TED日本語

TED Talks(英語 日本語字幕付き動画)

TED日本語 - ベン・サンダース: 南極点に行って戻る ― 人生で最も厳しい105日間

TED Talks

南極点に行って戻る ― 人生で最も厳しい105日間

To the South Pole and back -- the hardest 105 days of my life

ベン・サンダース

Ben Saunders

内容

今年、探検家のベン・サンダースは、彼の人生で最も野心的な旅に挑戦しました。彼は、ロバート・ファルコン・スコット隊長が1912年で失敗した南極点遠征 ― 南極沿岸から南極点まで3,000キロ、4ヶ月間の往復の旅を達成しようと出発したのでした。このトークは、冒険から帰還してわずか5週間後に初めて行ったものです。サンダースは生々しく、実直に、この不遜とすら言えるミッションを描き出します。彼は、人生で最も困難な決断を迫られたのでした。

字幕

SCRIPT

Script

So in the oasis of intelligentsia that is TED, I stand here before you this evening as an expert in dragging heavy stuff around cold places. I've been leading polar expeditions for most of my adult life, and last month, my teammate Tarka L'Herpiniere and I finished the most ambitious expedition I've ever attempted. In fact, it feels like I've been transported straight here from four months in the middle of nowhere, mostly grunting and swearing, straight to the TED stage. So you can imagine that's a transition that hasn't been entirely seamless. One of the interesting side effects seems to be that my short-term memory is entirely shot. So I've had to write some notes to avoid too much grunting and swearing in the next 17 minutes. This is the first talk I've given about this expedition, and while we weren't sequencing genomes or building space telescopes, this is a story about giving everything we had to achieve something that hadn't been done before. So I hope in that you might find some food for thought.

It was a journey, an expedition in Antarctica, the coldest, windiest, driest and highest altitude continent on Earth. It's a fascinating place. It's a huge place. It's twice the size of Australia, a continent that is the same size as China and India put together.

As an aside, I have experienced an interesting phenomenon in the last few days, something that I expect Chris Hadfield may get at TED in a few years' time, conversations that go something like this: "Oh, Antarctica. Awesome. My husband and I did Antarctica with Lindblad for our anniversary." Or, "Oh cool, did you go there for the marathon?" (Laughter)

Our journey was, in fact,69 marathons back to back in 105 days, an 1, 800-mile round trip on foot from the coast of Antarctica to the South Pole and back again. In the process, we broke the record for the longest human-powered polar journey in history by more than 400 miles. (Applause) For those of you from the Bay Area, it was the same as walking from here to San Francisco, then turning around and walking back again. So as camping trips go, it was a long one, and one I've seen summarized most succinctly here on the hallowed pages of Business Insider Malaysia. [ "Two Explorers Just Completed A Polar Expedition That Killed Everyone The Last Time It Was Attempted" ]

Chris Hadfield talked so eloquently about fear and about the odds of success, and indeed the odds of survival. Of the nine people in history that had attempted this journey before us, none had made it to the pole and back, and five had died in the process.

This is Captain Robert Falcon Scott. He led the last team to attempt this expedition. Scott and his rival Sir Ernest Shackleton, over the space of a decade, both led expeditions battling to become the first to reach the South Pole, to chart and map the interior of Antarctica, a place we knew less about, at the time, than the surface of the moon, because we could see the moon through telescopes. Antarctica was, for the most part, a century ago, uncharted.

Some of you may know the story. Scott's last expedition, the Terra Nova Expedition in 1910, started as a giant siege-style approach. He had a big team using ponies, using dogs, using petrol-driven tractors, dropping multiple, pre-positioned depots of food and fuel through which Scott's final team of five would travel to the Pole, where they would turn around and ski back to the coast again on foot. Scott and his final team of five arrived at the South Pole in January 1912 to find they had been beaten to it by a Norwegian team led by Roald Amundsen, who rode on dogsled. Scott's team ended up on foot. And for more than a century this journey has remained unfinished. Scott's team of five died on the return journey. And for the last decade, I've been asking myself why that is. How come this has remained the high-water mark? Scott's team covered 1,600 miles on foot. No one's come close to that ever since. So this is the high-water mark of human endurance, human endeavor, human athletic achievement in arguably the harshest climate on Earth. It was as if the marathon record has remained unbroken since 1912. And of course some strange and predictable combination of curiosity, stubbornness, and probably hubris led me to thinking I might be the man to try to finish the job.

