TED日本語

TED Talks(英語 日本語字幕付き動画)

TED日本語 - デイム・エレン・マッカーサー: 私が世界一周単独航海で学んだ意外なこと

TED Talks

私が世界一周単独航海で学んだ意外なこと

The surprising thing I learned sailing solo around the world

デイム・エレン・マッカーサー

Dame Ellen MacArthur

内容

あなたは、世界一周単独航海で何を学びますか?単独航海者のエレン・マッカーサーが、必要な物だけを揃え地球を周回して帰還すると、世界の機能の仕方について新しい洞察を得ました。世界は連動し、資源には限りがあります。今日の決定が、明日の資源の枯渇を左右するのです。彼女は、世界の経済システムについて、大胆で新しいアイデアを提案します。直線型は終わりにして、全てが周り続ける循環型を目指そう、というのです。

字幕

SCRIPT

Script

When you're a child, anything and everything is possible. The challenge, so often, is hanging on to that as we grow up. And as a four-year-old, I had the opportunity to sail for the first time.

I will never forget the excitement as we closed the coast. I will never forget the feeling of adventure as I climbed on board the boat and stared into her tiny cabin for the first time. But the most amazing feeling was the feeling of freedom, the feeling that I felt when we hoisted her sails. As a four-year-old child, it was the greatest sense of freedom that I could ever imagine. I made my mind up there and then that one day, somehow, I was going to sail around the world.

So I did what I could in my life to get closer to that dream. Age 10, it was saving my school dinner money change. Every single day for eight years, I had mashed potato and baked beans, which cost 4p each, and gravy was free. Every day I would pile up the change on the top of my money box, and when that pile reached a pound, I would drop it in and cross off one of the 100 squares I'd drawn on a piece of paper. Finally, I bought a tiny dinghy. I spent hours sitting on it in the garden dreaming of my goal. I read every book I could on sailing, and then eventually, having been told by my school I wasn't clever enough to be a vet, left school age 17 to begin my apprenticeship in sailing.

So imagine how it felt just four years later to be sitting in a boardroom in front of someone who I knew could make that dream come true. I felt like my life depended on that moment, and incredibly, he said yes. And I could barely contain my excitement as I sat in that first design meeting designing a boat on which I was going to sail solo nonstop around the world. From that first meeting to the finish line of the race, it was everything I'd ever imagined. Just like in my dreams, there were amazing parts and tough parts. We missed an iceberg by 20 feet. Nine times, I climbed to the top of her 90-foot mast. We were blown on our side in the Southern Ocean. But the sunsets, the wildlife, and the remoteness were absolutely breathtaking. After three months at sea, age just 24, I finished in second position. I'd loved it, so much so that within six months I decided to go around the world again, but this time not in a race: to try to be the fastest person ever to sail solo nonstop around the world. Now for this, I needed a different craft: bigger, wider, faster, more powerful. Just to give that boat some scale, I could climb inside her mast all the way to the top. Seventy-five foot long,60 foot wide. I affectionately called her Moby. She was a multihull. When we built her, no one had ever made it solo nonstop around the world in one, though many had tried, but whilst we built her, a Frenchman took a boat 25 percent bigger than her and not only did he make it, but he took the record from 93 days right down to 72. The bar was now much, much higher.

And these boats were exciting to sail. This was a training sail off the French coast. This I know well because I was one of the five crew members on board. Five seconds is all it took from everything being fine to our world going black as the windows were thrust underwater, and that five seconds goes quickly. Just see how far below those guys the sea is. Imagine that alone in the Southern Ocean plunged into icy water, thousands of miles away from land.

