TED日本語

TED Talks(英語 日本語字幕付き動画)

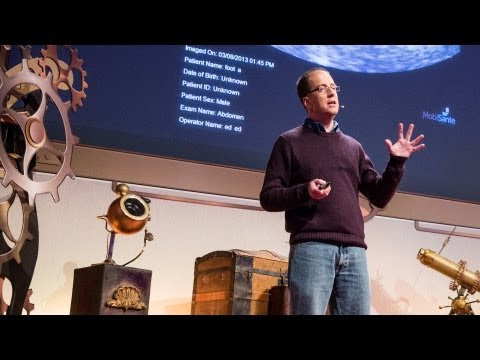

TED日本語 - エイブラハム・バルギーズ: 医師の手が持つ力

TED Talks

医師の手が持つ力

A doctor's touch

エイブラハム・バルギーズ

Abraham Verghese

内容

近代医療は、人の手が持つ力という、昔からある強力なツールを失いつつあります。医師であり作家でもあるエイブラハム・バルギーズは、患者がもはやパソコン上のデータに過ぎなくなった現代社会の奇妙さを描き、昔ながらの一対一の診察への回帰を呼びかけます。

字幕

SCRIPT

Script

A few months ago, a 40 year-old woman came to an emergency room in a hospital close to where I live, and she was brought in confused. Her blood pressure was an alarming 230 over 170. Within a few minutes, she went into cardiac collapse. She was resuscitated, stabilized, whisked over to a CAT scan suite right next to the emergency room, because they were concerned about blood clots in the lung. And the CAT scan revealed no blood clots in the lung, but it showed bilateral, visible, palpable breast masses, breast tumors, that had metastasized widely all over the body. And the real tragedy was, if you look through her records, she had been seen in four or five other health care institutions in the preceding two years. Four or five opportunities to see the breast masses, touch the breast mass, intervene at a much earlier stage than when we saw her.

Ladies and gentlemen, that is not an unusual story. Unfortunately, it happens all the time. I joke, but I only half joke, that if you come to one of our hospitals missing a limb, no one will believe you till they get a CAT scan, MRI or orthopedic consult. I am not a Luddite. I teach at Stanford. I'm a physician practicing with cutting-edge technology. But I'd like to make the case to you in the next 17 minutes that when we shortcut the physical exam, when we lean towards ordering tests instead of talking to and examining the patient, we not only overlook simple diagnoses that can be diagnosed at a treatable, early stage, but we're losing much more than that. We're losing a ritual. We're losing a ritual that I believe is transformative, transcendent, and is at the heart of the patient-physician relationship. This may actually be heresy to say this at TED, but I'd like to introduce you to the most important innovation, I think, in medicine to come in the next 10 years, and that is the power of the human hand -- to touch, to comfort, to diagnose and to bring about treatment.

I'd like to introduce you first to this person whose image you may or may not recognize. This is Sir Arthur Conan Doyle. Since we're in Edinburgh, I'm a big fan of Conan Doyle. You might not know that Conan Doyle went to medical school here in Edinburgh, and his character, Sherlock Holmes, was inspired by Sir Joseph Bell. Joseph Bell was an extraordinary teacher by all accounts. And Conan Doyle, writing about Bell, described the following exchange between Bell and his students.

So picture Bell sitting in the outpatient department, students all around him, patients signing up in the emergency room and being registered and being brought in. And a woman comes in with a child, and Conan Doyle describes the following exchange. The woman says, "Good Morning." Bell says, "What sort of crossing did you have on the ferry from Burntisland?" She says, "It was good." And he says, "What did you do with the other child?" She says, "I left him with my sister at Leith." And he says, "And did you take the shortcut down Inverleith Row to get here to the infirmary?" She says, "I did." And he says, "Would you still be working at the linoleum factory?" And she says, "I am."

