TED日本語

TED Talks(英語 日本語字幕付き動画)

TED日本語 - デニス・ダットン: 美の進化論的起源

TED Talks

美の進化論的起源

A Darwinian theory of beauty

デニス・ダットン

Denis Dutton

内容

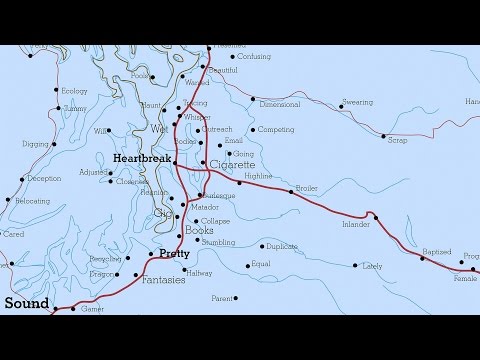

美術や音楽といったものが持つ美は単に「見る人の目の中にある」のではなく、進化に深い起源を持つ人間本性の一部なのだというデニス・ダットンの美に関する挑発的な理論を、アニメーターのアンドリュー・パークの協力を得て図解しています。

字幕

SCRIPT

Script

Delighted to be here and to talk to you about a subject dear to my heart, which is beauty. I do the philosophy of art, aesthetics, actually, for a living. I try to figure out intellectually, philosophically, psychologically, what the experience of beauty is, what sensibly can be said about it and how people go off the rails in trying to understand it. Now this is an extremely complicated subject, in part because the things that we call beautiful are so different. I mean just think of the sheer variety -- a baby's face, Berlioz's "Harold in Italy," movies like "The Wizard of Oz" or the plays of Chekhov, a central California landscape, a Hokusai view of Mt. Fuji, "Der Rosenkavalier," a stunning match-winning goal in a World Cup soccer match, Van Gogh's "Starry Night," a Jane Austen novel, Fred Astaire dancing across the screen. This brief list includes human beings, natural landforms, works of art and skilled human actions. An account that explains the presence of beauty in everything on this list is not going to be easy.

I can, however, give you at least a taste of what I regard as the most powerful theory of beauty we yet have. And we get it not from a philosopher of art, not from a postmodern art theorist or a bigwig art critic. No, this theory comes from an expert on barnacles and worms and pigeon breeding, and you know who I mean: Charles Darwin. Of course, a lot of people think they already know the proper answer to the question, "What is beauty?" It's in the eye of the beholder. It's whatever moves you personally. Or, as some people, especially academics prefer, beauty is in the culturally conditioned eye of the beholder. People agree that paintings or movies or music are beautiful because their cultures determine a uniformity of aesthetic taste. Taste for both natural beauty and for the arts travel across cultures with great ease. Beethoven is adored in Japan. Peruvians love Japanese woodblock prints. Inca sculptures are regarded as treasures in British museums, while Shakespeare is translated into every major language of the Earth. Or just think about American jazz or American movies -- they go everywhere. There are many differences among the arts, but there are also universal, cross-cultural aesthetic pleasures and values.

How can we explain this universality? The best answer lies in trying to reconstruct a Darwinian evolutionary history of our artistic and aesthetic tastes. We need to reverse-engineer our present artistic tastes and preferences and explain how they came to be engraved in our minds by the actions of both our prehistoric, largely pleistocene environments, where we became fully human, but also by the social situations in which we evolved. This reverse engineering can also enlist help from the human record preserved in prehistory. I mean fossils, cave paintings and so forth. And it should take into account what we know of the aesthetic interests of isolated hunter-gatherer bands that survived into the 19th and the 20th centuries.

Now, I personally have no doubt whatsoever that the experience of beauty, with its emotional intensity and pleasure, belongs to our evolved human psychology. The experience of beauty is one component in a whole series of Darwinian adaptations. Beauty is an adaptive effect, which we extend and intensify in the creation and enjoyment of works of art and entertainment. As many of you will know, evolution operates by two main primary mechanisms. The first of these is natural selection -- that's random mutation and selective retention -- along with our basic anatomy and physiology -- the evolution of the pancreas or the eye or the fingernails. Natural selection also explains many basic revulsions, such as the horrid smell of rotting meat, or fears, such as the fear of snakes or standing close to the edge of a cliff. Natural selection also explains pleasures -- sexual pleasure, our liking for sweet, fat and proteins, which in turn explains a lot of popular foods, from ripe fruits through chocolate malts and barbecued ribs.

