう さらに この作品 ― 2点の『岩窟の聖母』です ロンドンで初めて2点同時に 展示される直前のことでした この展覧会の準備は 本当に大変でした 私は文字通り レオナルドに没頭して 3年間 過ごしていたのです だからレオナルドの事で 頭の隅々まで一杯でした その3年間で彼から学んだのは 絵画の可能性 すなわち 日常の物質界から 精神世界に 人を導くことです 見えないものも含めた 宇宙の全てを描くのが 画家の仕事であると レオナルドは言っています 彼は その偉業を なんとか成し遂げたのです 彼が表現するもの それは 人間の魂であり 魂の領域に達することができる能力 ― より完ぺきな宇宙を想像できる能力 ― または神の真意を知る能力と 言ってもいいでしょう だから それが 私が信ずるイコンでした

その頃 私は転職先について

メトロポリタン美術館長の トム・キャンベルに 相談を持ちかけました その内容とは私がキャリアの初期に 大英博物館で取り組んだ ― 三次元の世界 すなわち 彫刻と装飾芸術の世界に回帰して メトロポリタンのヨーロッパ彫刻・ 装飾芸術部門を引き継ぐことでした ただ かなり忙しい時期で 話は電話で しかも妙な時間にしか できませんでした 結局 一度も訪問せずに 仕事を引き受けました 数年前に訪れる機会はありましたが 別の用事でした だからレオナルド展が始まる 直前にやっと ニューヨーク メトロポリタン美術館で それまで親しんできた ― ルネサンスの作品を離れ 新しい職場である ― ヨーロッパ彫刻・装飾芸術部門の 様子を見ることができました 初日にギャラリーを 見て回ろうと思いました 57室もあります 豆の缶詰のようで 見分けがつきません 一番落ち着くイタリア・ルネサンスの エリアから始めて 順に見ていきましたが 時々 迷ったかと思いました 開幕直前のレオナルド展で 頭が一杯だった私が 目にしたのが これです その時 思いました 「やっちまった!」 私の心に響くものはゼロで 感情が湧いたとしても 一種の嫌悪感だけでした このオブジェは ひどく異様に見えました 馬鹿げているにも 程があります しかも さらに悪いことに 同じものが2つもあったのです (笑) それで私は このオブジェが なぜそんなに嫌なのかを 分析するようになりました この嫌悪感は どこから来るのだろうか? まず 金を使いすぎていて 俗っぽい・・・ はっきり言って成金趣味です レオナルドは 金の使用を戒めていたので 当時の私には 絶対的なタブーだったのです さらに 可愛らしい花の装飾が 散りばめられています (笑) そして この忌々しいピンク・・・ 極めて人工的な色彩です 自然の中で 実際に目にするものには こんな色合いは ないはずです このオブジェには チュチュまでついています (笑) けばけばしい派手な足が 花瓶の底についています これを見て思い出したのが 姪の5才の誕生パーティーです 女の子が全員 お姫様か 妖精に扮してやって来たのです 妖精のお姫様までいました 見ものでしたよ (笑) それで気づいたのです このオブジェと 同じ精神 同じ胎内から 生まれたのが バレリーナのバービー人形です (笑) そして このゾウです (笑) この風変わりなゾウは 少し奇妙で意地悪な顔つきをしていて グレタ・ガルボ風のまつ毛と 金の牙なんかが ついています これはセレンゲティ国立公園で 堂々と歩む象とは 似ても似つきません まるで悪夢に出てくるダンボです (笑)

一方で もっと重要なこともありました これらのオブジェは 私や ロンドンにいる リベラル左派の友人達にとって 18世紀 フランス貴族の みじめさそのものを 体現しているように 見えたのです ラベルを見ると この作品は 1750年代の後半に 国立セーヴル陶磁器製作所で 作られた磁器で ジャン=クロード・デュプレシが デザインしました 後に知ったのですが とても優れた芸術家でした でも私には この作品が 18世紀の貴族社会が ひどくつまらないものだった ということを 端的に表しているように 思えました 私も同僚も いつも こう考えていました このオブジェを見れば 革命が起こるのも もっともな話だ それどころか 「革命万歳」とさえ思いました こんな花瓶を持っていたら 待ち受けるのは こんな運命に決まっています (笑)