And Bell then goes on to explain to the students. He says, "You see, when she said, 'Good morning,' I picked up her Fife accent. And the nearest ferry crossing from Fife is from Burntisland. And so she must have taken the ferry over. You notice that the coat she's carrying is too small for the child who is with her, and therefore, she started out the journey with two children, but dropped one off along the way. You notice the clay on the soles of her feet. Such red clay is not found within a hundred miles of Edinburgh, except in the botanical gardens. And therefore, she took a short cut down Inverleith Row to arrive here. And finally, she has a dermatitis on the fingers of her right hand, a dermatitis that is unique to the linoleum factory workers in Burntisland." And when Bell actually strips the patient, begins to examine the patient, you can only imagine how much more he would discern. And as a teacher of medicine, as a student myself, I was so inspired by that story.

But you might not realize that our ability to look into the body in this simple way, using our senses, is quite recent. The picture I'm showing you is of Leopold Auenbrugger who, in the late 1700s, discovered percussion. And the story is that Leopold Auenbrugger was the son of an innkeeper. And his father used to go down into the basement to tap on the sides of casks of wine to determine how much wine was left and whether to reorder. And so when Auenbrugger became a physician, he began to do the same thing. He began to tap on the chests of his patients, on their abdomens. And basically everything we know about percussion, which you can think of as an ultrasound of its day -- organ enlargement, fluid around the heart, fluid in the lungs, abdominal changes -- all of this he described in this wonderful manuscript "Inventum Novum," "New Invention," which would have disappeared into obscurity, except for the fact that this physician, Corvisart, a famous French physician -- famous only because he was physician to this gentleman -- Corvisart repopularized and reintroduced the work.

And it was followed a year or two later by Laennec discovering the stethoscope. Laennec, it is said, was walking in the streets of Paris and saw two children playing with a stick. One was scratching at the end of the stick, another child listened at the other end. And Laennec thought this would be a wonderful way to listen to the chest or listen to the abdomen using what he called "the cylinder." Later he renamed it the stethoscope. And that is how stethoscope and auscultation was born. So within a few years, in the late 1800s, early 1900s, all of a sudden, the barber surgeon had given way to the physician who was trying to make a diagnosis.

If you'll recall, prior to that time, no matter what ailed you, you went to see the barber surgeon who wound up cupping you, bleeding you, purging you. And, oh yes, if you wanted, he would give you a haircut -- short on the sides, long in the back -- and pull your tooth while he was at it. He made no attempt at diagnosis. In fact, some of you might well know that the barber pole, the red and white stripes, represents the blood bandages of the barber surgeon, and the receptacles on either end represent the pots in which the blood was collected. But the arrival of auscultation and percussion represented a sea change, a moment when physicians were beginning to look inside the body.

And this particular painting, I think, represents the pinnacle, the peak, of that clinical era. This is a very famous painting: "The Doctor" by Luke Fildes. Luke Fildes was commissioned to paint this by Tate, who then established the Tate Gallery. And Tate asked Fildes to paint a painting of social importance. And it's interesting that Fildes picked this topic. Fildes' oldest son, Philip, died at the age of nine on Christmas Eve after a brief illness. And Fildes was so taken by the physician who held vigil at the bedside for two,three nights, that he decided that he would try and depict the physician in our time -- almost a tribute to this physician. And hence the painting "The Doctor," a very famous painting. It's been on calendars, postage stamps in many different countries. I've often wondered, what would Fildes have done had he been asked to paint this painting in the modern era, in the year 2011? Would he have substituted a computer screen for where he had the patient?

I've gotten into some trouble in Silicon Valley for saying that the patient in the bed has almost become an icon for the real patient who's in the computer. I've actually coined a term for that entity in the computer. I call it the iPatient. The iPatient is getting wonderful care all across America. The real patient often wonders, where is everyone? When are they going to come by and explain things to me? Who's in charge? There's a real disjunction between the patient's perception and our own perceptions as physicians of the best medical care.

I want to show you a picture of what rounds looked like when I was in training. The focus was around the patient. We went from bed to bed. The attending physician was in charge. Too often these days, rounds look very much like this, where the discussion is taking place in a room far away from the patient. The discussion is all about images on the computer, data. And the one critical piece missing is that of the patient.

