TED日本語

TED Talks(英語 日本語字幕付き動画)

TED日本語 - ボブ・マンコフ: 「ニューヨーカー」のマンガの分析

TED Talks

「ニューヨーカー」のマンガの分析

Anatomy of a New Yorker cartoon

ボブ・マンコフ

Bob Mankoff

内容

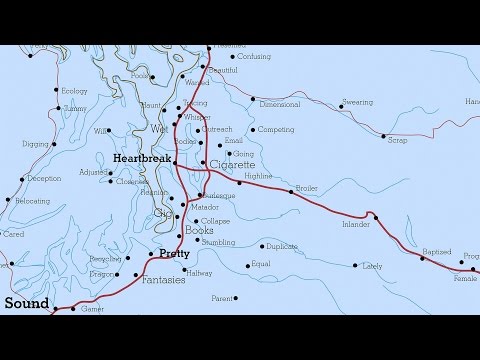

「ニューヨーカー」の編集部には毎週1000通のマンガが舞いこみます。その中から採用されるのは17枚ほどしかありません。この爆笑ものの、テンポのよい、深い洞察に満ちた講演で、この雑誌で長年マンガエディターを務める自称「ユーモアアナリスト」のボブ・マンコフが「ニューヨーカー」の「アイデア図」に描かれる笑いを解剖し、何がおもしろく何がそうでないのか、その理由を話します。

字幕

SCRIPT

Script

I'm going to be talking about designing humor, which is sort of an interesting thing, but it goes to some of the discussions about constraints, and how in certain contexts, humor is right, and in other contexts it's wrong.

Now, I'm from New York, so it's 100 percent satisfaction here. Actually, that's ridiculous, because when it comes to humor,75 percent is really absolutely the best you can hope for. Nobody is ever satisfied 100 percent with humor except this woman.

Bob Mankoff: That's my first wife. (Laughter) That part of the relationship went fine. (Laughter)

Now let's look at this cartoon. One of the things I'm pointing out is that cartoons appear within the context of The New Yorker magazine, that lovely Caslon type, and it seems like a fairly benign cartoon within this context. It's making a little bit fun of getting older, and, you know, people might like it.

But like I said, you can not satisfy everyone. You couldn't satisfy this guy.

"Another joke on old white males. Ha ha. The wit. It's nice, I'm sure to be young and rude, but some day you'll be old, unless you drop dead as I wish."

(Laughter)

The New Yorker is rather a sensitive environment, very easy for people to get their nose out of joint. And one of the things that you realize is it's an unusual environment. Here I'm one person talking to you. You're all collective. You all hear each other laugh and know each other laugh. In The New Yorker, it goes out to a wide audience, and when you actually look at that, and nobody knows what anybody else is laughing at, and when you look at that the subjectivity involved in humor is really interesting.

"Discouraging data on the antidepressant."

(Laughter)

Indeed, it is discouraging. Now, you would think, well, look, most of you laughed at that. Right? You thought it was funny. In general, that seems like a funny cartoon, but let's look what online survey I did. Generally, about 85 percent of the people liked it. A hundred and nine voted it a 10, the highest. Ten voted it one. But look at the individual responses.

"I like animals!!!!!" Look how much they like them. (Laughter) "I don't want to hurt them. That doesn't seem very funny to me."

This person rated it a two. "I don't like to see animals suffer -- even in cartoons."

To people like this, I point out we use anesthetic ink. Other people thought it was funny. That actually is the true nature of the distribution of humor when you don't have the contagion of humor.

Humor is a type of entertainment. All entertainment contains a little frisson of danger, something that might happen wrong, and yet we like it when there's protection. That's what a zoo is. It's danger. The tiger is there. The bars protect us. That's sort of fun, right? That's a bad zoo. (Laughter) It's a very politically correct zoo, but it's a bad zoo. But this is a worse one. (Laughter) So in dealing with humor in the context of The New Yorker, you have to see, where is that tiger going to be? Where is the danger going to exist? How are you going to manage it? My job is to look at 1,000 cartoons a week. But The New Yorker only can take 16 or 17 cartoons, and we have 1,000 cartoons. Of course, many, many cartoons must be rejected. Now, we could fit more cartoons in the magazine if we removed the articles. (Laughter) But I feel that would be a huge loss,one I could live with, but still huge.