私は その場所で ひどい嫌悪感を感じていました でも仕事を引き受けてから この花瓶を見続けました 館内を巡るには そこを通るしかなかったのです 私がどこへ行くにも その前を通ります 不可思議な魅力があって 交通事故に目を奪われるのに 似ていました 目を背けられないのです そのうち こう思い始めました このオブジェの 正体は何だろうか? それで まず この作品のデザインが 傑作だと 考えようとしました 多少 時間はかかりました ただ チュチュを見ても 独特の躍動感があります とても軽やかでありながら 驚くべき均衡を保っています この作品には そんな 彫刻的要素があるのです さらに 細心の注意を払って 配置された色彩や塗金と 彫刻の表面が織りなす効果は 本当に見事です また この作品を 仕上げるには 最低4回は窯に入れる 必要があるそうです 完成までに 失敗につながる場面が 何度もあったはずです しかも それが1点だけでなく 2点もあるのです 職人は全く同じ花瓶を 2つも作らなければ ならなかったのです それに これは 役に立たないのでしょうか 元々ゾウの鼻先は ロウソク立てになっていました 両側にロウソクが 立てられていたのでしょう 花瓶に映る 光の効果を想像してください 少し濃淡のあるピンクと 美しい金への効果・・・ きっと室内できらめいて 小さな花火のようだったでしょう

その瞬間 私の頭の中でも 花火が鳴りました このオブジェが体現している ― “fancy” つまり幻想という言葉は ファンタジーと語源が同じだそうです そして このオブジェは 別世界への入り口だという点で ダ・ヴィンチの絵画と 全く同じなのです これは想像の産物です 18世紀の東洋が舞台の 愉快なオペラや アヘン窟やピンクの象の幻影を 思い浮かべた瞬間に このオブジェが 理解できるようになります これはまさに現実から 逃れるためのオブジェです テーマは現実逃避なのです フランス貴族は 自分たちを大衆と区別するために 意図的に現実逃避しようとしました

ただ それは現代の感性に 合うものではありません さらに突き詰めて考えると 私達は皆 モダニズムの勝利に 支配された犠牲者だと 思うようになりました モダニズムでは 形は機能に ― 機能は形に 従うよう定められています うわべだけの装飾は 絶対的な罪とされます 貴族的というより ブルジョワ的価値の勝利です 悪い事ではなさそうですが 想像力が奪われる ことだけは問題です 20世紀と同じように こう考える人が多かったのです 信仰は 安息日だけに生じるもの ― 残りの日には 洗濯したり 歯を矯正したりといった 日常生活が続くという考え方です 現代の私達も同じだと思います 空想が許されるのは スクリーンの前だけ ― 映画館の闇の中や テレビの前だけなのです 私達は これらの花瓶が 日常生活の中で表していた ― 常に身の回りにある想像力を 取り除いてきたのです そろそろ想像力を 取り戻す時かもしれません 想像力の回復は始まりつつあります 例えばロンドンでは ご覧のように ここ数年で 面白い建造物が現れてきました SFを思わせる建物が ロンドンを 空想の遊び場に変えています 高層ビルからの眺めは最高ですが 反対派もいます 「ガーキン(ピクルス)」「ザ・シャード (破片)」「ウォーキートーキー」と あだ名で呼んで 俗世に引きずり下ろそうとします 想像力の旅は 不安をかき立てるから 日常生活には 不要だという考え方です でも私は このオブジェに出会えて よかったと思っています (笑) 「彼」を見つけたのは ネットで調べ物をしている時でした その時 彼がいたのです ピンクの象の花瓶とは違って 一目惚れして 結局 結婚しました 購入したのです 今は私のオフィスを飾っています 19世紀中頃の スタッフォードシャー製です シェイクスピアのリチャード三世を 演じるエドマンド・キーンです 実は高級な磁器のコピーです 私は美術史のレベルで 彼が持っている 多層性が気に入りました でもそれ以上に 彼を愛しています あの時 ピンクのセーヴル花瓶に 出会わなければ あり得なかったことです 彼のオレンジとピンクの ズボンは素敵です 身なりを整えてから 戦に出かけるように 見える所も好きです (笑) 剣のことさえ 忘れているみたいです 赤い頬は元気がある証拠です ある意味では 彼は私の分身です ほんの少し威厳がありますが 総じて俗っぽいですね (笑) それに活気に満ちています 私もそうありたいです セーヴルのピンクの花瓶のおかげで 彼が私の日常に入ってきました そしてレオナルドよりも このオブジェの方が オフィスでじっとしている私には 想像という旅の 伴侶にふさわしいのです 皆さんも美術館に オブジェを見に来たり 家に持ち帰ったり 自分で発見したりすることで ぜひ想像豊かな 生活を送ってください ありがとうございました (拍手)

