TED日本語

TED Talks(英語 日本語字幕付き動画)

TED日本語 - デイヴィッド・オートー: 自動化で人間の仕事はなくなるのか?

TED Talks

自動化で人間の仕事はなくなるのか?

Will automation take away all our jobs?

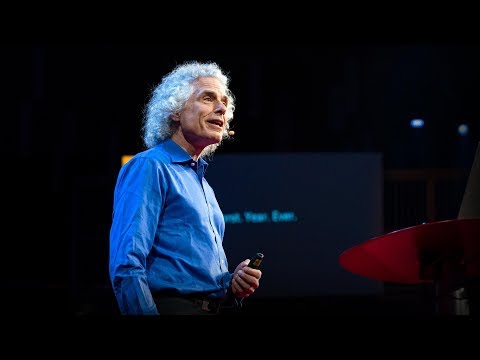

デイヴィッド・オートー

David Autor

内容

これはあまり耳にすることのないパラドックスですが、1世紀に渡り人間に代わって仕事をする機械が作られてきたにもかかわらず、アメリカで仕事に就く成人人口の割合は過去125年の間増え続けているのです。どうして人間の労働が余計になったり、人間のスキルが廃れたりしないのでしょう?仕事の未来に関するこの講演で、経済学者のデイヴィッド・オートーが、なぜ未だこんなにも多くの仕事があるのかを問い、驚きと希望に満ちた答えを出します。

字幕

SCRIPT

Script

Here's a startling fact: in the 45 years since the introduction of the automated teller machine, those vending machines that dispense cash, the number of human bank tellers employed in the United States has roughly doubled, from about a quarter of a million to a half a million. A quarter of a million in 1970 to about a half a million today, with 100,000 added since the year 2000.

These facts, revealed in a recent book by Boston University economist James Bessen, raise an intriguing question: what are all those tellers doing, and why hasn't automation eliminated their employment by now? If you think about it, many of the great inventions of the last 200 years were designed to replace human labor. Tractors were developed to substitute mechanical power for human physical toil. Assembly lines were engineered to replace inconsistent human handiwork with machine perfection. Computers were programmed to swap out error-prone, inconsistent human calculation with digital perfection. These inventions have worked. We no longer dig ditches by hand, pound tools out of wrought iron or do bookkeeping using actual books. And yet, the fraction of US adults employed in the labor market is higher now in 2016 than it was 125 years ago, in 1890, and it's risen in just about every decade in the intervening 125 years.

This poses a paradox. Our machines increasingly do our work for us. Why doesn't this make our labor redundant and our skills obsolete? Why are there still so many jobs?

(Laughter)

I'm going to try to answer that question tonight, and along the way, I'm going to tell you what this means for the future of work and the challenges that automation does and does not pose for our society.

Why are there so many jobs? There are actually two fundamental economic principles at stake. One has to do with human genius and creativity. The other has to do with human insatiability, or greed, if you like. I'm going to call the first of these the O-ring principle, and it determines the type of work that we do. The second principle is the never-get-enough principle, and it determines how many jobs there actually are.

Let's start with the O-ring. ATMs, automated teller machines, had two countervailing effects on bank teller employment. As you would expect, they replaced a lot of teller tasks. The number of tellers per branch fell by about a third. But banks quickly discovered that it also was cheaper to open new branches, and the number of bank branches increased by about 40 percent in the same time period. The net result was more branches and more tellers. But those tellers were doing somewhat different work. As their routine, cash-handling tasks receded, they became less like checkout clerks and more like salespeople, forging relationships with customers, solving problems and introducing them to new products like credit cards, loans and investments: more tellers doing a more cognitively demanding job. There's a general principle here. Most of the work that we do requires a multiplicity of skills, and brains and brawn, technical expertise and intuitive mastery, perspiration and inspiration in the words of Thomas Edison. In general, automating some subset of those tasks doesn't make the other ones unnecessary. In fact, it makes them more important. It increases their economic value.