It was Christmas Day. I was forging into the Southern Ocean underneath Australia. The conditions were horrendous. I was approaching a part in the ocean which was 2,000 miles away from the nearest town. The nearest land was Antarctica, and the nearest people would be those manning the European Space Station above me. (Laughter) You really are in the middle of nowhere. If you need help, and you're still alive, it takes four days for a ship to get to you and then four days for that ship to get you back to port. No helicopter can reach you out there, and no plane can land. We are forging ahead of a huge storm. Within it, there was 80 knots of wind, which was far too much wind for the boat and I to cope with. The waves were already 40 to 50 feet high, and the spray from the breaking crests was blown horizontally like snow in a blizzard. If we didn't sail fast enough, we'd be engulfed by that storm, and either capsized or smashed to pieces. We were quite literally hanging on for our lives and doing so on a knife edge.

The speed I so desperately needed brought with it danger. We all know what it's like driving a car 20 miles an hour,30,40. It's not too stressful. We can concentrate. We can turn on the radio. Take that 50,60,70, accelerate through to 80,90,100 miles an hour. Now you have white knuckles and you're gripping the steering wheel. Now take that car off road at night and remove the windscreen wipers, the windscreen, the headlights and the brakes. That's what it's like in the Southern Ocean. (Laughter) (Applause) You could imagine it would be quite difficult to sleep in that situation, even as a passenger. But you're not a passenger. You're alone on a boat you can barely stand up in, and you have to make every single decision on board. I was absolutely exhausted, physically and mentally. Eight sail changes in 12 hours. The mainsail weighed three times my body weight, and after each change, I would collapse on the floor soaked with sweat with this freezing Southern Ocean air burning the back of my throat.

But out there, those lowest of the lows are so often contrasted with the highest of the highs. A few days later, we came out of the back of the low. Against all odds, we'd been able to drive ahead of the record within that depression. The sky cleared, the rain stopped, and our heartbeat, the monstrous seas around us were transformed into the most beautiful moonlit mountains.

It's hard to explain, but you enter a different mode when you head out there. Your boat is your entire world, and what you take with you when you leave is all you have. If I said to you all now, "Go off into Vancouver and find everything you will need for your survival for the next three months," that's quite a task. That's food, fuel, clothes, even toilet roll and toothpaste. That's what we do, and when we leave we manage it down to the last drop of diesel and the last packet of food. No experience in my life could have given me a better understanding of the definition of the word "finite." What we have out there is all we have. There is no more.

And never in my life had I ever translated that definition of finite that I'd felt on board to anything outside of sailing until I stepped off the boat at the finish line having broken that record.

(Applause)

Suddenly I connected the dots. Our global economy is no different. It's entirely dependent on finite materials we only have once in the history of humanity. And it was a bit like seeing something you weren't expecting under a stone and having two choices: I either put that stone to one side and learn more about it, or I put that stone back and I carry on with my dream job of sailing around the world.

I chose the first. I put it to one side and I began a new journey of learning, speaking to chief executives, experts, scientists, economists to try to understand just how our global economy works. And my curiosity took me to some extraordinary places.

This photo was taken in the burner of a coal-fired power station. I was fascinated by coal, fundamental to our global energy needs, but also very close to my family. My great-grandfather was a coal miner, and he spent 50 years of his life underground. This is a photo of him, and when you see that photo, you see someone from another era. No one wears trousers with a waistband quite that high in this day and age. (Laughter) But yet, that's me with my great-grandfather, and by the way, they are not his real ears. (Laughter)

We were close. I remember sitting on his knee listening to his mining stories. He talked of the camaraderie underground, and the fact that the miners used to save the crusts of their sandwiches to give to the ponies they worked with underground. It was like it was yesterday. And on my journey of learning, I went to the World Coal Association website, and there in the middle of the homepage, it said, "We have about 118 years of coal left." And I thought to myself, well, that's well outside my lifetime, and a much greater figure than the predictions for oil. But I did the math, and I realized that my great-grandfather had been born exactly 118 years before that year, and I sat on his knee until I was 11 years old, and I realized it's nothing in time, nor in history. And it made me make a decision I never thought I would make: to leave the sport of solo sailing behind me and focus on the greatest challenge I'd ever come across: the future of our global economy.