Cartoonists come in through the magazine every week. The average cartoonist who stays with the magazine does 10 or 15 ideas every week. But they mostly are going to be rejected. That's the nature of any creative activity. Many of them fade away. Some of them stay.

Matt Diffee is one of them. Here's one of his cartoons. (Laughter)

Drew Dernavich. "Accounting night at the improv." "Now is the part of the show when we ask the audience to shout out some random numbers."

Paul Noth. "He's all right. I just wish he were a little more pro-Israel." (Laughter)

Now I know all about rejection, because when I quit -- actually, I was booted out of -- psychology school and decided to become a cartoonist, a natural segue, from 1974 to 1977 I submitted 2,000 cartoons to The New Yorker, and got 2,000 cartoons rejected by The New Yorker. At a certain point, this rejection slip, in 1977 -- [ We regret that we are unable to use the enclosed material. Thank you for giving us the opportunity to consider it. ] - magically changed to this. [ Hey! You sold one. No shit! You really sold a cartoon to the fucking New Yorker magazine. ] (Laughter) Now of course that's not what happened, but that's the emotional truth. And of course, that is not New Yorker humor.

What is New Yorker humor? Well, after 1977, I broke into The New Yorker and started selling cartoons. Finally, in 1980, I received the revered New Yorker contract, which I blurred out parts because it's none of your business.

From 1980. "Dear Mr. Mankoff, confirming the agreement there of -- "blah blah blah blah -- blur -- "for any idea drawings."

With respect to idea drawings, nowhere in the contract is the word "cartoon" mentioned. The word "idea drawings," and that's the sine qua non of New Yorker cartoons. So what is an idea drawing? An idea drawing is something that requires you to think. Now that's not a cartoon. It requires thinking on the part of the cartoonist and thinking on your part to make it into a cartoon. (Laughter)

Here are some, generally you get my cast of cartoon mind.

"There is no justice in the world. There is some justice in the world. The world is just."

This is What Lemmings Believe.

(Laughter)

The New Yorker and I, when we made comments, the cartoon carries a certain ambiguity about what it actually is. What is it, the cartoon? Is it really about lemmings? No. It's about us. You know, it's my view basically about religion, that the real conflict and all the fights between religion is who has the best imaginary friend. (Laughter)

And this is my most well-known cartoon. "No, Thursday's out. How about never - is never good for you?" It's been reprinted thousands of times, totally ripped off. It's even on thongs, but compressed to "How about never - is never good for you?"

Now these look like very different forms of humor but actually they bear a great similarity. In each instance, our expectations are defied. In each instance, the narrative gets switched. There's an incongruity and a contrast. In "No, Thursday's out. How about never - is never good for you?" what you have is the syntax of politeness and the message of being rude. That really is how humor works. It's a cognitive synergy where we mash up these two things which don't go together and temporarily in our minds exist. He is both being polite and rude. In here, you have the propriety of The New Yorker and the vulgarity of the language. Basically, that's the way humor works.

So I'm a humor analyst, you would say. Now E.B. White said, analyzing humor is like dissecting a frog. Nobody is much interested, and the frog dies. Well, I'm going to kill a few, but there won't be any genocide. But really, it makes me - Let's look at this picture. This is an interesting picture, The Laughing Audience. There are the people, fops up there, but everybody is laughing, everybody is laughing except one guy. This guy. Who is he? He's the critic. He's the critic of humor, and really I'm forced to be in that position, when I'm at The New Yorker, and that's the danger that I will become this guy.

Now here's a little video made by Matt Diffee, sort of how they imagine if we really exaggerated that.

(Video) Bob Mankoff: "Oooh, no. Ehhh. Oooh. Hmm. Too funny. Normally I would but I'm in a pissy mood. I'll enjoy it on my own. Perhaps. No. Nah. No. Overdrawn. Underdrawn. Drawn just right, still not funny enough. No. No. For God's sake no, a thousand times no.

(Music)

No. No. No. No. No. [ Four hours later ] Hey, that's good, yeah, whatcha got there?

Office worker: Got a ham and swiss on rye? BM: No.

Office worker: Okay. Pastrami on sourdough? BM: No.

Office worker: Smoked turkey with bacon? BM: No.

Office worker: Falafel? BM: Let me look at it. Eh, no. Office worker: Grilled cheese? BM: No. Office worker: BLT? BM: No.

Office worker: Black forest ham and mozzarella with apple mustard? BM: No.