Let me give you a stark example. In 1986, the space shuttle Challenger exploded and crashed back down to Earth less than two minutes after takeoff. The cause of that crash, it turned out, was an inexpensive rubber O-ring in the booster rocket that had frozen on the launchpad the night before and failed catastrophically moments after takeoff. In this multibillion dollar enterprise that simple rubber O-ring made the difference between mission success and the calamitous death of seven astronauts. An ingenious metaphor for this tragic setting is the O-ring production function, named by Harvard economist Michael Kremer after the Challenger disaster. The O-ring production function conceives of the work as a series of interlocking steps, links in a chain. Every one of those links must hold for the mission to succeed. If any of them fails, the mission, or the product or the service, comes crashing down. This precarious situation has a surprisingly positive implication, which is that improvements in the reliability of any one link in the chain increases the value of improving any of the other links. Concretely, if most of the links are brittle and prone to breakage, the fact that your link is not that reliable is not that important. Probably something else will break anyway. But as all the other links become robust and reliable, the importance of your link becomes more essential. In the limit, everything depends upon it. The reason the O-ring was critical to space shuttle Challenger is because everything else worked perfectly. If the Challenger were kind of the space era equivalent of Microsoft Windows 2000 --

(Laughter)

the reliability of the O-ring wouldn't have mattered because the machine would have crashed.

(Laughter)

Here's the broader point. In much of the work that we do, we are the O-rings. Yes, ATMs could do certain cash-handling tasks faster and better than tellers, but that didn't make tellers superfluous. It increased the importance of their problem-solving skills and their relationships with customers. The same principle applies if we're building a building, if we're diagnosing and caring for a patient, or if we are teaching a class to a roomful of high schoolers. As our tools improve, technology magnifies our leverage and increases the importance of our expertise and our judgment and our creativity.

And that brings me to the second principle: never get enough. You may be thinking, OK, O-ring, got it, that says the jobs that people do will be important. They can't be done by machines, but they still need to be done. But that doesn't tell me how many jobs there will need to be. If you think about it, isn't it kind of self-evident that once we get sufficiently productive at something, we've basically worked our way out of a job? In 1900,40 percent of all US employment was on farms. Today, it's less than two percent. Why are there so few farmers today? It's not because we're eating less.

(Laughter)

A century of productivity growth in farming means that now, a couple of million farmers can feed a nation of 320 million. That's amazing progress, but it also means there are only so many O-ring jobs left in farming. So clearly, technology can eliminate jobs. Farming is only one example. There are many others like it. But what's true about a single product or service or industry has never been true about the economy as a whole. Many of the industries in which we now work -- health and medicine, finance and insurance, electronics and computing -- were tiny or barely existent a century ago. Many of the products that we spend a lot of our money on -- air conditioners, sport utility vehicles, computers and mobile devices -- were unattainably expensive, or just hadn't been invented a century ago. As automation frees our time, increases the scope of what is possible, we invent new products, new ideas, new services that command our attention, occupy our time and spur consumption. You may think some of these things are frivolous -- extreme yoga, adventure tourism, Pokemon GO -- and I might agree with you. But people desire these things, and they're willing to work hard for them. The average worker in 2015 wanting to attain the average living standard in 1915 could do so by working just 17 weeks a year,one third of the time. But most people don't choose to do that. They are willing to work hard to harvest the technological bounty that is available to them. Material abundance has never eliminated perceived scarcity. In the words of economist Thorstein Veblen, invention is the mother of necessity.

Now ... So if you accept these two principles, the O-ring principle and the never-get-enough principle, then you agree with me. There will be jobs. Does that mean there's nothing to worry about? Automation, employment, robots and jobs -- it'll all take care of itself? No. That is not my argument. Automation creates wealth by allowing us to do more work in less time. There is no economic law that says that we will use that wealth well, and that is worth worrying about. Consider two countries, Norway and Saudi Arabia. Both oil-rich nations, it's like they have money spurting out of a hole in the ground.

(Laughter)

But they haven't used that wealth equally well to foster human prosperity, human prospering. Norway is a thriving democracy. By and large, its citizens work and play well together. It's typically numbered between first and fourth in rankings of national happiness. Saudi Arabia is an absolute monarchy in which many citizens lack a path for personal advancement. It's typically ranked 35th among nations in happiness, which is low for such a wealthy nation. Just by way of comparison, the US is typically ranked around 12th or 13th. The difference between these two countries is not their wealth and it's not their technology. It's their institutions. Norway has invested to build a society with opportunity and economic mobility. Saudi Arabia has raised living standards while frustrating many other human strivings. Two countries, both wealthy, not equally well off.