And I quickly realized it wasn't just about energy. It was also materials. In 2008, I picked up a scientific study looking at how many years we have of valuable materials to extract from the ground: copper,61; tin, zinc,40; silver, 29. These figures couldn't be exact, but we knew those materials were finite. We only have them once. And yet, our speed that we've used these materials has increased rapidly, exponentially. With more people in the world with more stuff, we've effectively seen 100 years of price declines in those basic commodities erased in just 10 years. And this affects all of us. It's brought huge volatility in prices, so much so that in 2011, your average European car manufacturer saw a raw material price increase of 500 million Euros, wiping away half their operating profits through something they have absolutely no control over.

And the more I learned, the more I started to change my own life. I started traveling less, doing less, using less. It felt like actually doing less was what we had to do. But it sat uneasy with me. It didn't feel right. It felt like we were buying ourselves time. We were eking things out a bit longer. Even if everybody changed, it wouldn't solve the problem. It wouldn't fix the system. It was vital in the transition, but what fascinated me was, in the transition to what? What could actually work?

It struck me that the system itself, the framework within which we live, is fundamentally flawed, and I realized ultimately that our operating system, the way our economy functions, the way our economy's been built, is a system in itself. At sea, I had to understand complex systems. I had to take multiple inputs, I had to process them, and I had to understand the system to win. I had to make sense of it. And as I looked at our global economy, I realized it too is that system, but it's a system that effectively can't run in the long term.

And I realized we've been perfecting what's effectively a linear economy for 150 years, where we take a material out of the ground, we make something out of it, and then ultimately that product gets thrown away, and yes, we do recycle some of it, but more an attempt to get out what we can at the end, not by design. It's an economy that fundamentally can't run in the long term, and if we know that we have finite materials, why would we build an economy that would effectively use things up, that would create waste? Life itself has existed for billions of years and has continually adapted to use materials effectively. It's a complex system, but within it, there is no waste. Everything is metabolized. It's not a linear economy at all, but circular.

And I felt like the child in the garden. For the first time on this new journey, I could see exactly where we were headed. If we could build an economy that would use things rather than use them up, we could build a future that really could work in the long term. I was excited. This was something to work towards. We knew exactly where we were headed. We just had to work out how to get there, and it was exactly with this in mind that we created the Ellen MacArthur Foundation in September 2010.

Many schools of thought fed our thinking and pointed to this model: industrial symbiosis, performance economy, sharing economy, biomimicry, and of course, cradle-to-cradle design. Materials would be defined as either technical or biological, waste would be designed out entirely, and we would have a system that could function absolutely in the long term.

So what could this economy look like? Maybe we wouldn't buy light fittings, but we'd pay for the service of light, and the manufacturers would recover the materials and change the light fittings when we had more efficient products. What if packaging was so nontoxic it could dissolve in water and we could ultimately drink it? It would never become waste. What if engines were re-manufacturable, and we could recover the component materials and significantly reduce energy demand. What if we could recover components from circuit boards, reutilize them, and then fundamentally recover the materials within them through a second stage? What if we could collect food waste, human waste? What if we could turn that into fertilizer, heat, energy, ultimately reconnecting nutrients systems and rebuilding natural capital? And cars -- what we want is to move around. We don't need to own the materials within them. Could cars become a service and provide us with mobility in the future? All of this sounds amazing, but these aren't just ideas, they're real today, and these lie at the forefront of the circular economy. What lies before us is to expand them and scale them up.

So how would you shift from linear to circular? Well, the team and I at the foundation thought you might want to work with the top universities in the world, with leading businesses within the world, with the biggest convening platforms in the world, and with governments. We thought you might want to work with the best analysts and ask them the question, "Can the circular economy decouple growth from resource constraints? Is the circular economy able to rebuild natural capital? Could the circular economy replace current chemical fertilizer use?" Yes was the answer to the decoupling, but also yes, we could replace current fertilizer use by a staggering 2.7 times. But what inspired me most about the circular economy was its ability to inspire young people. When young people see the economy through a circular lens, they see brand new opportunities on exactly the same horizon. They can use their creativity and knowledge to rebuild the entire system, and it's there for the taking right now, and the faster we do this, the better.