Office worker: Green bean salad? BM: No.

(Music)

No. No. Definitely no. [ Several hours after lunch ]

(Siren)

No. Get out of here.

(Laughter)

That's sort of an exaggeration of what I do.

Now, we do reject, many, many, many cartoons, so many that there are many books called "The Rejection Collection." "The Rejection Collection" is not quite New Yorker kind of humor. And you might notice the bum on the sidewalk here who is boozing and his ventriloquist dummy is puking. See, that's probably not going to be New Yorker humor. It's actually put together by Matt Diffee,one of our cartoonists.

So I'll give you some examples of rejection collection humor.

"I'm thinking about having a child."

(Laughter)

There you have an interesting -- the guilty laugh, the laugh against your better judgment.

(Laughter)

"Ass-head. Please help."

(Laughter)

Now, in fact, within a context of this book, which says, "Cartoons you never saw and never will see in The New Yorker," this humor is perfect. I'm going to explain why. There's a concept about humor about it being a benign violation. In other words, for something to be funny, we've got to think it's both wrong and also okay at the same time. If we think it's completely wrong, we say, "That's not funny." And if it's completely okay, what's the joke? Okay? And so, this benign, that's true of "No, Thursday's out. How about never - is never good for you?" It's rude. The world really shouldn't be that way. Within that context, we feel it's okay. So within this context, "Asshead. Please help" is a benign violation.

Within the context of The New Yorker magazine ... "T-Cell Army: Can the body's immune response help treat cancer?" Oh, goodness. You're reading about this smart stuff, this intelligent dissection of the immune system. You glance over at this, and it says, "Asshead. Please help"? God. So there the violation is malign. It doesn't work. There is no such thing as funny in and of itself. Everything will be within the context and our expectations.

One way to look at it is this. It's sort of called a meta-motivational theory about how we look, a theory about motivation and the mood we're in and how the mood we're in determines the things we like or dislike. When we're in a playful mood, we want excitement. We want high arousal. We feel excited then. If we're in a purposeful mood, that makes us anxious. "The Rejection Collection" is absolutely in this field. You want to be stimulated. You want to be aroused. You want to be transgressed. It's like this, like an amusement park.

He laughs. He is both in danger and safe, incredibly aroused. There's no joke. No joke needed. If you arouse people enough and get them stimulated enough, they will laugh at very, very little.

This is another cartoon from "The Rejection Collection." "Too snug?" That's a cartoon about terrorism. The New Yorker occupies a very different space. It's a space that is playful in its own way, and also purposeful, and in that space, the cartoons are different.

Now I'm going to show you cartoons The New Yorker did right after 9/11, a very, very sensitive area when humor could be used. How would The New Yorker attack it? It would not be with a guy with a bomb saying, "Too snug?" Or there was another cartoon I didn't show because actually I thought maybe people would be offended. The great Sam Gross cartoon, this happened after the Muhammad controversy where it's Muhammad in heaven, the suicide bomber is all in little pieces, and he's saying to the suicide bomber, "You'll get the virgins when we find your penis."

(Laughter)

Better left undrawn.

The first week we did no cartoons. That was a black hole for humor, and correctly so. It's not always appropriate every time. But the next week, this was the first cartoon.

"I thought I'd never laugh again. Then I saw your jacket."

It basically was about, if we were alive, we were going to laugh. We were going to breathe. We were going to exist. Here's another one.

"I figure if I don't have that third martini, then the terrorists win."

These cartoons are not about them. They're about us. The humor reflects back on us. The easiest thing to do with humor, and it's perfectly legitimate, is a friend makes fun of an enemy. It's called dispositional humor. It's 95 percent of the humor. It's not our humor.

Here's another cartoon.

"I wouldn't mind living in a fundamentalist Islamic state."

(Laughter)

Humor does need a target. But interestingly, in The New Yorker, the target is us. The target is the readership and the people who do it. The humor is self-reflective and makes us think about our assumptions. Look at this cartoon by Roz Chast, the guy reading the obituary.

"Two years younger than you,12 years older than you,three years your junior, your age on the dot, exactly your age."

That is a deeply profound cartoon. And so The New Yorker is also trying to, in some way, make cartoons say something besides funny and something about us. Here's another one.

"I started my vegetarianism for health reasons, Then it became a moral choice, and now it's just to annoy people."

(Laughter)

"Excuse me - I think there's something wrong with this in a tiny way that no one other than me would ever be able to pinpoint."