Now I've been influenced in this thinking by two anecdotes that I want to share with you. One had to do with a friend of mine who had a breast cancer, had a small breast cancer detected -- had her lumpectomy in the town in which I lived. This is when I was in Texas. And she then spent a lot of time researching to find the best cancer center in the world to get her subsequent care. And she found the place and decided to go there, went there. Which is why I was surprised a few months later to see her back in our own town, getting her subsequent care with her private oncologist.

And I pressed her, and I asked her, "Why did you come back and get your care here?" And she was reluctant to tell me. She said, "The cancer center was wonderful. It had a beautiful facility, giant atrium, valet parking, a piano that played itself, a concierge that took you around from here to there. But," she said, "but they did not touch my breasts." Now you and I could argue that they probably did not need to touch her breasts. They had her scanned inside out. They understood her breast cancer at the molecular level; they had no need to touch her breasts.

But to her, it mattered deeply. It was enough for her to make the decision to get her subsequent care with her private oncologist who, every time she went, examined both breasts including the axillary tail, examined her axilla carefully, examined her cervical region, her inguinal region, did a thorough exam. And to her, that spoke of a kind of attentiveness that she needed. I was very influenced by that anecdote.

I was also influenced by another experience that I had, again, when I was in Texas, before I moved to Stanford. I had a reputation as being interested in patients with chronic fatigue. This is not a reputation you would wish on your worst enemy. I say that because these are difficult patients. They have often been rejected by their families, have had bad experiences with medical care and they come to you fully prepared for you to join the long list of people who's about to disappoint them. And I learned very early on with my first patient that I could not do justice to this very complicated patient with all the records they were bringing in a new patient visit of 45 minutes. There was just no way. And if I tried, I'd disappoint them.

And so I hit on this method where I invited the patient to tell me the story for their entire first visit, and I tried not to interrupt them. We know the average American physician interrupts their patient in 14 seconds. And if I ever get to heaven, it will be because I held my piece for 45 minutes and did not interrupt my patient. I then scheduled the physical exam for two weeks hence, and when the patient came for the physical, I was able to do a thorough physical, because I had nothing else to do. I like to think that I do a thorough physical exam, but because the whole visit was now about the physical, I could do an extraordinarily thorough exam.

And I remember my very first patient in that series continued to tell me more history during what was meant to be the physical exam visit. And I began my ritual. I always begin with the pulse, then I examine the hands, then I look at the nail beds, then I slide my hand up to the epitrochlear node, and I was into my ritual. And when my ritual began, this very voluble patient began to quiet down. And I remember having a very eerie sense that the patient and I had slipped back into a primitive ritual in which I had a role and the patient had a role. And when I was done, the patient said to me with some awe, "I have never been examined like this before." Now if that were true, it's a true condemnation of our health care system, because they had been seen in other places.

I then proceeded to tell the patient, once the patient was dressed, the standard things that the person must have heard in other institutions, which is, "This is not in your head. This is real. The good news, it's not cancer, it's not tuberculosis, it's not coccidioidomycosis or some obscure fungal infection. The bad news is we don't know exactly what's causing this, but here's what you should do, here's what we should do." And I would lay out all the standard treatment options that the patient had heard elsewhere.

And I always felt that if my patient gave up the quest for the magic doctor, the magic treatment and began with me on a course towards wellness, it was because I had earned the right to tell them these things by virtue of the examination. Something of importance had transpired in the exchange. I took this to my colleagues at Stanford in anthropology and told them the same story. And they immediately said to me, "Well you are describing a classic ritual." And they helped me understand that rituals are all about transformation.

We marry, for example, with great pomp and ceremony and expense to signal our departure from a life of solitude and misery and loneliness to one of eternal bliss. I'm not sure why you're laughing. That was the original intent, was it not? We signal transitions of power with rituals. We signal the passage of a life with rituals. Rituals are terribly important. They're all about transformation. Well I would submit to you that the ritual of one individual coming to another and telling them things that they would not tell their preacher or rabbi, and then, incredibly on top of that, disrobing and allowing touch -- I would submit to you that that is a ritual of exceeding importance. And if you shortchange that ritual by not undressing the patient, by listening with your stethoscope on top of the nightgown, by not doing a complete exam, you have bypassed on the opportunity to seal the patient-physician relationship.