So could we achieve this in their lifetimes? Is it actually possible? I believe yes. When you look at the lifetime of my great-grandfather, anything's possible. When he was born, there were only 25 cars in the world; they had only just been invented. When he was 14, we flew for the first time in history. Now there are 100,000 charter flights every single day. When he was 45, we built the first computer. Many said it wouldn't catch on, but it did, and just 20 years later we turned it into a microchip of which there will be thousands in this room here today. Ten years before he died, we built the first mobile phone. It wasn't that mobile, to be fair, but now it really is, and as my great-grandfather left this Earth, the Internet arrived. Now we can do anything, but more importantly, now we have a plan.

Thank you.

(Applause)

子どもの頃は何にでもなれます 成長するにつれ 夢にしがみつくのは至難の業になります 4歳の頃 私は初めてヨットに乗ることになりました

海岸に近づいていくときの 興奮は忘れられません ヨットによじ登って 小さなキャビンを初めて覗き込んだ時の 冒険に行くんだという気持ちも 忘れられません でも一番素晴らしかったのは 帆を揚げた時感じた 自由でした 4歳の子供が想像し得る限り目一杯の 素晴らしい自由という感覚だったのです そして 私はいつか どうにかして 世界中を航海すると決めたのでした

その夢に近づくため 自分が出来ることをしました 10歳の時 学校給食のお金を貯めました 8年間毎日ずっと マッシュポテトとベイクドビーンズを食べました 値段は2つとも4ペンスで グレイビーソースは無料でした 毎日私は貯金箱の上に 小銭を重ねました 重ねた小銭が1ポンドになると 貯金箱に入れ 紙に書いた100個の四角のうち 1つを線で消しました そしてようやく 小型のヨットを買いました 庭でヨットの上に何時間も座り 目標の達成を夢見ていました 私はセーリングに関する あらゆる本を読み ついには学校から 「この成績では獣医になれない」と言われ 17歳で学校を辞め セーリングのトレーニングを始めました

想像してみてください その4年後 ある役員会議室で 夢をいよいよ 実現するための面接に臨む気持ちを 自分の人生を左右する瞬間だと 感じていました 驚いたことに 彼の答えは「イエス」 興奮が冷めやらぬまま 私は初めての設計会議に出席しました ノンストップで世界一周単独航海をする 私のヨットの設計会議です 最初の会議からレースのゴールまで すべてが私の想像どおりでした 考えていた通り 素晴らしい部分と辛い部分がありました 6mのところで氷山をかわしたり 9回も 30mのマストの てっぺんまで登りました 南氷洋では横風で転覆しました でも夕焼けや野生生物 どこまでも人のいない世界 これほど心奪われるものはありません 3カ月後 24歳の頃 私は第2位でゴールしました 心の底から惹きつけられて 半年も経たないうちに もう一度世界一周をすると決めました でも今回はレースではなく ノンストップの世界一周単独航海で最速を目指しました これを実現するためには 別のヨットが必要でした もっと大きく 幅ももっと広く もっと速く より強力な船です どんな大きさかと言えば マストの内側を先端まで 登れるようなサイズです 全長23m 横幅18mです 愛情を込めてモービィと命名した 多胴艇です モービィの着工時 多くの人が多胴艇でのノンストップの世界一周単独航海に挑みましたが 誰も成功させた者はいませんでした しかし 建造中に フランス人男性がモービィより25%も大きい船を使い 成功させただけでなく 記録を93日間から 72日間に塗り替えました 目標がぐんと高くなったのです