So it focuses on our obsessions, our narcissism, our foils and our foibles, really not someone else's.

The New Yorker demands some cognitive work on your part, and what it demands is what Arthur Koestler, who wrote "The Act of Creation" about the relationship between humor, art and science, is what's called bisociation. You have to bring together ideas from different frames of reference, and you have to do it quickly to understand the cartoon. If the different frames of reference don't come together in about .5 seconds, it's not funny, but I think they will for you here. Different frames of reference.

"You slept with her, didn't you?"

(Laughter)

"Lassie! Get help!!"

(Laughter)

It's called French Army Knife.

(Laughter)

And this is Einstein in bed. "To you it was fast."

(Laughter)

Now there are some cartoons that are puzzling. Like, this cartoon would puzzle many people. How many people know what this cartoon means? The dog is signaling he wants to go for a walk. This is the signal for a catcher to walk the dog. That's why we run a feature in the cartoon issue every year called "I Don't Get It: The New Yorker Cartoon I.Q. Test." (Laughter)

The other thing The New Yorker plays around with is incongruity, and incongruity, I've shown you, is sort of the basis of humor. Something that's completely normal or logical isn't going to be funny. But the way incongruity works is, observational humor is humor within the realm of reality.

"My boss is always telling me what to do." Okay? That could happen. It's humor within the realm of reality.

Here, cowboy to a cow: "Very impressive. I'd like to find 5,000 more like you."

We understand that. It's absurd. But we're putting the two together.

"Damn it, Hopkins, didn't you get yesterday's memo?"

Now that's a little puzzling, right? It doesn't quite come together. In general, people who enjoy more nonsense, enjoy more abstract art, they tend to be liberal, less conservative, that type of stuff. But for us, and for me, helping design the humor, it doesn't make any sense to compare one to the other. It's sort of a smorgasbord that's made all interesting.

So I want to sum all this up with a caption to a cartoon, and I think this sums up the whole thing, really, about The New Yorker cartoons.

"It sort of makes you stop and think, doesn't it."

(Laughter)

And now, when you look at New Yorker cartoons, I'd like you to stop and think a little bit more about them.

Thank you.

これからユーモアのつくり方についてお話ししましょう これは興味深いことですが それに関わる制約や なぜユーモアが状況によって笑えたり 笑えないかについてもお話しします

さて 私はニューヨークの人間なので これは100%面白い でも 実際ありえないことですユーモアというものは 75%も面白いと言えば最高といったところだからです 100%ユーモアに満足する人などいません この人以外は

(笑い声)

最初の妻です (笑) この辺りは 二人うまくいったのですがね (笑)

さて このマンガを見てみましょう ここで 重要なのは これらのマンガは『ニューヨーカー』のページ上で 読者の目に入るということです このエレガントな書体に囲まれて このページ上では特に問題もないマンガに思えます 老いることを少々からかったもので 大方皆が楽しめるものでしょう

しかし 先ほど言ったように全員を満足させるのは無理です この男性はだめでした

「また老人ネタのジョークか笑えるね 年寄りを馬鹿にして楽しいだろう でも 君だっていつか歳をとるんだ 途中で死ななければいいけどね

(笑)

『ニューヨーカー』では気をつけないと 簡単に読者の気分を損ねることになります お分かりいただけると思いますが これは特殊な環境なんです 今 ここでは皆さんは私の話を聞いて 集団ですから 周りの笑い声から皆笑っているのが分かります 『ニューヨーカー』の場合雑誌は様々な読者の手に渡り ひとりで読んでいても 他の誰が何を見て笑っているかわかりません それを考えるとユーモア解釈に関わる読者の主観が 実に興味深いものになります

こちらのマンガを見てみましょう

「抗ウツ剤についての悲しいデータ」

(笑)

本当にこれは悲しいことです さて この会場では これを見て ほとんど全員が笑っていますね 皆 面白いと感じたわけです 一般的には これは笑えるマンガです でも オンライン調査の結果を見てみましょう 面白いと答えたのは全体の約85% 109人が最高評価の10を10人が1をつけました ただ個々の反応を見てください

「動物大好き!!!!!」 この動物への愛情を見てください (笑) 「動物を虐待したくないこれは面白いとは思えない」

この人は2をつけました 「動物が苦しむのは見たくない―たとえマンガであっても」

このような人には 麻酔インクで印刷していると伝えます 他の人々はこれを面白いと思いました これがユーモアの分布の本質で ユーモアがうまく拡散しないときにはこうなります