And this brings me to the challenge that we face today, the challenge that automation poses for us. The challenge is not that we're running out of work. The US has added 14 million jobs since the depths of the Great Recession. The challenge is that many of those jobs are not good jobs, and many citizens can not qualify for the good jobs that are being created. Employment growth in the United States and in much of the developed world looks something like a barbell with increasing poundage on either end of the bar. On the one hand, you have high-education, high-wage jobs like doctors and nurses, programmers and engineers, marketing and sales managers. Employment is robust in these jobs, employment growth. Similarly, employment growth is robust in many low-skill, low-education jobs like food service, cleaning, security, home health aids. Simultaneously, employment is shrinking in many middle-education, middle-wage, middle-class jobs, like blue-collar production and operative positions and white-collar clerical and sales positions. The reasons behind this contracting middle are not mysterious. Many of those middle-skill jobs use well-understood rules and procedures that can increasingly be codified in software and executed by computers. The challenge that this phenomenon creates, what economists call employment polarization, is that it knocks out rungs in the economic ladder, shrinks the size of the middle class and threatens to make us a more stratified society. On the one hand, a set of highly paid, highly educated professionals doing interesting work, on the other, a large number of citizens in low-paid jobs whose primary responsibility is to see to the comfort and health of the affluent. That is not my vision of progress, and I doubt that it is yours.

But here is some encouraging news. We have faced equally momentous economic transformations in the past, and we have come through them successfully. In the late 1800s and early 1900s, when automation was eliminating vast numbers of agricultural jobs -- remember that tractor? -- the farm states faced a threat of mass unemployment, a generation of youth no longer needed on the farm but not prepared for industry. Rising to this challenge, they took the radical step of requiring that their entire youth population remain in school and continue their education to the ripe old age of 16. This was called the high school movement, and it was a radically expensive thing to do. Not only did they have to invest in the schools, but those kids couldn't work at their jobs. It also turned out to be one of the best investments the US made in the 20th century. It gave us the most skilled, the most flexible and the most productive workforce in the world. To see how well this worked, imagine taking the labor force of 1899 and bringing them into the present. Despite their strong backs and good characters, many of them would lack the basic literacy and numeracy skills to do all but the most mundane jobs. Many of them would be unemployable.

What this example highlights is the primacy of our institutions, most especially our schools, in allowing us to reap the harvest of our technological prosperity.

It's foolish to say there's nothing to worry about. Clearly we can get this wrong. If the US had not invested in its schools and in its skills a century ago with the high school movement, we would be a less prosperous, a less mobile and probably a lot less happy society. But it's equally foolish to say that our fates are sealed. That's not decided by the machines. It's not even decided by the market. It's decided by us and by our institutions.

Now, I started this talk with a paradox. Our machines increasingly do our work for us. Why doesn't that make our labor superfluous, our skills redundant? Isn't it obvious that the road to our economic and social hell is paved with our own great inventions?

History has repeatedly offered an answer to that paradox. The first part of the answer is that technology magnifies our leverage, increases the importance, the added value of our expertise, our judgment and our creativity. That's the O-ring. The second part of the answer is our endless inventiveness and bottomless desires means that we never get enough, never get enough. There's always new work to do. Adjusting to the rapid pace of technological change creates real challenges, seen most clearly in our polarized labor market and the threat that it poses to economic mobility. Rising to this challenge is not automatic. It's not costless. It's not easy. But it is feasible. And here is some encouraging news. Because of our amazing productivity, we're rich. Of course we can afford to invest in ourselves and in our children as America did a hundred years ago with the high school movement. Arguably, we can't afford not to.