このタイプの船の 帆走は刺激的です これはフランス沖での航海訓練です 5人の乗員の1人だったので よく覚えています 全てが順調だったのに 5秒後には 世界は真っ暗 窓は水中に沈んでいるのです あっという間の5秒でした 5人の位置から 海面までがどんなに遠いかわかりますね 想像してみてください 岸から3-4,000kmくらい沖の南氷洋で たった一人で投げ出されることを 想像してください

クリスマス当日でした オーストラリアの南の南氷洋を 私はゆっくり進みました 恐ろしい状況でした 私が向かっている海域は 最寄りの町から3000kmは離れた場所 南極大陸が一番近い陸地で 一番近い人は 頭上の宇宙ステーションの 乗組員かもしれない (笑) 名もなき海の真っただ中です 命があって 救助を求めるとしたら 船が来るのに4日かかります そして船が港に戻るのに さらに4日かかるのです ヘリコプターでは辿り着けません 飛行機も着陸できません 巨大な嵐の前をゆっくり進みます 嵐の中では 風速150kmで 船も私も対応できません 波は10-15mの高さで 波の山が崩れておこる水しぶきは ブリザードの雪のように 水平に飛んできました スピードが足りなかったら 嵐に飲み込まれ 転覆するか 粉々にされます 私たちは文字通り 生にしがみつき ぎりぎりのところで踏みとどまっていました

死にもの狂いで出すスピードには 危険が伴いました 時速 30、45、60km で 車を走らせる気分と言えば ストレスはそれほどでもなく 集中できます ラジオだってかけられます 時速 80、100、120km さらに 加速して130、145、160km 白くなった拳でハンドルを握りしめます さてそんな車が夜 道路から外れ ワイパーやフロントガラス ヘッドライトやブレーキがない状態 南氷洋でそういうことをしているのです (笑)(拍手) 想像してみてください そういう状況では乗客であっても 寝るのは難しいのです しかし乗客ではありません ヨットには自分だけで 立つこともままならず あなたはあらゆることを 決めなくてはなりません 精神的にも体力的にも 憔悴しきっています 12時間のうちに8回 帆を交換 主帆は私の体重の3倍の重さです 帆を変えるたびに 私は汗だくになり 床に崩れました 凍えるような南氷洋の空気が 喉の奥をヒリヒリさせます

そこでは こんな極限的な状況と どこまでも素晴らしい状態とが 背中合わせです 数日後 低気圧を抜けました 大きな困難にもかかわらず 記録に勝るペースで その低気圧を抜けられました 空は晴れ 雨は止みました 心臓のように休まず動き続けた 恐ろしい海は 月明かりに照らされて 最も美しい山々に変容しました

説明しにくいのですが 海に出る時モードが変わるのです ヨットが自分の世界のすべてになります 出発時に持ってきたものが 持っているものの全てです 仮に私が今皆さんに 「バンクーバーへ行き 3か月間のサバイバルに必要なものを 揃えなさい」と言ったとしても それはたいそう難しい任務でしょう 食料や燃料や衣服 トイレットペーパーに歯磨き粉など そういうものを揃え 出航すると ディーゼルの最後の一滴や 食べ物の最後の一袋に至るまで やりくりします 他のどんな経験も これより明確に 「限りある」という言葉の意味を 教えてくれはしなかったでしょう そこにある物がすべてなのです それ以上はありません

船上で感じた 「限りある」ということの意味を そのあと初めて考えるようになりました 記録を樹立してゴールして ヨットを降りた後からです

(拍手)

突然 点が繋がりました 世界の経済も同じことです 私たちが人類史上 一度だけ持てる 限りある資源に 完全に依存しています 石の下に隠れた物を思いがけず見つけて 二択をするような状況でした 石を脇に置いて詳しく調べるのか それとも 石を元の場所に戻し 夢の仕事である 世界一周の航海に向かって邁進するのか