ユーモアは一種の娯楽です あらゆる娯楽にはちょっとしたスリルが伴います 何か良くないことが起こるかもしれない それでも安全策があれば楽しめます 動物園も同じです 危険ですトラがすぐそこにいるのです 檻があるから 安心して楽しめますね? こんな動物園はつまらない (笑) 動物愛好家には良い動物園ですが行ってもおもしろくありません でも これはもっとひどい (笑) 『ニューヨーカー』の環境でユーモアを扱う時 トラをどこに置くか考える必要があります 危険をどこに仕組み どうやってコントロールするか? 私の仕事は毎週1000枚のマンガを審査することです 『ニューヨーカー』に載せられるのは16枚か17枚 でも 全部で1000もあるのです もちろん沢山のマンガをボツにしなくてはなりません 雑誌から記事を減らしたら もっとマンガを載せられるのですが (笑) しかし それは大きな損失になるでしょう 耐えられはしますが 大きな損失です

毎週 新しい漫画家が作品を送ってきます 本誌に投稿を続ける漫画家は 週に10から15のアイデアを送ってきますが そのほとんどがボツになります それが創造活動というものです 多くの人が去り 一部が残ります

マット・ディフィーはその一人です これは彼の作品です (笑)

ドリュー・ダーナビッチ「会計士の即興コメディー」 「さあ ここで聴衆のみなさんには 適当な数字を叫んでもらいましょう」

ポール・ノス「彼は良さそうだもう少しイスラエル寄りなら良いのだが」 (笑)

ボツになる苦しみはよくわかります 心理学の勉強をあきらめ―正確には学校から追い出されて マンガ家になろうと決めたとき自然な流れでしたが 1974から1977年の間に2000枚のマンガを『ニューヨーカー』に送り 全部ボツにされましたこんなボツの通知を 何枚も受け取りましたが― (残念ながら 採用となりませんでした投稿ありがとうございました) 1977年に突然こんなのを受け取ったのです (おぃ!採用だぜ まじで あんたのマンガがあの『ニューヨーカー』に載るんだぜ) (笑) もちろん実際は違いますが 気持ちとしてはこのような感じです もちろん 『ニューヨーカー』のユーモアとも違います

『ニューヨーカー』のユーモアとは? 1977年にマンガが『ニューヨーカー』に掲載されるようになり 1980年には おそれおおくも 『ニューヨーカー』と契約を結びました 中身はぼかしてあります皆さんには関係ありませんからね

1980年にもらった契約書です「マンコフ様 この度は―なんとかかんとか― アイデアスケッチについて契約を結びます」

この「アイデアスケッチ」ですが契約のどこにも 「マンガ」という言葉は見当たりません 実は「アイデアスケッチ」なしに『ニューヨーカー』のマンガはありえません では アイデアスケッチとは何でしょうか? それは見る人に考えさせるものです これはマンガとは違います マンガ家の思考にあなたの考えが合わさって 初めてマンガになるのです (笑)

これを見れば私のいうマンガがどういうものかわかるでしょう

「世界は不公平だこの世界は正しいとも言えるこの世界はすばらしい」

これは「レミングの考え」です (笑)

『ニューヨーカー』と私はコメントをつけました マンガはその意味に曖昧さを残しているものです このマンガの意味は? レミングについてのものか? いいえ 私たちについてです 例えば 宗教についての私の基本的な考えは 宗教間の紛争や論争は全て 誰の空想上の友達が一番かという争いだと思うのです (笑)

これが私の最も有名なマンガです 「いいえ 木曜日はだめですどうでしょう―いっそ会わないというのは?」 何千回もコピーされました 勝手にね 女性の下着にまで 「どうでしょう―いっそ会わないというのは?」この部分だけでしたが

これらは全く違う形のユーモアに見えますが 実は非常に似通っています どちらも私たちの期待を裏切ります どちらもストーリーが予期せぬ展開をします 不一致と対比があるのです 「木曜日はだめです どうでしょう―いっそ会わないというのは?」の中では 慇懃さと無礼さが同じ文の中に 同居しています これがユーモアのしくみです相容れない2つのものを まぜあわせるという認識の相乗効果で 一時的に読者の頭の中に存在させるのです 彼は慇懃であり無礼なのです ここには『ニューヨーカー』の誠実さと 言葉の失礼さがあります これがユーモアのしくみです