The other great principle of evolution is sexual selection, and it operates very differently. The peacock's magnificent tail is the most famous example of this. It did not evolve for natural survival. In fact, it goes against natural survival. No, the peacock's tail results from the mating choices made by peahens. It's quite a familiar story. It's women who actually push history forward. Darwin himself, by the way, had no doubts that the peacock's tail was beautiful in the eyes of the peahen. He actually used that word. Now, keeping these ideas firmly in mind, we can say that the experience of beauty is one of the ways that evolution has of arousing and sustaining interest or fascination, even obsession, in order to encourage us toward making the most adaptive decisions for survival and reproduction. Beauty is nature's way of acting at a distance, so to speak. I mean, you can't expect to eat an adaptively beneficial landscape. It would hardly do to eat your baby or your lover. So evolution's trick is to make them beautiful, to have them exert a kind of magnetism to give you the pleasure of simply looking at them.

Consider briefly an important source of aesthetic pleasure, the magnetic pull of beautiful landscapes. People in very different cultures all over the world tend to like a particular kind of landscape, a landscape that just happens to be similar to the pleistocene savannas where we evolved. This landscape shows up today on calendars, on postcards, in the design of golf courses and public parks and in gold-framed pictures that hang in living rooms from New York to New Zealand. It's a kind of Hudson River school landscape featuring open spaces of low grasses interspersed with copses of trees. The trees, by the way, are often preferred if they fork near the ground, that is to say, if they're trees you could scramble up if you were in a tight fix. The landscape shows the presence of water directly in view, or evidence of water in a bluish distance, indications of animal or bird life as well as diverse greenery and finally -- get this -- a path or a road, perhaps a riverbank or a shoreline, that extends into the distance, almost inviting you to follow it. This landscape type is regarded as beautiful, even by people in countries that don't have it. The ideal savanna landscape is one of the clearest examples where human beings everywhere find beauty in similar visual experience.

But, someone might argue, that's natural beauty. How about artistic beauty? Isn't that exhaustively cultural? No, I don't think it is. And once again, I'd like to look back to prehistory to say something about it. It is widely assumed that the earliest human artworks are the stupendously skillful cave paintings that we all know from Lascaux and Chauvet. Chauvet caves are about 32,000 years old, along with a few small, realistic sculptures of women and animals from the same period. But artistic and decorative skills are actually much older than that. Beautiful shell necklaces that look like something you'd see at an arts and crafts fair, as well as ochre body paint, have been found from around 100,000 years ago.

But the most intriguing prehistoric artifacts are older even than this. I have in mind the so-called Acheulian hand axes. The oldest stone tools are choppers from the Olduvai Gorge in East Africa. They go back about two-and-a-half-million years. These crude tools were around for thousands of centuries, until around 1.4 million years ago when Homo erectus started shaping single, thin stone blades, sometimes rounded ovals, but often in what are to our eyes an arresting, symmetrical pointed leaf or teardrop form. These Acheulian hand axes -- they're named after St. Acheul in France, where finds were made in 19th century -- have been unearthed in their thousands, scattered across Asia, Europe and Africa, almost everywhere Homo erectus and Homo ergaster roamed. Now, the sheer numbers of these hand axes shows that they can't have been made for butchering animals. And the plot really thickens when you realize that, unlike other pleistocene tools, the hand axes often exhibit no evidence of wear on their delicate blade edges. And some, in any event, are too big to use for butchery. Their symmetry, their attractive materials and, above all, their meticulous workmanship are simply quite beautiful to our eyes, even today.