Now, you may be thinking, Professor Autor has told us a heartwarming tale about the distant past, the recent past, maybe the present, but probably not the future. Because everybody knows that this time is different. Right? Is this time different? Of course this time is different. Every time is different. On numerous occasions in the last 200 years, scholars and activists have raised the alarm that we are running out of work and making ourselves obsolete: for example, the Luddites in the early 1800s; US Secretary of Labor James Davis in the mid-1920s; Nobel Prize-winning economist Wassily Leontief in 1982; and of course, many scholars, pundits, technologists and media figures today.

These predictions strike me as arrogant. These self-proclaimed oracles are in effect saying, "If I can't think of what people will do for work in the future, then you, me and our kids aren't going to think of it either." I don't have the guts to take that bet against human ingenuity. Look, I can't tell you what people are going to do for work a hundred years from now. But the future doesn't hinge on my imagination. If I were a farmer in Iowa in the year 1900, and an economist from the 21st century teleported down to my field and said, "Hey, guess what, farmer Autor, in the next hundred years, agricultural employment is going to fall from 40 percent of all jobs to two percent purely due to rising productivity. What do you think the other 38 percent of workers are going to do?" I would not have said, "Oh, we got this. We'll do app development, radiological medicine, yoga instruction, Bitmoji."

(Laughter)

I wouldn't have had a clue. But I hope I would have had the wisdom to say, "Wow, a 95 percent reduction in farm employment with no shortage of food. That's an amazing amount of progress. I hope that humanity finds something remarkable to do with all of that prosperity."

And by and large, I would say that it has.

Thank you very much.

(Applause)

ひとつ驚くべき事実があります 45年前に ATM ― あの現金の自販機が 導入されて以来 アメリカで雇用されている 銀行窓口係の数は おおよそ2倍に 25万人から50万人に 増えていて 1970年に25万人だったのが 今では50万人 2000年以降だけでも 10万人増えているんです

ボストン大学の経済学者 ジェームズ・ベッセンが 最近出した本で 明らかにされたこの事実は 興味深い疑問を提起します その人たちは いったい何をやっているのか? なぜ自動化によって そういった仕事がなくならないのか? 考えてみれば 過去200年における 偉大な発明の多くは 人間の労働を 置き換えるためのものでした トラクターは人間の肉体労働を 機械の力で置き換えるものとして 作られました 組み立てラインは ムラのある人間の手作業を 機械の正確さで 置き換えるため考案されました コンピューターは 間違いの多い手計算を デジタルの完璧さで置き換えるべく 生み出されました これらの発明は大成功でした 私たちはもはや 手で溝を掘ることも 鍛鉄から道具を打ち出すことも 紙の帳面で簿記をすることも なくなりました それでも労働市場で雇用されている アメリカ成人の割合は 2016年の今 125年前の1890年よりも 高くなっており その間10年ごとに ほぼ上がり続けているのです

これはパラドックスを提起します 機械がますます人間に代わって 仕事をしている中で なぜ人間の労働が余計になったり 人間のスキルが廃れたりしないのか? どうしてまだ こんなに仕事があるのか?

(笑)

今宵はどうにかこの疑問に 答えようと思います その過程で それが仕事の未来に 対して持つ意味合い また自動化が 我々の社会に提起する問題 しない問題について 話したいと思います

なぜこんなに沢山の仕事があるのか? これには2つの基本的な 経済学原理が関わっています 1つは人間の才覚や 創造性に関するもので もう1つは人間の 飽くことを知らない どん欲さに関わるものです 1番目のものを 「Oリングの原理」と呼びましょう これは人間がする仕事の種類を 決めるものです 2番目の原理は 「足ることなしの原理」です これはどれだけ多くの仕事があるかを 決めるものです

Oリングの話から始めましょう ATM(現金自動預け払い機)には 銀行窓口係の雇用に対し 相殺する2つの効果がありました ご想像の通り それは多くの窓口係の作業を 代替することになり 支店あたりの窓口係の数は 3分の1減少しました しかしまた 銀行は新たに支店を開くコストが 安くなったことに気付き 同じ時期に 銀行の支店数は 40%増加しました 総数としては支店数とともに 窓口係の数も増えたのです しかし窓口係の仕事内容も 少し変わりました 日常の業務として 現金受渡の作業は減って 出納係よりは セールスマンのような仕事になりました 顧客との関係を築き 問題を解決し クレジットカードや ローンや 投資といった 新しい商品を紹介するようになったのです 窓口係の仕事は より頭脳が要求されるものになりました ここにはある一般原理が働いています 我々のする仕事の多くは 多様なスキルを必要とします 頭脳と筋力 ― 専門技術と経験の勘 エジソンの言うところの 努力とひらめき 通常そういった仕事の一部分を 自動化することで 他の部分は不要になりません むしろ その部分が より重要になります 経済的価値が高くなるのです