Unlike Scott's expedition, there were just two of us, and we set off from the coast of Antarctica in October last year, dragging everything ourselves, a process Scott called "man-hauling." When I say it was like walking from here to San Francisco and back, I actually mean it was like dragging something that weighs a shade more than the heaviest ever NFL player. Our sledges weighed 200 kilos, or 440 pounds each at the start, the same weights that the weakest of Scott's ponies pulled. Early on, we averaged 0.5 miles per hour. Perhaps the reason no one had attempted this journey until now, in more than a century, was that no one had been quite stupid enough to try. And while I can't claim we were exploring in the genuine Edwardian sense of the word -- we weren't naming any mountains or mapping any uncharted valleys -- I think we were stepping into uncharted territory in a human sense. Certainly, if in the future we learn there is an area of the human brain that lights up when one curses oneself, I won't be at all surprised.

You've heard that the average American spends 90 percent of their time indoors. We didn't go indoors for nearly four months. We didn't see a sunset either. It was 24-hour daylight. Living conditions were quite spartan. I changed my underwear three times in 105 days and Tarka and I shared 30 square feet on the canvas. Though we did have some technology that Scott could never have imagined. And we blogged live every evening from the tent via a laptop and a custom-made satellite transmitter, all of which were solar-powered: we had a flexible photovoltaic panel over the tent. And the writing was important to me. As a kid, I was inspired by the literature of adventure and exploration, and I think we've all seen here this week the importance and the power of storytelling.

So we had some 21st-century gear, but the reality is that the challenges that Scott faced were the same that we faced: those of the weather and of what Scott called glide, the amount of friction between the sledges and the snow. The lowest wind chill we experienced was in the -70s, and we had zero visibility, what's called white-out, for much of our journey. We traveled up and down one of the largest and most dangerous glaciers in the world, the Beardmore glacier. It's 110 miles long; most of its surface is what's called blue ice. You can see it's a beautiful, shimmering steel-hard blue surface covered with thousands and thousands of crevasses, these deep cracks in the glacial ice up to 200 feet deep. Planes can't land here, so we were at the most risk, technically, when we had the slimmest chance of being rescued.

We got to the South Pole after 61 days on foot, with one day off for bad weather, and I'm sad to say, it was something of an anticlimax. There's a permanent American base, the Amundsen-Scott South Pole Station at the South Pole. They have an airstrip, they have a canteen, they have hot showers, they have a post office, a tourist shop, a basketball court that doubles as a movie theater. So it's a bit different these days, and there are also acres of junk. I think it's a marvelous thing that humans can exist 365 days of the year with hamburgers and hot showers and movie theaters, but it does seem to produce a lot of empty cardboard boxes. You can see on the left of this photograph, several square acres of junk waiting to be flown out from the South Pole. But there is also a pole at the South Pole, and we got there on foot, unassisted, unsupported, by the hardest route,900 miles in record time, dragging more weight than anyone in history. And if we'd stopped there and flown home, which would have been the eminently sensible thing to do, then my talk would end here and it would end something like this.

If you have the right team around you, the right tools, the right technology, and if you have enough self-belief and enough determination, then anything is possible.

But then we turned around, and this is where things get interesting. High on the Antarctic plateau, over 10,000 feet, it's very windy, very cold, very dry, we were exhausted. We'd covered 35 marathons, we were only halfway, and we had a safety net, of course, of ski planes and satellite phones and live, 24-hour tracking beacons that didn't exist for Scott, but in hindsight, rather than making our lives easier, the safety net actually allowed us to cut things very fine indeed, to sail very close to our absolute limits as human beings. And it is an exquisite form of torture to exhaust yourself to the point of starvation day after day while dragging a sledge full of food.

For years, I'd been writing glib lines in sponsorship proposals about pushing the limits of human endurance, but in reality, that was a very frightening place to be indeed. We had, before we'd got to the Pole,two weeks of almost permanent headwind, which slowed us down. As a result, we'd had several days of eating half rations. We had a finite amount of food in the sledges to make this journey, so we were trying to string that out by reducing our intake to half the calories we should have been eating. As a result, we both became increasingly hypoglycemic -- we had low blood sugar levels day after day -- and increasingly susceptible to the extreme cold. Tarka took this photo of me one evening after I'd nearly passed out with hypothermia. We both had repeated bouts of hypothermia, something I hadn't experienced before, and it was very humbling indeed. As much as you might like to think, as I do, that you're the kind of person who doesn't quit, that you'll go down swinging, hypothermia doesn't leave you much choice. You become utterly incapacitated. It's like being a drunk toddler. You become pathetic. I remember just wanting to lie down and quit. It was a peculiar, peculiar feeling, and a real surprise to me to be debilitated to that degree.