So what were these ancient -- I mean, they're ancient, they're foreign, but they're at the same time somehow familiar. What were these artifacts for? The best available answer is that they were literally the earliest known works of art, practical tools transformed into captivating aesthetic objects, contemplated both for their elegant shape and their virtuoso craftsmanship. Hand axes mark an evolutionary advance in human history -- tools fashioned to function as what Darwinians call "fitness signals" -- that is to say, displays that are performances like the peacock's tail, except that, unlike hair and feathers, the hand axes are consciously cleverly crafted. Competently made hand axes indicated desirable personal qualities -- intelligence, fine motor control, planning ability, conscientiousness and sometimes access to rare materials. Over tens of thousands of generations, such skills increased the status of those who displayed them and gained a reproductive advantage over the less capable. You know, it's an old line, but it has been shown to work -- "Why don't you come up to my cave, so I can show you my hand axes?"

(Laughter)

Except, of course, what's interesting about this is that we can't be sure how that idea was conveyed, because the Homo erectus that made these objects did not have language. It's hard to grasp, but it's an incredible fact. This object was made by a hominid ancestor, Homo erectus or Homo ergaster, between 50,000 and 100,000 years before language. Stretching over a million years, the hand axe tradition is the longest artistic tradition in human and proto-human history. By the end of the hand axe epic, Homo sapiens -- as they were then called, finally -- were doubtless finding new ways to amuse and amaze each other by, who knows, telling jokes, storytelling, dancing, or hairstyling. Yes, hairstyling -- I insist on that.

For us moderns, virtuoso technique is used to create imaginary worlds in fiction and in movies, to express intense emotions with music, painting and dance. But still,one fundamental trait of the ancestral personality persists in our aesthetic cravings: the beauty we find in skilled performances. From Lascaux to the Louvre to Carnegie Hall, human beings have a permanent innate taste for virtuoso displays in the arts. We find beauty in something done well.

So the next time you pass a jewelry shop window displaying a beautifully cut teardrop-shaped stone, don't be so sure it's just your culture telling you that that sparkling jewel is beautiful. Your distant ancestors loved that shape and found beauty in the skill needed to make it, even before they could put their love into words. Is beauty in the eye of the beholder? No, it's deep in our minds. It's a gift handed down from the intelligent skills and rich emotional lives of our most ancient ancestors. Our powerful reaction to images, to the expression of emotion in art, to the beauty of music, to the night sky, will be with us and our descendants for as long as the human race exists.

Thank you.

(Applause)

この場でみなさんに 私の大好きなテーマである 美についてお話できるのをうれしく思います 私は美の哲学 美学を 生業としています 美という体験は何なのか 美について確かに言えることは何か 人は美を理解しようとして いかに道に迷うかといったことを 知的、哲学的、心理学的に解明しようとしています 美というのは恐ろしく込み入ったテーマであり 私たちが美しいと呼んでいるものには 非常に大きな幅があります いかにバラエティに富んでいることか 赤ちゃんの顔 ベルリオーズの「イタリアのハロルド」 「オズの魔法使い」のような映画 チェーホフの戯曲 中部カリフォルニアの風景 北斎の富士山の絵 「ばらの騎士」 ワールドカップサッカーの試合での 見事な決勝ゴール ファン・ゴッホの「星月夜」 ジェーン・オースティンの小説 スクリーンを踊り回るフレッド・アステア この短いリストの中にも 人間 自然の風景 美術作品 巧みなパフォーマンスが 含まれています このリストにあるすべてに 共通する美を説明するのでさえ 簡単ではありません

しかしそれでも 私たちが これまで手にした 最も強力な美の理論の片鱗は お伝えできると思います その理論の主は 美学者や ポストモダンの美術理論家や 芸術批評の大家 ではありません この理論を唱えたのは フジツボや ミミズや ハトの育種に関する専門家 皆さんご存じの チャールズ・ダーウィンなのです もちろん多くの人は「美とは何か」という 質問に対する正しい答えを 知っていると思っています 「美は見る人の目の中にある」 心を動かされるものが美しいのです あるいは ある人々 特に学者が好んで言うのは 「美は文化的に条件付けられた 目の中にある」ということです 絵画や映画や音楽が美しいのは 文化が美の基準を 規定しているためだと 多くの人は思っています 自然の美も芸術の美も 文化を超えて 易々と伝わります ベートーベンは日本で愛されており ペルー人は 日本の木版画を愛し インカの彫刻は 大英博物館の宝となっています そしてシェークスピアは 地上の主要なあらゆる言語へと翻訳され アメリカのジャズや映画は 世界にあまねく 行き渡っています 個々の芸術には多くの違いがありますが 文化の違いを超えた 普遍的な 美の喜びや 価値があるのです