I am a writer, and I want to close by reading you a short passage that I wrote that has to do very much with this scene. I'm an infectious disease physician, and in the early days of HIV, before we had our medications, I presided over so many scenes like this. I remember, every time I went to a patient's deathbed, whether in the hospital or at home, I remember my sense of failure -- the feeling of I don't know what I have to say; I don't know what I can say; I don't know what I'm supposed to do. And out of that sense of failure, I remember, I would always examine the patient. I would pull down the eyelids. I would look at the tongue. I would percuss the chest. I would listen to the heart. I would feel the abdomen. I remember so many patients, their names still vivid on my tongue, their faces still so clear. I remember so many huge, hollowed out, haunted eyes staring up at me as I performed this ritual. And then the next day, I would come, and I would do it again.

And I wanted to read you this one closing passage about one patient. "I recall one patient who was at that point no more than a skeleton encased in shrinking skin, unable to speak, his mouth crusted with candida that was resistant to the usual medications. When he saw me on what turned out to be his last hours on this earth, his hands moved as if in slow motion. And as I wondered what he was up to, his stick fingers made their way up to his pajama shirt, fumbling with his buttons. I realized that he was wanting to expose his wicker-basket chest to me. It was an offering, an invitation. I did not decline.

I percussed. I palpated. I listened to the chest. I think he surely must have known by then that it was vital for me just as it was necessary for him. Neither of us could skip this ritual, which had nothing to do with detecting rales in the lung, or finding the gallop rhythm of heart failure. No, this ritual was about the one message that physicians have needed to convey to their patients. Although, God knows, of late, in our hubris, we seem to have drifted away. We seem to have forgotten -- as though, with the explosion of knowledge, the whole human genome mapped out at our feet, we are lulled into inattention, forgetting that the ritual is cathartic to the physician, necessary for the patient -- forgetting that the ritual has meaning and a singular message to convey to the patient.

And the message, which I didn't fully understand then, even as I delivered it, and which I understand better now is this: I will always, always, always be there. I will see you through this. I will never abandon you. I will be with you through the end."

Thank you very much.

(Applause)

ほんの数ヶ月前 私の近所のとある病院に 40代の女性が意識不明で 担ぎ込まれました 血圧は 危険領域に達し 数分後 心肺停止状態となりました すぐさま 蘇生処置がほどこされ 救命室の隣のCATスキャンへ 運ばれました 肺に血栓の疑いがあったのです スキャンの結果 血栓こそありませんでしたが なんと両方の乳房に明らかな 癌の腫瘍が見られ 体中に 転移していました ひどい話ですが カルテによると 過去数年間に 数箇所の医療機関で 受診歴があるのです ということは こうなる前に 乳房のしこりが発見され 早期に対処が できたかもしれないということです

みなさん 珍しい例ではありません 残念ながらどこででもありえます 半分はジョークですが 脚を失った状態で 病院に来ても CATスキャン MRIといった検査を受けるまで 誰も気づかないでしょう 先端技術が嫌いなわけじゃありません スタンフォードで教えてますし こうした技術も利用しています しかし この17分間でご紹介したいのは 患者と話をし 触れて診察を行う代りに 検査に偏重し 患者との ふれあいを省略すると まだ初期段階の 治癒可能な 症状を見過ごしてしまうだけではなく もっと大切な「儀式」が 失われてしまうのです これには 医師と患者の関係に 変化をおこし 強力にする 力があるのです TEDでご紹介するのは 場違いかもしれませんが 今後10年間における もっとも重要な イノベーションは 人の手の持つ力でしょう 触れて 癒し 診察する そして治療を行う