And then we ran out of food completely,46 miles short of the first of the depots that we'd laid on our outward journey. We'd laid 10 depots of food, literally burying food and fuel, for our return journey -- the fuel was for a cooker so you could melt snow to get water -- and I was forced to make the decision to call for a resupply flight, a ski plane carrying eight days of food to tide us over that gap. They took 12 hours to reach us from the other side of Antarctica.

Calling for that plane was one of the toughest decisions of my life. And I sound like a bit of a fraud standing here now with a sort of belly. I've put on 30 pounds in the last three weeks. Being that hungry has left an interesting mental scar, which is that I've been hoovering up every hotel buffet that I can find. (Laughter) But we were genuinely quite hungry, and in quite a bad way. I don't regret calling for that plane for a second, because I'm still standing here alive, with all digits intact, telling this story. But getting external assistance like that was never part of the plan, and it's something my ego is still struggling with. This was the biggest dream I've ever had, and it was so nearly perfect.

On the way back down to the coast, our crampons -- they're the spikes on our boots that we have for traveling over this blue ice on the glacier -- broke on the top of the Beardmore. We still had 100 miles to go downhill on very slippery rock-hard blue ice. They needed repairing almost every hour. To give you an idea of scale, this is looking down towards the mouth of the Beardmore Glacier. You could fit the entirety of Manhattan in the gap on the horizon. That's 20 miles between Mount Hope and Mount Kiffin. I've never felt as small as I did in Antarctica. When we got down to the mouth of the glacier, we found fresh snow had obscured the dozens of deep crevasses. One of Shackleton's men described crossing this sort of terrain as like walking over the glass roof of a railway station. We fell through more times than I can remember, usually just putting a ski or a boot through the snow. Occasionally we went in all the way up to our armpits, but thankfully never deeper than that.

And less than five weeks ago, after 105 days, we crossed this oddly inauspicious finish line, the coast of Ross Island on the New Zealand side of Antarctica. You can see the ice in the foreground and the sort of rubbly rock behind that. Behind us lay an unbroken ski trail of nearly 1,800 miles. We'd made the longest ever polar journey on foot, something I'd been dreaming of doing for a decade.

And looking back, I still stand by all the things I've been saying for years about the importance of goals and determination and self-belief, but I'll also admit that I hadn't given much thought to what happens when you reach the all-consuming goal that you've dedicated most of your adult life to, and the reality is that I'm still figuring that bit out. As I said, there are very few superficial signs that I've been away. I've put on 30 pounds. I've got some very faint, probably covered in makeup now, frostbite scars. I've got one on my nose,one on each cheek, from where the goggles are, but inside I am a very different person indeed. If I'm honest, Antarctica challenged me and humbled me so deeply that I'm not sure I'll ever be able to put it into words. I'm still struggling to piece together my thoughts. That I'm standing here telling this story is proof that we all can accomplish great things, through ambition, through passion, through sheer stubbornness, by refusing to quit, that if you dream something hard enough, as Sting said, it does indeed come to pass. But I'm also standing here saying, you know what, that cliche about the journey being more important than the destination? There's something in that. The closer I got to my finish line, that rubbly, rocky coast of Ross Island, the more I started to realize that the biggest lesson that this very long, very hard walk might be teaching me is that happiness is not a finish line, that for us humans, the perfection that so many of us seem to dream of might not ever be truly attainable, and that if we can't feel content here, today, now, on our journeys amidst the mess and the striving that we all inhabit, the open loops, the half-finished to-do lists, the could-do-better-next-times, then we might never feel it.

A lot of people have asked me, what next? Right now, I am very happy just recovering and in front of hotel buffets. But as Bob Hope put it, I feel very humble, but I think I have the strength of character to fight it. (Laughter)

Thank you.