私はユーモアアナリストだといえますね E.B.ホワイトは ユーモアの分析はカエルの解剖のようなものだと言いました あまり意味のない事をやってカエルを殺すだけです 私も何匹かは殺しますが大量虐殺はしません でも結果として ― この絵を見てください 笑う観客 大勢の人と しゃれた男が上にいますね 全員が笑っています 全員 たった一人を除いて この男です 誰なのか? 批判者です ユーモアを批判する人です 私はこの立場にいなければならないのです 『ニューヨーカー』にいると危ないのがこれです この男のようになってしまうのです

マット・ディフィー作の短編ビデオがあります 大げさにするとこんな感じになります

ボブ・マンコフ「あーだめだ」 うえぇ おぉ うーん 面白すぎる 普段ならいいけど 今イライラしているんだ ひとりで楽しむとするか たぶんね だめ これも だめ やりすぎ 出来が悪すぎ 絵はいいが面白さが足りない だめ だめ ありえない 全くだめだ

(音楽)

だめ だめ だめ だめ だめ [4時間後] おや これはいいぞ 何持ってきたんだ?

同僚「ライ麦パンのハムチーズサンド?」ボブ・マンコフ「いいや」

同僚「そうか パストラミサンド?」ボブ「いいや」

同僚「スモークターキーとベーコンサンド?」ボブ「いいや」

同僚「ファラフェル?」ボブ「ちょっと見せてくれ」 あぁ いや 同僚「グリルチーズサンド?」ボブ「いいや」 同僚「BLTか?」ボブ「ちがう」

同僚「ハムとモッツァレラとアップルマスタードサンド?」ボブ「いいや」

同僚「インゲンサラダ?」ボブ「いいや」

(音楽)

だめ だめ 全くだめ [ランチから数時間後]

(サイレン)

だめだ さっさと行ってくれ

(笑)

私の仕事を誇張したものですが

確かにたくさんのマンガをボツにします 数が多すぎて「ボツコレクション」なる本が多く出るほどです 「ボツコレクション」は 『ニューヨーカー』には少々そぐわないタイプのユーモアです 歩道のホームレスにお気づきでしょうか 飲んだくれて 腹話術の人形が吐いています これは『ニューヨーカー』のユーモアにはならないでしょうね 実はこれは 本誌の漫画家マット・ディフィーの編集したものです

ボツコレクションのユーモアをいくつかご紹介しましょう

「子どもが欲しいんだ」

(笑)

興味深い―ためらいのある笑いですね 良識に反した笑いです

(笑)

「何もシリません お助けを」

(笑)

この本が意図する 「『ニューヨーカー』では絶対お目にかかれないマンガ」 という意味ではこのユーモアは完璧です ご説明しましょう ユーモアのコンセプトには 無害な違反という考えがあります つまり 何かが面白くあるためには 間違ってはいるが 許されることが必要です 完全に間違っている場合には「それはだめだ」と私たちは言うでしょう 完全に許されるものには何がおかしいのか?ということになりますね 「木曜日はだめです どうでしょう」は無害ですでも「いっそ会わないというのは?」は失礼です ありえない組み合わせなのですが この場面においてはこれで良いと感じるわけです このコレクションの中では「何もシリません お助けを」 これは許される違反です

でも これをニューヨーカーに載せるとなると... 「T細胞の軍隊:体の免疫反応はガン治癒に有用か?」 おやまあ こんな難い記事を 免疫システムの知性あふれる分析を読んでいて ふと目をやると なんと 「何もシリません お助けを」ですって? この違反は許されませんうまくいきませんね どんな場面でも面白いなどというものはありません 全ては状況に左右され私たちの想定内のものなのです

ひとつの見方はこうです これは私たちの見方による動機付けのようなもので モチベーションと気分の問題です 自分の気分によって好き嫌いが左右される というものです 遊び心があるときは刺激を求めます ドキドキさせられることに楽しみを感じます 同じものでも真面目なムードでは不安を招きます 「ボツコレクション」は間違いなくこの部類のマンガです 刺激を受けたい時があります 違反してはみだしたいのです こんな感じ 遊園地のようなものです

声:いくぞ(歓声)