まずはこの人物をご紹介します お気づきの方もいるでしょう アーサー・コナン・ドイルです 私はコナン・ドイルの大ファンです ここエジンバラで 彼は医学を 学んだ経験もあります シャーロック・ホームズは ジョセフ・ベルにインスパイアされました あらゆる点で ジョセフ・ベルは優れた教師で コナン・ドイルは ベルと生徒とのやりとりについて こんな逸話を残しています

想像してください ベルは外来で 生徒は彼を取り巻き 受付を済ませた患者が 処置室にやって来ます 彼女は子供を連れていました コナン・ドイルはこんな会話を残しています 「おはようございます」患者は言いました 「バーンティスランドからのフェリーは いかがだったかな?」ベルは言います 「よかったですよ」患者は答えます 「もう一人のお子さんはどうしたのかな?」ベルは言います 「リースの姉に預けて来ました」 彼は続けます 「ここに来る時に 植物園を通って 近道をしたんじゃないかね?」 「そうです」患者は答えます 「今も リノリウム工場で働いているのかね?」 「そうです」患者は答えます

ベルは生徒達に説明し始めました 「彼女が挨拶した時 ファイフ訛りと気づいてね ファイフから最寄のフェリーはバーンティスランドだ だからフェリーを使ったに違いないと そして 彼女が持っているコートを見ると 連れている子供のものにしては小さすぎると なので 最初は2人連れて出発し 途中で一人を預けたのだろうと 靴底の土に気づいてね エジンバラの周辺には こんな赤土は存在しない 植物園を除いてはね だから 彼女は植物園を通って 近道したんだなと 最後に 彼女の右手の指には 皮膚炎が見られる この皮膚炎はバーンティスランドの リノリウム工場の工員に独特のものなんだ」 ベルは実際に服を脱がせ 診察を始める前に なんと多くの情報を得ていたことか 医学の教師であり また生徒でもある私は この話に大変感銘を受けました

しかしながら 医師の知覚という単純な手段で 体の中が調べられるようになったのは ごく近年のことです こちらは レオポルト・アウエンブルッカー 1,700年代 彼により 打診法が開発されました きっかけは 彼の父親が 居酒屋の主人であったことです 父親はワイン樽をコツコツ叩いて ワインの残量を測っていました ワインの追加注文のタイミングを 決めるためです アウエンブルッカーは医師となり 同じことをはじめました 患者の胸部や腹部を叩く診察法を はじめました 打診はいわば当時の超音波診断ですが 今日知られている全て -臓器肥大も 心嚢水も肺水腫も 腹部の異変なども全て この優れた著書に記されています 「新発見」 この手法は忘れさられるところでした 著名なフランスの医師 コルヴィザール- 彼はこちらの紳士の 主治医であったことのみで有名でしたが- 彼は打診法を復活させました

1~2年後にラエンエックにより 聴診器が発明されるに至ります 彼がある日 パリを歩いていた時のこと 棒で遊んでいる二人の子供を見かけました 一人が端っこを引っかいて もう一人が別の端っこで音を聞いていました ラエンネックは思いつきました これは 体内の音を聴くのに 良い方法だと これをシリンダーと彼は名付け のちに 聴診器と改名し こうして聴診器と聴診が生まれたのです 18世紀の終わりから 19世紀初頭の数年間で 急激に 手術を行う理髪店は 診察を行う医師に取って代わられました

当時の人々は どんな症状であっても こうした理髪店に行っていました そこでは吸引療法 血抜き療法 洗浄療法 そして お望みなら もちろん髪も切ってくれました おまけに歯だって抜いてくれます ただ 診察は全くありません 事実 ご存知の方もいるでしょうか 理髪店の赤と白の縞模様のポールは 血に染まった包帯からきたものなんです 両端の物体は 血液を集める容器を表しています 聴診と打診の登場は 転換期を象徴するものでした 医師が患者の体内に注目しはじめたのです