私は前者を選びました 石を脇にどかして 新しい学びの旅を始め 経営者や専門家 科学者や経済学者と話し 世界経済がどのように機能するのかを 理解しようとしたのです 好奇心に導かれ 私は特別な場所に行きました

これは石炭燃料の発電所のバーナーで 撮った写真です 世界のエネルギー需要を支える 石炭に私は魅せられました 家系的にも近しいものがあったのです 私の曽祖父は炭坑作業員で 人生の50年間は地下で働きました これは曽祖父の写真です この写真を見れば 時代が違うと お分かりいただけるでしょう ウエストバンドを高くしたズボンを 最近では誰も穿きませんよね (笑) これは曽祖父と一緒の写真です 曽祖父の耳は偽物ですよ (笑)

私たちはとても仲良しで 膝の上に座り 炭鉱の話を聞いたのを覚えています 曽祖父は地下での友情や 地下で一緒に働く小馬にやるために サンドイッチの耳を 炭鉱夫たちが集めていたことを 話してくれました まるで昨日のことのように感じます 私が学びの旅をしていた時 私は世界石炭協会の ホームページを見ました そのホームページの中ごろに 「118年分の石炭が存在」 とありました 私の寿命を超えているので 石油の予想より ずっと明るい数字だと思いました でも計算してみると 曽祖父が生まれたのが その年から数えて 118年前でした 私は11歳まで 曽祖父の膝に座っていましたが 時間や歴史と比べると ごくわずかな時間に過ぎない と気付き そして考えてもみなかったような ある決断をしました 単独航海というスポーツから離れ 私が出会った最大の難題である 世界経済の未来に 注力することにしたのです

すぐに悟ったのが 単にエネルギーの問題だけでなく 資源の問題でもあることでした 2008年 私はある科学研究を見つけました 地下に埋まっている貴重な資源が あと何年分残っているのかを調べたものです 銅は61年 錫と亜鉛は40年 銀は29年です これらの数字が正確でなくとも 物質には「限りがある」のです 使えるのは一度だけです 私たちが資源を使うスピードは 急激に加速しています 世界の人口が増えることで 物が溢れ 100年に渡り緩やかに下がってきた 基本的物質の価格下降は わずか10年で 帳消しになりました これは私たち全員に影響します 2011年には 価格の乱高下を招きました 欧州の普通の自動車会社は 原材料価格が5億ユーロも値上がりするという 全く制御不能な事態により 営業利益の半分を失いました

知れば知るほど 自分の人生が変わり始めたのです 移動も消費も 控えるようになりました 私たちは 行動を控えるべきなのだと 感じたのです でもその考えはしっくりと来ず 腑に落ちませんでした 私たちは ただ時間稼ぎをしているだけだと 感じたのです モノをあと少し 長く使えるように 皆さんが変わったとしても 問題解決にはならないし システムを修正することもできません 消費形態の変化は避けられませんが 私の関心が向いたのは 「どのように変化すればいいのか? 実際何が有効なのか?」ということでした

今の仕組みは 私たちが暮らしていく上で 基本的な欠陥があると感じました 突き詰めていくと 私たちのオペレーティング・システム ― 経済の機能の方法や 経済が構築された方法 それ自体がシステムなのです 海では複雑なシステムを 理解するのは必須でした 私は様々な入力をして それらを処理して システムを理解しなければ 勝てませんでした 意味を理解することが必要でした 世界経済を見ると それもシステムで 長期的に見ると効率が悪いことにも 気付きました

さらに150年かけて 事実上の直線型経済を完成させた ということに気づきました 物質を地中から掘り出して モノを作り そして最後には捨ててしまうのです もちろんリサイクルしている モノもありますが そこには最後まで使い倒すという 意図があるのみで 再利用の為のデザインはなされていません これは 根本的に長期的には 立ち行かない経済なのです 物質に限りがあることを 知っているなら あっと言う間に使い切り ゴミを作り出すような経済を どうして作ったのでしょうか? 生命は何十億年も存在し 効果的に資源を使い続けてきました 複雑なシステムでしたが 廃棄物はありませんでした すべてが代謝されていました 直線型ではなく 循環型の経済でした