(Applause)

インテリのオアシスである TEDのみなさんを前にして 寒い場所で重いものを引っ張るエキスパートの私が お話をさせていただきます 成人してからのほとんどは極地での探検者 として過ごしてきました 先月 チームメイトである タルカ・ラピニエール と 人生でもっとも野心的な探検を終えてきました 実のところ 不満と文句ばかりで何もない場所から 4ヶ月間の探検を終えてすぐ まっすぐここへ運ばれてきたような感覚でいます そのため まだ頭の切り替えがうまくいっていません 探検の不思議な副作用により 私の短期記憶は完全にダメになったようなのです だから 不満と文句の17分を回避するために メモを用意しました この探検の話をするのは初めてです これは 遺伝子の解読や宇宙望遠鏡の建設ではなく 過去 誰も成し遂げられなかったことをなすために 我々の全てをささげた話です 少しでもみなさんの考えるヒントになればと思います

地球上で もっとも寒く 過酷で 乾燥し 標高の高い大陸である 南極大陸での探検の旅でした 南極は魅力的で 広大です オーストラリアの2倍の大きさで 中国とインドを足したほどの大きさです

話がそれますが この数日 興味深い現象を経験しました 数年後 TEDでクリス・ハドフィールドが 次のようなことを話すことになるのではないかと 「あぁ 南極 最高だわよ 夫と私の記念にリンドブラードと南極へ行ったわ」 とか 「イイね マラソンで南極に行ったんですって?」 (笑)

我々の旅はマラソンの距離で69回分 南極の海岸から南極点まで歩き そしてまた戻ってくる 105日 約3,000キロの旅です 我々はこの過程で 極地での人力移動距離の最長記録を 約640キロ更新しました (拍手) 西海岸沿いの方のためにご説明すると ここからサンフランシスコまで歩いてから また歩いて戻ってくるという道のりです キャンプ旅行としては 相当に長い道のりでした マレーシアのビジネスインサイダー紙に よくまとめられた記事が載っているので 紹介しましょう [過去 幾多の探検家が亡くなった極地での冒険を 2名は成し遂げた]

クリス・ハドフィールドは 探検での恐怖、成功、そして生存の可能性について雄弁に語っています 我々以前に 9名がチャレンジし 1人として極点を往復できず 途中で5名が亡くなっています

ロバート・ファルコン・スコット隊長です この冒険を試みた最後の部隊を率いました 彼とライバルのアーネスト・シャクルトン卿の探検隊は 南極点に最初に到着し 南極大陸の測量を行うために 10年にわたって競い合いました その当時 南極大陸は 天体望遠鏡で観察できる月面よりも 知られていなかったのです 南極大陸の大部分は 100年前には測量されていませんでした

ご存知の方もいらっしゃるでしょう スコット隊長の最後の探検 1910年のテラ・ノヴァ号の探検は 壮大な極地法で始まりました ポニーや犬 石油で動くトラクター等を使って 南極点に向かうスコット隊の 最後の5名が通る区間に たくさんの食料と燃料を事前に配備して その後 5名は南極点で折り返し 徒歩でそりを引いて戻る計画でした スコットと最後の5名のチームは 1912年の1月に南極点に到着しましたが 犬ぞりを使った ノルウェーのロアルド・アムンゼン隊に 先を越されたことを知りました スコット隊は最後は徒歩でした それから100年以上の間 人力での南極点到達は未達のままでした 5名のスコット隊は復路で全滅したからです 過去10年間の間 私はその理由を考え続けました なぜ スコット隊の記録が その後も塗り替えられないのか? スコット隊は2,500キロを徒歩で歩きました それ以来 誰もその記録に近づけていません だから それが地球上 最も過酷な気候での 人類の忍耐 努力 肉体的成果の最高到達点なのです これはマラソンの記録が 1912年以来破られていないようなものです 好奇心 頑固さ または尊大さなど もちろん 多少突飛ですが ご想像の通りの要素が一緒になり ひょっとして自分がこの偉業を成し遂げる男になれる かもしれないと考えさせました

スコットの探検と異なり 我々は二人だけです そして昨年の10月に持ち物を全部引きずって 南極の海岸を出発しました スコットが 「人力輸送」と呼んだ方法です ここからサンフランシスコまで 歩いて往復するといいましたが 実際にはNFL史上最も重い選手よりも 少し重いくらいの荷物を引きずっていました 我々のそりはスタート時点で 200キロまたは440ポンドあり スコット隊の最も弱いポニーが 引っ張った重さと同じです 最初は 我々は時速800mでした 多分 100年以上もの間 この旅が行われなかった理由は これに挑戦するほど馬鹿な人が いなかったからでしょう まさしくエドワード朝時代の方法であったと 主張することは出来ませんが ― どの山の名前を名づけることもなく 未測量の谷も地図に記しませんでした 人類が未だ測量したことのない土地に 足を踏み入れたと思います 人類の脳に自身を呪う時に点灯する部分を 我々が将来知ることがあるとしても きっと驚きはしないでしょう