個人的には こちらの絵は そうした決定的な時代の頂点を表しています とても有名な絵で ルーク・フィルデス作 「医師」 彼はテート美術館の創立者である テート氏の依頼により描きました 社会的に影響力のある絵画を頼む と 依頼されたのです 医師がテーマに選ばれた興味深い話があります フィルデスの長男のフィリップは 9つのとき 短期間の病を経て クリスマス・イヴに亡くなりました 息子の横で数日に及び 寝ずの看病を続けた医師に感動したフィルデスは 医師の姿を描こうと 決めたのです この医師に捧げるためでした 「医師」はとても有名で 各国でカレンダーや切手のデザインになってます よく思うんです もしフィルデスが 2011年にこの絵画を依頼されたなら 一体何を 描くのだろうと 患者のかわりにパソコン画面を もってくるのでは?

シリコンバレーで批判を受けました 「患者はもはや パソコン上のデータに 過ぎなくなった」と言ったのです そうしたデータに名前まで付けました アイ・ペイシャントです 全米でデータは手厚いケアを受ける一方 本物の患者は思います 「みんなどこ?」 「いつになったら僕のところに説明にくるの?」 「担当者は誰?」 一流の治療の定義は患者と 我々医師の間ではかけ離れたものになっています

こちらをご覧いただきましょう 私が研修医の頃の 回診の様子です 中心には患者がいました ベッドからベッドへ 主治医が回ります 最近では 回診の様子はこうです 議論は患者から遠く離れた 会議室で行われます 議論の中心はパソコン上のイメージとデータのみ 不可欠な要素である 患者本人が抜け落ちています

では 私が影響を受けた 2つのエピソードをご紹介したいと思います 一つ目は乳がんを患った友人の話です 小さな乳がんが発見され 私の住む地元で摘出手術を受けました 私がテキサスにいた頃です その後 術後のケアのため 彼女は世界で一番のがんセンターを 探しはじめました お目当ての場所が見つかり 彼女はそこに行ったんです なので数ヵ月後 町に戻った彼女を見かけて 私は驚きました ここで 地元の癌専門医に通っていたのです

彼女に聞きました 「なぜここでケアを受けることにしたの?」 彼女はためらいながらも言いました 「がんセンターはステキだったわ 施設も立派だし 巨大な 吹き抜けに バレー・パーキング 自動のピアノだってあるの あちこち連れてってくれる世話人もいるしね」 「でもね そこでは 胸に一度も触わらなかったの」 胸に触る必要さえなかったと 言えなくもありません 彼女のデータはスキャンされ 彼女の乳がんは分子レベルで把握され 触る必要さえなかったわけです

でも 彼女にとっては 病院を変えさせるくらい 重要な要素だったのです 今の医者は毎回 両方の乳房をわきの下も含め じっくり診察し 首まわり 股のあたりもじっくりと 診察します 彼女は こうした手厚いケアを求めていたのです この話に私は大いに影響を受けました

もう一つ影響を受けた経験をお話しましょう スタンフォードに移る前 テキサス時代の話です 当時 私には 慢性疲労患者の専門医 という評判がありました 好ましい評判ではありません というのも なにせ手強い相手です こうした患者は家族から見放され 医療機関では苦い経験をし 私の所に来る頃には もう期待などない状態 なんですから まさに最初のこうした患者を診察した時 彼らが持ってくる これまでの診察記録は 初診の45分間で 症状を把握するには 全く役に立たないことが分かりました また同じ事の繰り返しです

そこで ある方法を思いつきました 初診では 全ての時間を使って 患者に自分の状態を語ってもらうのです 中断せずじっと聞くことにしました アメリカでは平均的な医師は 患者の話に14秒で割って入ります もし私が天国にいけるなら 患者の話を中断することなく 45分聞き続けたからでしょう 2週間後に仕切りなおして 診察をします その時には じっくりと診断ができます 他にする事が無いのですから 徹底的に診察するのは その回が診察のための回だからという理由でなく とてつもなく詳細に診察するためです