この普遍性は どう説明できるのでしょう? 最良の答えは 芸術的・美的な嗜好が進化してきた 歴史を再構築することから得られます 私たちの現在の芸術的な 美意識や好みの起源を辿って それがいかに私たちの心に 刻まれるようになったのかを 解明する必要があります 有史以前の 私たちが今のような人間になった 更新世の環境と 人類が進化してきた社会的状況の 両方に目を向けましょう この探求にはまた 有史以前の記録も 助けになるでしょう 出土品や 洞窟壁画などです それに19世紀から20世紀まで 孤立して存続していた 狩猟採集部族の 美的関心についての知識も 考慮に入れるべきでしょう

私は個人的には 強い感情や喜びを伴う 美の体験は何であれ 人類の心理的な進化に 属すものだと確信しています 美の体験は 一連の進化的適応の中の 1つの要素なのです 美は適応のための作用であり 芸術や娯楽作品の 創作や享受を通して 拡張され 強められてきたのです 皆さんご存じのように 進化は2つの主要なメカニズムで動いています 第一は自然淘汰で ランダムな突然変異と選択的な保存により 基本的な解剖・生理学的形質が進化しました 膵臓だとか目だとか爪といったものです 自然淘汰は 腐った肉の ひどい臭いに対する嫌悪とか ヘビや 断崖の縁に立つことへの 恐怖の説明にもなり また喜びも 自然淘汰で説明できます 性的な喜びや 甘いもの、脂肪、タンパク質に対する好みもそう これは人気のある食べ物が好まれる理由なのです 熟した果物や チョコレートモルト それに あばら肉のバーベキュー

進化のもう1つの大きな原理は 性淘汰で これは非常に違った働き方をします クジャクの見事な尾羽は この最も有名な例でしょう あれは生存のための助けにはなりません 実際にはむしろ生存の邪魔になります クジャクの羽は 雌による選択の 結果なのです 歴史を実際に推し進めていたのは 女性だったという 聞いたことのあるような話ですね ダーウィン自身 クジャクの羽は雌の目に 美しいものだと考えていました 実際に「美」という言葉を使っています このアイデアをしっかり頭に刻んでおくと 美の体験というのも 生存や繁殖に 最も適した選択を行うよう 仕向けるために 関心や 魅惑や さらには執着までを 引き起こし 持続させる 進化の手段であることがわかります 美というのは 言ってみれば 自然が遠くから力を働かせる 方法なのです 適応に有利な風景は 食べ物みたいに直接的対象ではありません 子供や恋人というのも おおよそそうです だから進化は美しくするという トリックを使うのです 単に見ているだけで喜びを感じるような 魅力を持たせるのです

美的な喜びの重要な源の1つである 美しい風景の魅力について ちょっと考えてみましょう 世界の様々な 異なる文化の人々に ある共通の風景を好む傾向があります それは人類が進化してきた 更新世のサバンナの風景と似ています この風景が今日 カレンダーになり 絵はがきになり ゴルフコースや公園の設計に使われ ニューヨークでも ニュージーランドでも 金の額縁に入れて リビングに飾られています ハドソン・リバー派の絵のような風景で 開けていて 丈の低い草が生え 林が点在しています 木は 地面に近いところで 枝分かれしているのが好まれます 苦境に陥ったときに よじ登れるような木です この風景の中か あるいは青く霞んだ彼方に 水の存在が示され 豊かな緑とともに 動物や鳥がいます そして最後に 遠くへと続く 道があります あるいは川岸か海岸線かもしれません 彼方へと続いていて 辿るようにと誘っているかのようです こういう風景は美しいと見なされています このような風景を 持たない国の人々にもです 理想的なサバンナの風景は 至る所の人類が 視覚的体験として 同じように美を認める 最も明確な例の1つです