あの庭にいた子供の頃の自分のように 感じていました この新しい旅で初めて 目的地を正確に知りました モノを使い切るのではなく 活用する経済を作れたなら 真に長期的に機能する 未来を作れるのです 私はワクワクしました これは取り組み甲斐のある仕事です 目的地が設定できれば 行き方を見出すだけです このことを念頭に置き 2010年9月に エレン・マッカーサー財団を設立しました

様々な学問分野を踏まえて 我々はこんなモデルを示しました 産業共生、利用価値の経済 シェアリングの経済、バイオミミクリー そしてもちろん 完全循環型のデザインです 物質は技術的 あるいは 生物的なものとして定義され 廃棄物も完全に計画に含め 長期的に機能できる 仕組みを作るのです

この経済は どのようなものでしょうか? 照明器具を買わずに 照明サービスに対価を払います 製造業者は製品を回収し もっと効率的な照明器具に 作り変えます 梱包材料が水に溶して飲めるほど 非毒性だったら? 決して廃棄物にはなりません エンジンも再利用できたなら 部品を回収できるので エネルギー需要を激減できるのです 回路基板の部品を回収して再利用し 次の段階で製品中の資源を 根本的に回収できたらどうでしょう? もし食品廃棄物や人糞を集め 肥料や熱やエネルギーに変えたら? 最終的に栄養のシステムを再連結し 自然資本を再構築したら? そして車です ― あちこち出かけたいですが 自分で所有する必要はありません 将来の車としては 私たちに移動手段を提供する サービスがあれば良いのでは? すべて素晴らしいですが これらは単なるアイデアではなく 今日 現実であり 循環型経済の最前線なのです これからの私たちの課題は 循環型経済を広めて規模を拡大することです

どうやって直線型から循環型に 移行するのでしょうか? 当財団では皆さんが協働したいのは 世界の名門大学や 世界のトップ企業や 世界最大級のプラットフォームや 各国政府だと考えました 世界トップのアナリストと協働して 聞いてみたいこと ― 「循環型経済は 成長を資源の制限から切り離せるのか? 循環型経済は 自然資本を再構築できるのか? 循環型経済は 現在の化学肥料の使用を置き換えられるのか? これへの答えは 切り離せますし 驚くべきことに 現在の肥料の2.7倍まで 置き換えられます 循環型経済に 最も刺激を受けたことは 若者に動機付けを与えることです 若者が循環型の眼鏡を通して 経済を見た時 同じ経済を見ても 真新しい機会があることに気付くのです 彼らは全システムを 再構築するために 創造性や知識を使うのです その実現はもうすぐそこです これをするのが 早ければ早いほどいいのです

私たちが生きている間に 達成できるのでしょうか? 実際可能でしょうか? 私はできると信じています 曽祖父の生涯を見ると 何でもできました 曽祖父が生まれた時 世界には25台しか車がありませんでした 車は発明されたばかりだったのです 曽祖父が14歳の時 人類史上初の飛行機が飛びました 今では毎日10万フライトの商用飛行があります 曽祖父が45歳の時 最初のコンピューターが登場しました 多くの人が流行らないと言いましたが 20年後それはマイクロチップとなり 今日この部屋には 何千ものマイクロチップがあります 曽祖父が亡くなる10年前に 最初の携帯電話が登場しました 正確には携帯ではありませんでしたが 現在は本物の携帯電話があります 曽祖父がこの世を去った時 インターネットが登場しました 私たちは何でもできるのです そして もっと重要なことは 私たちには計画があるのです

ありがとうございました

(拍手)