こうした診察回に最初に訪れた患者は 最初 自身の症状をとうとうと 語り始めました この回は診察のための回というのに そこで私も手順に従って まず脈を図ります そして患者の手を 爪床をチェックします 手を滑らせながら肘のリンパ腺へ- いつもの手順です 私の手順が始まると このおしゃべりな患者が 静かになり 不思議な感覚を覚えました 患者と私は なにか 原始的な儀式を行っているという感覚 私には役割があり そして患者にも役割がある 診察が終わった際 患者は畏敬の念とともに言いました こんな風に診察されたのは始めてです さて これが事実なら 現代の医療システムに 問題があるということです

そして 私は患者が服を着た後 診察結果を説明します 他の医療機関でも聞いたであろう内容です 「あなたの思い込みではなく 病気は存在します 良いニュースは 癌や結核 はたまた なにか恐ろしい感染症ではありません 悪いニュースは一体何が原因かわからないことです では まずあなたがすべき事と 私達がすべき事です…」 こうして私は患者に通常の治療法を説明します 他でも聞いた内容なのです

よく思うのが もし 私の患者が ありもしない 名医や特効薬を探すのはやめて 私と治療へのプロセスを歩み始めてくれるなら それは 徹底的な診察の結果として 治療法を説明するに必要な 信頼を築いたからだと思います 診察を通して 何か重要なものが生まれたのだと思います スタンフォードで 人類学を教える同僚たちに この話をしてみました 彼らはすぐに答えました 「それは古典的な儀式のことだね」と 彼らによると 儀式とは つまるところ 変化であると

例えば 私たちは 豪華な結婚式を行います 寂しい独り身から 永遠の祝福への出発を お祝いしているわけです なぜ みなさん笑っているのでしょうか? もともとはそういう意味だったでしょ? 儀式こそがこうした変化を知らせる シグナルなのです 人生の節々でこうしたシグナルを出します 儀式はとても大事なものなのです 儀式とは変化を表すものです ある人が とある人を訪れ 牧師やラビには 言いたくないことを伝え 驚くべきことに 服を脱ぎ 体を触らせるという儀式- こうした儀式がとても重要なのです 服を着せたまま診察したり ガウンの上から聴診したり 徹底的な診察をせず こうしたことで 儀式を省略すると 患者と医師の関係をつなぐ機会を 失うことになるのです

私が書いた 短い一節を読みまして 終わりにします ご覧のようなシーンと関係します 私は感染症の専門医で エイズが認識されはじめ まだ治療法も無い頃 こうした光景に立ち会うことが多々ありました 患者の臨終の床に立ち会う際 それが患者の自宅でも病院でも 常に挫折を感じていました- 何を言わなければいけないのかー 何を言っていいのかー 何をすべきかも分かりません そうした挫折感から いつも患者を診察するようにしていました まぶたをめくり 舌を見て 胸部を打診し 心音を聴きます そして 腹部をさすります 私は多くの患者の 名前や顔は今でも はっきり覚えています 大きく 窪み おびえたような目が 儀式を行う私を見上げていました 翌日も また私は同じ事を行うのです

では 最後となる一節を読みたいと思います ある患者の話です 「ある患者を思い出す 彼はその時点で 皮に包まれた 骸骨と化していた 話すことはできず 普通の薬の効かない カンジダで 口もカサブタだらけ 亡くなる数時間前のことだった 彼は私を目にすると スローモーションで手を動かし始めた 何をしようとしているのか? 小枝のような指は パジャマのシャツを目指すが ボタンがつまめない 診察してもらうため 痩せた胸を出したいのだと私は気づいた このような提案を-勧誘を 断ることなどできない

打診し 触診し そして胸部の音を聴く 彼はその時点で気づいていたに違いないだろう これが自分にとって必要なだけではなく 私にも不可欠なことだと お互いに省略するわけに行かない儀式なのだ 肺の水泡を見つけるためではなく 心音の異常を探すこととは全く関係なく 医師が患者に伝えるべき あのメッセージを伝えるための儀式なのだ 傲慢になった私たちは そこから押し流され 忘れてしまったかのようだ 知識を急速に増大させ 人間の遺伝子地図を踏破しつくし 無関心に陥ったかのようだ 儀式が医師の癒しであり 患者に欠かせないことが忘れられ 儀式の持つ意味と 患者に伝えるべき唯一のメッセージが忘れられている