しかしこれは自然の美の話であって 芸術の美は まったく文化的なものだと 言う人がいるかもしれません 私はそうは思いません 再び有史以前に 目を向けてみましょう 人類のもっとも早い時期の 芸術作品として 広く認められているのは ラスコーやショーヴェの 見事な洞窟壁画でしょう ショーヴェ洞窟は 約3万2千年前のもので 同じ時期には 小さく写実的な 女性や動物の彫像も作られています しかし芸術的・装飾的なスキル自体は 実際それよりずっと以前まで遡ります 今日手工芸フェアで目にするような 美しい貝のネックレスや 黄土色のボディペイントで 10万年ほど前のものが 見つかっています

しかし有史以前で最も目を引かれる工芸品は それよりも遙かに古いものです 私が考えているのは アシュールの手斧と呼ばれているものです 最も古い石器は 東アフリカにある オルドヴァイ渓谷で見つかった包丁です 約250万年前のものです この粗い作りの道具は 何十万年にも渡って使われ続けましたが 約140万年前になって ホモ・エレクトゥスが 薄く鋭い石の刃を 作るようになりました 楕円形が多いですが それは時に 私たちが見ても 魅力的に感じる 対称的でとがった 葉っぱや涙の形をしています これらアシュールの手斧は それが19世紀に発見されたフランスの サン・タシュールから名付けられたのですが 何千という数のものが アジアやヨーロッパやアフリカで発掘され ホモ・エレクトゥスやホモ・エルガステルが放浪していた ほとんどあらゆる場所で見つかっています これらの手斧の数だけを見ても 単に動物の解体だけのために 作られたのではないことを思わせます 更新世の他の道具とは違い 時に全く摩耗していない 繊細な刃を持った 手斧が見つかることも この点を補強します 中には大きすぎて 使えそうにないものまであります その対称性 魅力的な素材 そして何よりも 繊細な細工は 今日の私たちの目から見ても まったく美しいものです

これらは遙か昔の 遠い存在ですが 同時に何か 馴染みがあるようにも感じられます これらの作品は何のために作られたのでしょう? 最良の答えはたぶん それは文字通り 最初の芸術作品であり 実用的な道具が エレガントな形や名人芸的な細工によって 魅力的で美しいオブジェへと 変わったということです 手斧は 人類の進化を示しています これはダーウィン主義者が言う 適応度の信号として 機能する道具であり クジャクの羽同様に パフォーマンスのためのものですが ただ羽と違うのは 手斧は意識して 巧みに作られたということです 出来の良い手斧は 作り手の優れた資質を示します 知性 器用さ 計画能力 細心さ それに希少資源を入手できる というのもあるかもしれません 何万世代にも渡って そのようなスキルはそれを持つ者の ステータスを上げ スキルのないものに対して 子孫を残す上で利点となったことでしょう これは古くさい台詞ですが 機能することが示されています 「うちの洞窟に来ない? 僕の手斧を見せてあげるよ」

(笑)

興味深いのは このアイデアが どのように伝えられたかということです なぜなら これらを作った ホモ・エレクトゥスは 言語を持っていなかったからです 理解しがたいことですが 驚くべき事実です これらのものを作ったのは ヒトの祖先の ホモ・エレクトゥスやホモ・エルガステルで 言語が現れる5万年から 10万年前のことです 手斧の伝統は 百万年以上に渡る ヒトと古人類の歴史における 最も長い芸術的伝統なのです 手斧の時代の終わりに ホモ・サピエンスが ようやく 互いを楽しませ 感心させる新しい方法を 見つけるようになりました ジョークや 物語、ダンス、ヘアスタイル ヘアスタイルだってそうなのです

私たち現代人においては 名人芸的な技術は フィクションや映画で 想像の世界を生み出したり 音楽や絵やダンスによって 強い感情を表現するのに使われています しかし依然として 私たちの美的な欲求には 祖先の性格の 痕跡が残っており それは巧みなパフォーマンスに 美を見出すことです ラスコーからルーブルや カーネギーホールまで 人類は 芸術における名人芸に対して 変わらない深い愛情を持ち続けてきました 見事になされるものに対して 美を感じるのです