際だった例をお話ししましょう 1986年 スペースシャトル・ チャレンジャー号が 発射から2分もせずに爆発し 破片となって地上に落下しました 調査の結果分かったのは 爆発の原因は補助ロケットの 安価なゴム製Oリングにあり 前の夜に発射台で凍り付いて 発射直後に破滅的な故障を 来したということです この数十億ドル規模の事業において 単なるゴム製Oリングが 計画の成功と 7人の宇宙飛行士の悲惨な死とを 分けることになったのです 「Oリング生産関数」は この悲劇的な状況の 巧妙なメタファーとして ハーバードの経済学者 マイケル・クリーマーが チャレンジャー号事故の後に 名付けたものです Oリング生産関数は 仕事を 連動する 一連のステップ 鎖の輪として捉えるものです 計画の成功のためには すべての鎖の輪が機能する必要があります どれか1つでも壊れると 計画・製品・サービスの全体が 墜落することになります この危うい状況には 驚くほどポジティブな意味合いがあります 鎖の輪1つの信頼性を改善することは 他の鎖の輪を 改善することの価値を 高めるということです もしほとんどの鎖の輪が 脆く壊れやすいとしたら 自分の鎖の輪の 信頼性が高いかは さして重要ではありません どのみち どこかが壊れるでしょうから しかし他の鎖の輪がみんな 堅牢で高い信頼性があるとしたら 自分の鎖の輪の重要性は より本質的なものになります 究極的にはすべてが そこにかかることになります Oリングがチャレンジャー号にとって 要となったのは 他のすべてが完璧に 機能していたからです もしチャレンジャー号が 宇宙時代における Windows 2000のような 代物だったとしたら ―

(笑)

Oリングの信頼性など 問題にならなかったでしょう どうせクラッシュするんだから

(笑)

より一般的な話として言えるのは 我々のする仕事の大部分では 人間がOリングだということです ATMは確かに 現金受け払いの仕事を 窓口係より速くうまくこなしましたが それで窓口係が 不要になることはありませんでした むしろ窓口係の 問題解決力や 顧客との関係が 重要性を増したのです 同じ原理が 建物の建設や 患者の診察や手当 教室一杯の高校生への 授業などにも 当てはまります 道具が進歩し テクノロジーが 梃子として働くことで 人間の専門技術や 判断力や創造性が より重要になるのです

それが第2の原理に繋がります 「足ることなしの原理」です こうお思いかもしれません 「Oリングは分かった 人間の仕事が重要になる 機械にはできないが 必要な仕事があるんだと しかしそれは必要になる仕事の量については 何も言っていない」 何かについて 生産性が十二分に高くなったら その仕事から 人々が抜けていくのは 自明のことではないでしょうか? 1900年には アメリカの雇用の40%は 農業でした 今日では 2%未満です なぜ農業従事者が そんなに減ったんでしょう? みんなの食べる量が 減ったからではありません

(笑)