一般的なアメリカ人は90%の時間を屋内で過ごします 我々はほぼ4ヶ月屋内に入らなかったのです 日没も見ませんでした 24時間 昼間です 生活環境はとても苛酷です 105日間 下着は3回しか替えませんでした タルカと私は2.7㎡のテントを共有しました スコットが夢想だにしなかった いくつかのテクノロジーもありました 毎晩テントから 太陽光発電の 特注の衛星通信機器とパソコンで ブログを書いていました テントの上には折り曲げ可能な 太陽電池パネルがありました 私にとって書くことはとても重要でした 子供の頃 冒険や探検文学に影響されましたが 皆さんも今週ここで 物語を話すことの大切さと力を知ったでしょう

21世紀の装置を使っていましたが 我々が実際に体験した現実は スコットが直面した困難と同じものでした 天候であり スコットがグライドと呼んだ そりと雪の間の大量の摩擦抵抗でした 経験した暴風雪の最低温度はマイナス70度 旅のほとんどは ホワイトアウトと呼ばれる 視界ゼロの状態でした 世界で最も大きく危険な氷河の一つである ベアドモア氷河を上り下りしました 全長180キロで 表面のほとんどは ブルーアイスと呼ばれるものです きれいでキラキラ光る 鉄のように固い青い表面が 最深60メートルにもなる 氷河の深い亀裂 何千ものクレバスが覆っています 飛行機は着陸できません そのため 実質的に救助される可能性が最も低く 最大の危険にさらされます

我々は悪天候のため 1日遅れの 61日目に徒歩で南極点に到着しましたが 残念なことに ここは期待はずれでした 南極点には アメリカの常設基地である アムンゼン・スコット基地があります 滑走路があり 食堂があり 温水シャワーもあります 郵便局や土産物屋 映画館としても使われている バスケットボールコートもあります 最近はちょっと違うのです そして 多くのごみが捨てられています 人類が年間365日 ハンバーガーと温水シャワーと映画館のある 生活が出来るのは素晴らしいと思いますが 同時に多くの空の段ボール箱が 生み出されているように見えます この写真の左側には 南極から飛行機での搬出を待っている 何エーカーものごみの山が見えます しかし 南極点には 我々が 誰の力も借りずに 最も険しいルートを助けもなく 1,500キロを 史上最速で 歴史上の誰よりも重い荷物を引きずり 踏破したという記念碑があります もし我々が中断して飛行機で家に帰ったら もちろんそれは極めて常識的な判断ですが 私の話はここで終わり 結末はこういったものになるでしょう

正しいチームが周りにいて 正しい道具と テクノロジーがあり 十分な自信と決意があるのなら 不可能はありません

しかしもし引き返したら 物語は面白くなります 3000メートルを超える南極の高地は 風が強く とても寒い場所で 我々は疲弊していました 35回分のマラソンをし まだ道半ばです スコットの時代にはなかった 雪上飛行機や携帯電話 24時間の追跡無線装置などの セーフティネットも当然ありました しかし 後から分かることですが 安全装置は 人生を簡単にすることよりも 人類の限界に限りなく 近いところに踏み出すための 微妙な判断を可能にするのです 人類の限界への旅は 激しい拷問で 毎日食糧一杯のそりを曳いていながら 毎日飢えにより疲弊していきます

何年もの間 支援者への提案の中で 人類の忍耐の限界への挑戦などと 軽薄な文章を書いてきましたが 実際には とても怖い環境でした 南極点に到着する前は 二週間のほとんど止むことのない逆風が 我々の歩みを遅らせました その結果 何日かの間 半分の量しか食べられませんでした 旅のためにそりに積まれた食糧は 限られていたので 摂取カロリーを必要量の半分にすることで 食糧を長持ちさせようとしたのです その結果 二人は徐々に低血糖になり ― 血糖値が日に日に下がっていき ― 極寒に敏感になっていきました タルカはある日 低体温で気絶しそうな私の写真をとりました 二人とも何度も低体温症の発作に襲われました かつて経験したこともなく とても屈辱的です 私がそうであったように 自分はくじけない人間だと思うほど そのダメージは大きくなります 低体温症は選択肢を与えてくれません 完全に無力になります よっぱらった幼児のようです 惨めな姿になります ただ寝て止めたいと願ったのを覚えています とても とても奇妙な感覚です そこまで衰弱するのは本当に驚きでした