当時の私が伝えつつも 理解は十分ではなかったが 今ではよく分かるようになったメッセージである 私はいつもいつも ここにいて 最後まで見届けます 決して見捨てません 最後まで一緒です」

どうもありがとうございました

(拍手)

品詞分類

- 主語

- 動詞

- 助動詞

- 準動詞

- 関係詞等

TED 日本語

TED Talks

関連動画

死に直面したとき、人生に生きる価値を与えてくれるのはルーシー・カラニシ

おすすめ 12017.06.07

末期小児患者たちのための家からの物語キャシー・ハル

2017.03.24

もしも医者には診断できない病に倒れたら?ジェン・ブレア

2017.01.17

医者が社会正義を求めるべき理由メアリー・バセット

2016.03.17

人生を終えるとき本当に大切なことBJ・ミラー

おすすめ 22015.09.30

いかに子供時代のトラウマが生涯に渡る健康に影響を与えるのかナディン・バーク・ハリス

TED人気動画2015.02.17

医師が開示しようとしないことリアナ・ウェン

2014.11.13

ええ、私は癌を克服しましたが、この体験で私という人間を決めつけないでデブラ・ジャービス

2014.10.30

世界の医師たちを訓練するにはどこがいい?それはキューバゲイル・リード

2014.10.01

「私は死ぬのでしょうか?」真実を答えるマシュー・オライリー

2014.09.25

病気の上流を診る医療リシ・マンチャンダ

2014.09.15

彼、そして彼女の...ヘルスケアポーラ・ジョンソン

2014.01.22

死に向かう勇敢な物語アマンダ・ベネット

2013.10.15

最速の救急車はバイク型エリ・ビア

2013.07.30

我が子の病気から学んだ人生の教訓ロベルト・ダンジェロ + フランチェスカ・フェデリ

2013.07.24

チームで運営するヘルス・ケアエリック・デイシュマン

2013.04.11

洋楽 おすすめ

RECOMMENDS

洋楽歌詞

ダイナマイトビーティーエス

洋楽最新ヒット2020.08.20

ディス・イズ・ミーグレイテスト・ショーマン・キャスト

洋楽人気動画2018.01.11

グッド・ライフGイージー、ケラーニ

洋楽人気動画2017.01.27

ホワット・ドゥ・ユー・ミーン?ジャスティン・ビーバー

洋楽人気動画2015.08.28

ファイト・ソングレイチェル・プラッテン

洋楽人気動画2015.05.19

ラヴ・ミー・ライク・ユー・ドゥエリー・ゴールディング

洋楽人気動画2015.01.22

アップタウン・ファンクブルーノ・マーズ、マーク・ロンソン

洋楽人気動画2014.11.20

ブレイク・フリーアリアナ・グランデ

洋楽人気動画2014.08.12

ハッピーファレル・ウィリアムス

ポップス2014.01.08

カウンティング・スターズワンリパブリック

ロック2013.05.31

ア・サウザンド・イヤーズクリスティーナ・ペリー

洋楽人気動画2011.10.26

ユー・レイズ・ミー・アップケルティック・ウーマン

洋楽人気動画2008.05.30

ルーズ・ユアセルフエミネム

洋楽人気動画2008.02.21

ドント・ノー・ホワイノラ・ジョーンズ

洋楽人気動画2008.02.15

オンリー・タイムエンヤ

洋楽人気動画2007.10.03

ミス・ア・シングエアロスミス

ロック2007.08.18

タイム・トゥ・セイ・グッバイサラ・ブライトマン

洋楽人気動画2007.06.08

シェイプ・オブ・マイ・ハートスティング

洋楽人気動画2007.03.18

ウィ・アー・ザ・ワールド(U.S.A. フォー・アフリカ)マイケル・ジャクソン

洋楽人気動画2006.05.14

ホテル・カリフォルニアイーグルス

ロック2005.07.06