彼は笑っています 危険であり安全な場所にいて 強い刺激をうけているのですジョークはいりません 必要ないのです 人は刺激され 興奮状態になると 何にでも笑い出します

これは「ボツコレクション」の別のマンガです 「きつすぎる?」 これはテロについてのマンガです 『ニューヨーカー』の雰囲気は独特です 独自の遊び心もあれば 真面目でもある その様な場に載せるマンガは独特なものになります

『ニューヨーカー』が9/11直後に出したマンガをお見せしましょう ユーモアにするには非常にデリケートな領域です 『ニューヨーカー』はどうしたのか? 爆弾をもった男が「きつすぎる?」というわけにはいきません お見せしなかった別のマンガもあります 気を悪くする人がいるかと思ったので すばらしいサム・グロスのマンガで ムハンマドの議論のあとに出されましたムハンマドは天国にいて 自爆者がこまぎれになっており ムハンマドが自爆者に言うのです 「きみのペニスを見つけたら乙女が待ってるよ」

(笑)

絵にしないほうがいいでしょう

テロの起きた週はマンガの掲載は休みました ユーモアの出る幕ではなく実にそうでした いつもユーモアが良いわけではありません しかし翌週には最初のマンガを載せました

「二度と笑えるとは思わなかったあなたの服を見るまでは」

これはつまり 生きていれば 笑うこともあるし 息もする 存在していくということですこれは別のマンガです

「3杯目のマティーニを飲まなきゃテロリストの勝ちだと気づいたんだ」

これらはテロ犯についてではなく私たちについての話です ユーモアが私たちの姿を反映しているのです もっとも簡単なユーモアは正当なものではありますが 味方が敵をからかうものです 傾向性のユーモアといわれます ユーモアの95%はこれです私たちのものとは違います

もう1つお見せしましょう

「イスラム原理主義者の国に住みたいものだね」

(笑)

ユーモアにはターゲットが必要です 興味深いことに『ニューヨーカー』のターゲットは私たちです ターゲットとは読者であり ユーモアの作り手です ユーモアは自己の反映で 自分の思いこみについて考えさせてくれます ロズ・チェイストのマンガをご覧ください男性が死亡記事を読んでいます

「2歳年下 12歳年上 3年後輩 ぴったり同い年 まさしく同い年」

これは非常に深いマンガです 『ニューヨーカー』はある意味で マンガに面白さだけでなく私たち自身について 語らせているのですもうひとつ お見せしましょう

「健康のためにベジタリアンなったの それから道徳的な選択としてね今はただ人をいらつかせたいからよ」

(笑)

「すみません ―これちょっとおかしいと思うんです わたし以外 絶対指摘できないような細かいことなんですけど」

これは他の誰でもなく私たちのこだわり ナルシシズム 欠点やうぬぼれをあらわしています

『ニューヨーカー』は読者に なんらかの知的作業を求めているのです ユーモア 芸術 科学の関係について アーサー・ケストラーが「創造活動の理論」に書いたような 二元結合と呼ぶものを求めているのです 違う枠組みからアイデアを組み合わせて しかも素早くしないとマンガは理解できません 違う枠組み同士を0.5秒以内に 組みあわせられなければ面白さはないのです これはわかりやすいものです 違う枠組みです

「彼女と寝たんでしょ」

(笑)

「ラッシー!誰か呼んで!!」

(笑)

これは「フレンチアーミーナイフ」

(笑)

これはアインシュタインの寝室です「あなたにとっては一瞬だったのね」

(笑)

ちょっと難しいマンガもあります これは解りにくいでしょう このマンガの意味をどれくらいの人がわかるでしょうか 犬が散歩に行きたいというサインを出しています キャッチャーはバッターを「歩かせろ」というサインをしています 毎年マンガ特集をするのはこのためです 「意味不明 : ニューヨーカーのマンガ IQテスト」 (笑)

もうひとつ『ニューヨーカー』が好きなのが 場違いさですお見せしたとおり ユーモアの基本になるものです あまりにも当然で論理的なものはおもしろくありません 場違いが機能するのは 観察に基づく 現実の範囲内のユーモアです