1世紀に渡る 農業生産性の向上により 今や2百万の農家が 3億2千万の国民を 食べさせられるようになったのです 驚くほどの進歩ですが これは農家に多くのOリング的な仕事が 残されたことも意味します だから確かにテクノロジーは 雇用を減らします 農業はその一例に過ぎません そういう例は他にも沢山あります しかし1個の製品・サービス・産業に当てはまることが 経済全体にも当てはまる わけではありません 現在人々の働く産業の多く 医療や健康 金融や保険 電子やITといったものは 100年前には存在しなかったか ごく小さなものでした 私たちが多くのお金を 使っている製品 エアコン SUV コンピューター 携帯機器といったものは 100年前にはとんでもなく高価か あるいは発明されても いませんでした 自動化により使える時間が増え 可能なことの範囲が広がり 新しい製品・アイデア・サービスが生み出され それが私たちの関心を引き 時間を占有し 消費を促すようになりました くだらないものが多いと 思うかもしれません 究極的なヨガ 冒険ツアー ポケモンGO・・・ それは認めます でも人々はそういったものを欲しがり そのために熱心に働きます 2015年の平均的な労働者が 1915年当時の平均的な 生活水準を得るためには 1年の3分の1 17週 働くだけでよいのです しかし多くの人は そうはしません 技術の賜を 手にするために 熱心に働くのです 物質的豊かさで 心理的な不足感が消えることはありません 経済学者ソースティン・ヴェブレンが 言うように 「発明は必要の母」なのです

さて この2つの原理 「Oリングの原理」と 「足ることなしの原理」を 認めてもらえるなら 仕事がなくならないのも うなずけるでしょう では心配することなど 何もないのでしょうか? 自動化 雇用 ロボット 仕事・・・ すべては自ずとうまくいくのでしょうか? いいえ それはまた別の話です 自動化は より少ない時間で 多くの仕事ができるようにすることで 富を生み出します しかし その富を 人間がうまく使うと保証する 経済法則はありません それは懸念すべき点です 2つの国 ノルウェーとサウジアラビアを 考えてみましょう どちらも石油のおかげで 豊かな国です 地面の穴から お金が 吹き出しているようなものです

(笑)

しかし両者が国民の繁栄のために その富を同じように使っている わけではありません ノルウェーは民主主義が うまくいっている国です 概ね国民は互いに うまくやっており 国民幸福度ランキングでは 大概1位から4位の間にいます サウジは絶対君主国で 多くの国民に栄達の道が 開かれてはいません 国民幸福度ランキングは 35位あたりで あのように豊かな国にしては 低い順位です 比較として アメリカがいるのは 12位か13位あたりです ノルウェーとサウジの違いは 豊かさでも テクノロジーでもなく 社会制度です ノルウェーは 機会が開かれていて 経済的移動性のある社会を 作るために投資してきました サウジでは 生活水準は上がりましたが 多くの国民は 不満を持っています 2つの国はどちらも豊かですが 同じようにうまくやっている わけではありません

これは我々が 今日直面する問題 自動化がもたらす問題を 思わせます 問題は仕事が なくなることではありません アメリカではグレート・リセッションの 最悪の時期から 雇用が1400万増えています 問題は 多くの職は 良い仕事でなく 多くの人には 新たに生まれる良い仕事に就ける スキルがないということです アメリカや その他の多くの 先進国における雇用の成長は 両端の重みが増していく バーベルのようです 一方には 高学歴・高収入の仕事 医師 看護師 プログラマー エンジニア マーケティングやセールスの 幹部社員といった仕事があります 雇用は堅調で成長しています 同様に 低スキル・低学歴の仕事もまた 雇用が増えています 食品サービス 清掃 警備 介護などです 他方で 中学歴・中収入な 中流の仕事が 縮小しています 工員や職人といった 労働者や 事務やセールスといった 事務職です この中間部の縮小は 不思議なことではありません そういった中間的スキルの仕事の多くは よく分かっている ルールや手順に従っており それがソフトウェア化されて コンピューターで 実行されるように なっているからです この現象が作り出すのは 経済学者が「雇用の二極化」 と呼ぶ問題で 経済の梯子の段が 取りのけられ 中間層が縮小し 社会の階層化が 進むということです 高収入・高学歴の 知的職業に就く人が 興味深い仕事をする一方で 多数の人は低収入の仕事をし その主な責務は 裕福な層が快適で 健康的であるように世話をすることなのです これは私の考える 進歩の姿ではありません 皆さんもそうでしょう