だからこの次に 見事にカットされた涙の形をした 宝石が飾られた宝石店の ウィンドウの前を通り過ぎるとき その輝く宝石を美しいと思わせるのは 単に文化なのだとは 思わないことです 皆さんの遠い祖先もその形を愛し それを作るのに必要なスキルに美を見出していたのです 愛を言葉にできるようになる ずっと以前にです 美は見る人の目の中にあるのでしょうか? いいえ 私たちの心の奥深くにあるのです これは賜物であり 私たちの古い祖先の 知的スキルと豊かな感情生活から 受け継いだものなのです イメージや 芸術における感情表現や 美しい音楽や 夜空に対する私たちの強い反応は 人類という種が続く限り 私たちの子孫へと受け継がれていくことでしょう

どうもありがとうございました

(拍手)

品詞分類

- 主語

- 動詞

- 助動詞

- 準動詞

- 関係詞等

TED 日本語

TED Talks

関連動画

アーティストは経済にどう貢献し、私たちは彼らをどう支えられるか?ハディ・エルデベック

2018.04.09

コンテンツを流行らせる要素とは?ダオ・グエン

2018.01.08

私がアートを制作するのは、伝統を受け継ぐタイムカプセルを作るためケイラ・ブリエット

2017.12.08

ニューヨーカー誌、象徴的な表紙イラストの舞台裏フランソワーズ・ムーリー

2017.08.17

とらえ難い心情を表す素敵な新語の数々ジョン・ケーニック

2017.03.31

2千本のおくやみ記事から学んだことラックス・ナラヤン

2017.03.23

メロドラマが教えてくれる4つの大げさな人生訓ケイト・アダムス

2017.01.03

音楽がもたらしたコンピューターの発明スティーヴン・ジョンソン

2016.12.09

Ideas worth dating -- デートする価値のあるアイデアレイン・ウィルソン

2016.10.30

購読解除の苦悩!ジェイムズ・ヴィーチ

2016.09.27

コスプレへの愛アダム・サヴェッジ

2016.08.23

「アンチ」を科学的に分類してみようネギン・ファルサド

2016.07.05

データで描く、示唆に富む肖像画ルーク・デュボワ

2016.05.19

詐欺メール 返信すると どうなるかジェイムズ・ヴィーチ

2016.02.01

世界中の国の本を1冊ずつ読んでいく私の1年アン・モーガン

2015.12.21

日常の音に隠された思いがけない美とはメクリト・ハデロ

2015.11.10

洋楽 おすすめ

RECOMMENDS

洋楽歌詞

ダイナマイトビーティーエス

洋楽最新ヒット2020.08.20

ディス・イズ・ミーグレイテスト・ショーマン・キャスト

洋楽人気動画2018.01.11

グッド・ライフGイージー、ケラーニ

洋楽人気動画2017.01.27

ホワット・ドゥ・ユー・ミーン?ジャスティン・ビーバー

洋楽人気動画2015.08.28

ファイト・ソングレイチェル・プラッテン

洋楽人気動画2015.05.19

ラヴ・ミー・ライク・ユー・ドゥエリー・ゴールディング

洋楽人気動画2015.01.22

アップタウン・ファンクブルーノ・マーズ、マーク・ロンソン

洋楽人気動画2014.11.20

ブレイク・フリーアリアナ・グランデ

洋楽人気動画2014.08.12

ハッピーファレル・ウィリアムス

ポップス2014.01.08

カウンティング・スターズワンリパブリック

ロック2013.05.31

ア・サウザンド・イヤーズクリスティーナ・ペリー

洋楽人気動画2011.10.26

ユー・レイズ・ミー・アップケルティック・ウーマン

洋楽人気動画2008.05.30

ルーズ・ユアセルフエミネム

洋楽人気動画2008.02.21

ドント・ノー・ホワイノラ・ジョーンズ

洋楽人気動画2008.02.15

オンリー・タイムエンヤ

洋楽人気動画2007.10.03

ミス・ア・シングエアロスミス

ロック2007.08.18

タイム・トゥ・セイ・グッバイサラ・ブライトマン

洋楽人気動画2007.06.08

シェイプ・オブ・マイ・ハートスティング

洋楽人気動画2007.03.18

ウィ・アー・ザ・ワールド(U.S.A. フォー・アフリカ)マイケル・ジャクソン

洋楽人気動画2006.05.14

ホテル・カリフォルニアイーグルス

ロック2005.07.06