「上司がいつも あれこれ指示するんだ」 これはありえることです現実の範囲内のユーモアです

ここでは カウボーイが牛に言っています 「すばらしい あなたの様な方を あと5000頭くらい欲しいですね」

これは理解できます むちゃくちゃですがふたつをつなぎあわせることができます

これはもうナンセンスです

「ホプキンズ君 困るな 連絡事項はきちんと読んでくれないと」

これはちょっと難しいですねうまくつながりません 一般的にナンセンスを楽しむ人は より抽象的な芸術が好きです 保守的よりもリベラルなタイプです しかし私たち 私にとってユーモアをつくる手助けをするとき それぞれを比較しても意味はありません いろいろあるから面白いんです

このマンガのキャプションで今日の話をまとめたいと思います 『ニューヨーカー』のマンガについて うまくまとめていると思います

「立ち止まって 考えさせられるよな」

(笑)

ニューヨーカーのマンガを見るときには 立ち止まってすこし考えてみて頂きたいのです

ありがとう

(拍手) ありがとう(拍手)

品詞分類

- 主語

- 動詞

- 助動詞

- 準動詞

- 関係詞等

TED 日本語

TED Talks

関連動画

アーティストは経済にどう貢献し、私たちは彼らをどう支えられるか?ハディ・エルデベック

2018.04.09

コンテンツを流行らせる要素とは?ダオ・グエン

2018.01.08

私がアートを制作するのは、伝統を受け継ぐタイムカプセルを作るためケイラ・ブリエット

2017.12.08

ニューヨーカー誌、象徴的な表紙イラストの舞台裏フランソワーズ・ムーリー

2017.08.17

とらえ難い心情を表す素敵な新語の数々ジョン・ケーニック

2017.03.31

2千本のおくやみ記事から学んだことラックス・ナラヤン

2017.03.23

メロドラマが教えてくれる4つの大げさな人生訓ケイト・アダムス

2017.01.03

音楽がもたらしたコンピューターの発明スティーヴン・ジョンソン

2016.12.09

Ideas worth dating -- デートする価値のあるアイデアレイン・ウィルソン

2016.10.30

購読解除の苦悩!ジェイムズ・ヴィーチ

2016.09.27

コスプレへの愛アダム・サヴェッジ

2016.08.23

「アンチ」を科学的に分類してみようネギン・ファルサド

2016.07.05

データで描く、示唆に富む肖像画ルーク・デュボワ

2016.05.19

詐欺メール 返信すると どうなるかジェイムズ・ヴィーチ

2016.02.01

世界中の国の本を1冊ずつ読んでいく私の1年アン・モーガン

2015.12.21

日常の音に隠された思いがけない美とはメクリト・ハデロ

2015.11.10

洋楽 おすすめ

RECOMMENDS

洋楽歌詞

ダイナマイトビーティーエス

洋楽最新ヒット2020.08.20

ディス・イズ・ミーグレイテスト・ショーマン・キャスト

洋楽人気動画2018.01.11

グッド・ライフGイージー、ケラーニ

洋楽人気動画2017.01.27

ホワット・ドゥ・ユー・ミーン?ジャスティン・ビーバー

洋楽人気動画2015.08.28

ファイト・ソングレイチェル・プラッテン

洋楽人気動画2015.05.19

ラヴ・ミー・ライク・ユー・ドゥエリー・ゴールディング

洋楽人気動画2015.01.22

アップタウン・ファンクブルーノ・マーズ、マーク・ロンソン

洋楽人気動画2014.11.20

ブレイク・フリーアリアナ・グランデ

洋楽人気動画2014.08.12

ハッピーファレル・ウィリアムス

ポップス2014.01.08

カウンティング・スターズワンリパブリック

ロック2013.05.31

ア・サウザンド・イヤーズクリスティーナ・ペリー

洋楽人気動画2011.10.26

ユー・レイズ・ミー・アップケルティック・ウーマン

洋楽人気動画2008.05.30

ルーズ・ユアセルフエミネム

洋楽人気動画2008.02.21

ドント・ノー・ホワイノラ・ジョーンズ

洋楽人気動画2008.02.15

オンリー・タイムエンヤ

洋楽人気動画2007.10.03

ミス・ア・シングエアロスミス

ロック2007.08.18

タイム・トゥ・セイ・グッバイサラ・ブライトマン

洋楽人気動画2007.06.08

シェイプ・オブ・マイ・ハートスティング

洋楽人気動画2007.03.18

ウィ・アー・ザ・ワールド(U.S.A. フォー・アフリカ)マイケル・ジャクソン

洋楽人気動画2006.05.14

ホテル・カリフォルニアイーグルス

ロック2005.07.06