しかし心強い話もあります 私たちは過去に同じように大きな 経済的転換に直面しており それをうまく 切り抜けてきたのです 1800年代末から 1900年代初めにかけて 自動化によって農業の仕事が 大幅に減りました トラクターを思い出してください 農業州では大規模な失業の危機に 直面しました 1世代の若者達が 農場で必要とされなくなり 工業に従事できる準備もできていません この問題に対して 彼らは大胆な施策を取り 若い世代全体に 16歳まで学校に残り 教育を受けるよう 求めたのです これはハイスクール運動と呼ばれ 極めて高く付くことでした 学校への投資が 必要なだけでなく その若者達が 働けなくなるからです これはアメリカが20世紀にした 最良の投資であったことが 分かりました 世界でも最もスキルの高い 柔軟で生産的な労働力を 手にすることになったからです これがいかにうまくいったか理解するには 1899年の労働者を現代に 連れてきたところを想像するといいです いかに頑丈な体を持ち 良い性格をしていたとしても その多くは基本的な読み書きや 数理的なスキルを欠いていて 最も単純な仕事以外はできず 大部分が雇用不適格でしょう

この例が示しているのは 我々の制度 特に学校の優位性であり それが技術的繁栄の実りを 収穫できるようにしてくれたのです

何も心配することはない などと言うのは馬鹿げています 我々がやり方を間違うことは十分あり得ます もしアメリカが 1世紀前のハイスクール運動で 学校やスキルに 投資していなければ これほど繁栄はしておらず 経済移動性も低く ずっと不幸な社会になっていたでしょう しかし我々の運命は閉ざされている と言うのも愚かなことです 運命を決めるのは 機械ではなく マーケットでさえありません 運命を決めるのは 我々自身と 我々の制度なのです

私はパラドックスから 話を始めました 機械がますます人間の仕事を するようになっているのに どうして人間の労働やスキルが 余分なものにならないのか? 経済的・社会的な地獄への道は 我々自身の偉大な発明によって 敷かれているのは 自明なことではないのか?

歴史はこのパラドックスに 繰り返し答えてきました 答えの1つは テクノロジーが梃子として働き 人間の専門知識 判断力 創造性の 付加価値や重要性を 高めるということ Oリングです もう1つの答えは 人間の尽きることのない創意と 果てなき欲求のため 決して満ち足りることが ないということ 常に新たな仕事があるのです 技術が変化する速さへの対応は 難しい問題を生み出し そのことは 労働市場の二極化や それが経済的移動性を脅かす様に 見て取れます この困難を越えることは 自動的に出来ることでも コストなしにできることでもなく 容易ではありませんが 可能なことです そして明るい話もあります 驚くべき生産性のお陰で 我々は豊かです アメリカが100年前に ハイスクール運動でしたように 我々自身や子供達に投資することは もちろん可能です むしろ しないことは 許されないでしょう

こう思っているかもしれません オートー先生は 明るい話を 遠い昔や 少し前や 現在については しているかもしれないけど 未来のことは言っていない 今回が違うことは みんな知っているから 今回は違うんですよね? もちろん今回は違います 毎回違っているのです 過去200年間に 数え切れないくらい 学者や活動家達が 警告してきました 仕事がなくなり 我々は用済みになると たとえばラッダイトが 1800年代初めに 米国労働長官ジェームス・デイヴィスが 1920年代半ばに ノーベル賞経済学者ワシリー・レオンチェフが 1982年に言っています そしてもちろん 現在の多くの学者 評論家 科学技術者 マスメディアの人々が言っています

そのような予言は 私には傲慢に思えます そういった自称予言者達は 実質的にこう言っているのです 「人々が将来どんな仕事をするのか 私に考え付かないなら 世の人々にも 子孫達にも 考え付かないだろう」 人類の創意に対して そのような賭けをする肝っ玉は 私にはありません 何百年先に人々が どんな仕事をしているか 私には分かりません しかし未来は私の想像力に かかっているわけではありません 私が1900年の アイオワ州の農民で 21世紀から経済学者が 私の畑にテレポートしてきて言ったとします 「ねえ お百姓のオートーさん この先100年の 生産性向上によって 農業雇用は40%から 2%に減るんだよ 他の38%の人たちは 何を仕事にしていると思うね?」 私はたぶん こうは言わないでしょう 「ああ そりゃアプリ開発とか 放射線医療とか ヨガのインストラクターとか 絵文字デザインとかかな」