品詞分類

- 主語

- 動詞

- 助動詞

- 準動詞

- 関係詞等

TED 日本語

TED Talks

関連動画

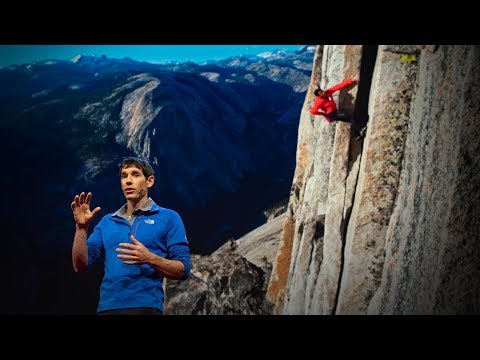

900メートルの絶壁をいかにしてロープなしで登ったのかアレックス・オノルド

2018.10.29

ジェット・スーツができるまでリチャード・ブラウニング

2017.07.17

成層圏からのジャンプ、それをお話ししますアラン・ユースタス

2015.09.28

最後の手つかずの大陸を守れロバート・スワン

2015.01.13

南極点に行って戻る ― 人生で最も厳しい105日間ベン・サンダース

2014.12.02

夢は決してあきらめるなダイアナ・ナイアド

おすすめ 32013.12.23

なぜ家を出なきゃいけないの?ベン・ソーンダーズ

2012.12.14

綱を渡る旅フィリップ・プティ

2012.05.23

世界一危険なクラゲに出会った 私のエクストリームスイムダイアナ・ナイアド

2012.01.24

空駆けるジェットマンイブ・ロッシー

2011.11.15

意識を変えるためのエベレスト水泳ルイス・ピュー

2010.07.30

私が太平洋を漕いで横断する理由ロズ・サベージ

2010.04.28

エベレストにて、奇跡の生還ケン・カムラー

2010.03.18

17分間の息止め世界記録デイビッド・ブレイン

2010.01.19

北極海での水泳ルイス・ピュー

2009.09.09

スカイダイビング世界記録への挑戦スティーブ・トルグリア

2009.09.07

洋楽 おすすめ

RECOMMENDS

洋楽歌詞

ステイザ・キッド・ラロイ、ジャスティン・ビーバー

洋楽最新ヒット2021.08.20

スピーチレス~心の声ナオミ・スコット

洋楽最新ヒット2019.05.23

シェイプ・オブ・ユーエド・シーラン

洋楽人気動画2017.01.30

フェイデッドアラン・ウォーカー

洋楽人気動画2015.12.03

ウェイティング・フォー・ラヴアヴィーチー

洋楽人気動画2015.06.26

シー・ユー・アゲインウィズ・カリファ

洋楽人気動画2015.04.06

シュガーマルーン5

洋楽人気動画2015.01.14

シェイク・イット・オフテイラー・スウィフト

ポップス2014.08.18

オール・アバウト・ザット・ベースメーガン・トレイナー

ポップス2014.06.11

ストーリー・オブ・マイ・ライフワン・ダイレクション

洋楽人気動画2013.11.03

コール・ミー・メイビーカーリー・レイ・ジェプセン

洋楽人気動画2012.03.01

美しき生命コールドプレイ

洋楽人気動画2008.08.04

バッド・デイ~ついてない日の応援歌ダニエル・パウター

洋楽人気動画2008.05.14

サウザンド・マイルズヴァネッサ・カールトン

洋楽人気動画2008.02.19

イッツ・マイ・ライフボン・ジョヴィ

ロック2007.10.11

アイ・ウォント・イット・ザット・ウェイバックストリート・ボーイズ

洋楽人気動画2007.09.14

マイ・ハート・ウィル・ゴー・オンセリーヌ・ディオン

洋楽人気動画2007.07.12

ヒーローマライア・キャリー

洋楽人気動画2007.03.21

オールウェイズ・ラヴ・ユーホイットニー・ヒューストン

洋楽人気動画2007.02.19

オネスティビリー・ジョエル

洋楽人気動画2005.09.16