品詞分類

- 主語

- 動詞

- 助動詞

- 準動詞

- 関係詞等

TED 日本語

TED Talks

関連動画

失うことで不完全さの中に美を見出した芸術家アリッサ・モンクス

2016.11.17

前から見たかった全ての芸術作品を手元に、そして検索可能にアミット・スード

2016.06.29

儚くも美しき地球の絵画ザリア・フォーマン

2016.06.17

誰も聞いたことのない、システィーナ礼拝堂の物語エリザベス・レヴ

2016.02.12

アーティストの心の中を旅するダスティン・イェリン

2015.09.15

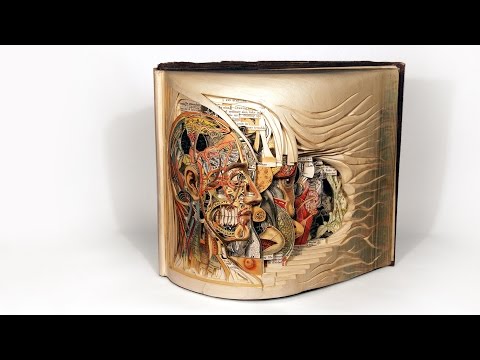

古びた本が繊細なアートに生まれ変わる時ブライアン・デットマー

2015.02.06

絵画に秘められた生命マウリツィオ・セラチーニ

2012.10.12

美術館の展示室で物語をつむぐトーマス・P・キャンベル

2012.10.05

彫刻になった空間 ― 我々の内部空間と、我々なしで存在する空間アントニー・ゴームリー

2012.09.07

絵画に見つける物語トレイシー・シュヴァリエ

2012.07.25

Webに作る美術館の美術館アミット・スード

2011.05.16

画家と振り子トム・シャノン

2010.02.05

重力抵抗彫刻トム・シャノン

2009.05.06

洋楽 おすすめ

RECOMMENDS

洋楽歌詞

ダイナマイトビーティーエス

洋楽最新ヒット2020.08.20

ディス・イズ・ミーグレイテスト・ショーマン・キャスト

洋楽人気動画2018.01.11

グッド・ライフGイージー、ケラーニ

洋楽人気動画2017.01.27

ホワット・ドゥ・ユー・ミーン?ジャスティン・ビーバー

洋楽人気動画2015.08.28

ファイト・ソングレイチェル・プラッテン

洋楽人気動画2015.05.19

ラヴ・ミー・ライク・ユー・ドゥエリー・ゴールディング

洋楽人気動画2015.01.22

アップタウン・ファンクブルーノ・マーズ、マーク・ロンソン

洋楽人気動画2014.11.20

ブレイク・フリーアリアナ・グランデ

洋楽人気動画2014.08.12

ハッピーファレル・ウィリアムス

ポップス2014.01.08

カウンティング・スターズワンリパブリック

ロック2013.05.31

ア・サウザンド・イヤーズクリスティーナ・ペリー

洋楽人気動画2011.10.26

ユー・レイズ・ミー・アップケルティック・ウーマン

洋楽人気動画2008.05.30

ルーズ・ユアセルフエミネム

洋楽人気動画2008.02.21

ドント・ノー・ホワイノラ・ジョーンズ

洋楽人気動画2008.02.15

オンリー・タイムエンヤ

洋楽人気動画2007.10.03

ミス・ア・シングエアロスミス

ロック2007.08.18

タイム・トゥ・セイ・グッバイサラ・ブライトマン

洋楽人気動画2007.06.08

シェイプ・オブ・マイ・ハートスティング

洋楽人気動画2007.03.18

ウィ・アー・ザ・ワールド(U.S.A. フォー・アフリカ)マイケル・ジャクソン

洋楽人気動画2006.05.14

ホテル・カリフォルニアイーグルス

ロック2005.07.06