(笑)

私には見当が付かないでしょう しかし こう言える知恵が あればと思います 「すごいね 農業人口が95%減って 食糧不足にならないなんて すごい進歩だ その繁栄によって 人類が何かすごいことを やってくれることを望むよ」

そして概ねそうなっていると 私は思います

ありがとうございました

(拍手)

品詞分類

- 主語

- 動詞

- 助動詞

- 準動詞

- 関係詞等

TED 日本語

TED Talks

関連動画

実証実験が示す週4日勤務制の恩恵ジュリエット・ショアー

おすすめ 12022.05.27

経済的価値とは何か、そして誰がそれを生み出すのか?マリアナ・マッツカート

2020.01.10

教師のこころの健康をどうすればサポートできるかシドニー・ジェンセン

2019.12.13

資本主義の不都合な秘密と進むべき道ニック・ハノーアー

2019.10.18

新しい言語を学ぶ秘訣 - TED Talkリディア・マホヴァ

2019.01.24

人口が100億人に達する地球でどう生き延びるか?チャールズ・C・マン

2018.11.16

漫画は教室にふさわしい | TED Talkジーン・ヤン

2018.06.15

健全な経済は成長ではなく繁栄を目指しデザインされるべき | TED Talkケイト・ラワース

2018.06.04

データで見ると、世界は良くなっているのか、悪くなっているのか?スティーブン・ピンカー

おすすめ 12018.05.21

言語はいかに我々の考えを形作るのかレラ・ボロディツキー

2018.05.02

公的資金による学術研究の成果を自由に見られないのはなぜか?エリカ・ストーン

2018.04.19

子ども達が生涯の読書家になるためにアルヴィン・アービー

2018.04.04

人間の感情の歴史ティファニー・ワット・スミス

2018.01.31

世帯収入ごとの世界の暮らしを覗いてみようアンナ・ロスリング・ロンランド

おすすめ 12018.01.18

職が無くなる未来社会でのお金の稼ぎ方マーティン・フォード

おすすめ 12017.11.16

多様な考え方が持つ革命的な力エリフ・シャファク

2017.10.27

洋楽 おすすめ

RECOMMENDS

洋楽歌詞

ダイナマイトビーティーエス

洋楽最新ヒット2020.08.20

ディス・イズ・ミーグレイテスト・ショーマン・キャスト

洋楽人気動画2018.01.11

グッド・ライフGイージー、ケラーニ

洋楽人気動画2017.01.27

ホワット・ドゥ・ユー・ミーン?ジャスティン・ビーバー

洋楽人気動画2015.08.28

ファイト・ソングレイチェル・プラッテン

洋楽人気動画2015.05.19

ラヴ・ミー・ライク・ユー・ドゥエリー・ゴールディング

洋楽人気動画2015.01.22

アップタウン・ファンクブルーノ・マーズ、マーク・ロンソン

洋楽人気動画2014.11.20

ブレイク・フリーアリアナ・グランデ

洋楽人気動画2014.08.12

ハッピーファレル・ウィリアムス

ポップス2014.01.08

カウンティング・スターズワンリパブリック

ロック2013.05.31

ア・サウザンド・イヤーズクリスティーナ・ペリー

洋楽人気動画2011.10.26

ユー・レイズ・ミー・アップケルティック・ウーマン

洋楽人気動画2008.05.30

ルーズ・ユアセルフエミネム

洋楽人気動画2008.02.21

ドント・ノー・ホワイノラ・ジョーンズ

洋楽人気動画2008.02.15

オンリー・タイムエンヤ

洋楽人気動画2007.10.03

ミス・ア・シングエアロスミス

ロック2007.08.18

タイム・トゥ・セイ・グッバイサラ・ブライトマン

洋楽人気動画2007.06.08

シェイプ・オブ・マイ・ハートスティング

洋楽人気動画2007.03.18

ウィ・アー・ザ・ワールド(U.S.A. フォー・アフリカ)マイケル・ジャクソン

洋楽人気動画2006.05.14

ホテル・カリフォルニアイーグルス

ロック2005.07.06