ついに食糧は底をつきました 我々が旅を始めた 最初の補給所から46マイル手前です 我々は復路のために文字通り食糧と燃料を埋めた 10ヶ所の食糧補給所を用意していました 燃料は雪を溶かし水を作る 調理器具用です 私は補給機を呼ぶかの選択を迫られました 雪上飛行機はこの区間を乗り越える 8日分の食糧を運んでくれます 南極の反対側から12時間かかりました

飛行機を呼ぶのは私の人生で 最もつらい決断の一つでした だからこんな腹をしてここに立っているのは 詐欺のように聞こえます この3週間で私は15キロ太りました あまりの空腹は面白い心の傷を残しました ホテルのビュッフェを見つけるたびに 食べあさってしまうのです (笑) 実際 我々は極めて悪い意味で 本当に空腹でした ここに生きて立って 無傷で この話ができるのですから 補給機を呼んだことに微塵も後悔はありません しかし 外部の助けを呼ぶことは 計画に全くなかったので 自分の心の中はいまだに葛藤しています この旅は 私の最大の夢であり ほとんど完璧でした

海岸線に戻る道のり ベアドモア氷河の頂上で 我々のクランポン ― 氷河のブルーアイスの上を旅するための ブーツのスパイクが壊れました 滑りやすい岩のように固い ブルーアイスの下り坂が 160キロも残っていました ほぼ毎時 クランポンを直す必要がありました 規模のイメージをお伝えするため ベアドモア氷河の入り口を見下ろしています 地平線上のくぼみにマンハッタンが すっぽり入ります マウント・ホープとマウント・キフィンの間は 約32キロです 私は南極にいたときほど 自分が小さく感じたことがありません 氷河の入り口に下りていくと 新雪が何十もの深いクレバスを 覆っていることがわかります シャクルトン卿の部下達は このような地域を歩いてわたることを 列車の駅のガラス窓の上を 歩くようだと表現しました たいていはスキーやブーツが 雪を突き抜ける程度ですが 数え切れないくらいクレバスに落ちました あるときは 脇ぐらいまで落ちましたが 幸いにもそれ以上は落ちませんでした

そしてたった5週間前 105日間の後 南極のニュージーランド側のロス島の海岸で 多難の末のゴールを迎えました 手前に氷が見えますが 後ろには荒々しい岩が見えます 後ろには途切れることのない 1,800マイルのスキー跡があります 私が10年もの間 あこがれていた 至上最も長い徒歩での極地旅行を 我々は成し遂げたのです

そして 今振り返ってみても 私はまだ同じ考えを持っています 私は何年もの間 ゴールの重要性や 意志の固さや 自信について語ってきましたが 人生のほとんどをささげてきた ゴール地点に到達したときに 何が起こるかについて あまり考えていなかったこと また現実にはまだそれを探し続けていると 認めざるをえません お話したように 私が旅をした 目に見える証拠はほとんどありません 15キロも太ったからです 今はメイクで隠れてしまっていますが 何箇所かかすかな凍傷の跡はあります ゴーグルをしていた 鼻と両頬のあたりです しかし 私の内面は全く違った人間です 正直にお話しすれば 南極は私に挑みかけ 将来も言葉に表せるか分からないほど 私のプライドをズタズタにしました 私はまだ自分の考えを まとめることに苦労しています ここに私が立ってお話できることは 我々の全てが 野心や情熱 撤退を拒む 純粋な頑なさにより 偉大な何かを成し遂げられるということです それはスティングが言ったように 「夢を強く願うなら それは叶う」 というようなものです しかし ご存知かもしれませんが 私はここで 「旅程の方が目的地より重要だ」 という言葉をお伝えしたいと思います これには大切なことが含まれているからです 私が あのロス島の荒々しい岩の海岸の ゴールに近づくにつれ とても大きなことを感じ始めました とても長く 過酷な徒歩が 私に教えてくれたことは 人間にとって ゴールに着くことが幸福ではないということ 多くの人々が夢見る完璧さは 決して手に入らないのかもしれないということ 混乱や努力 終わりのない世界 や やりかけの仕事たち 次回はもっと上手にできるという 人生の旅の中で 今 ここで 満たされないのだとしたら 決して幸福は 感じられないのではないかということ

多くの人が私に 「次は何に挑戦するの」とたずねます 今の私は 回復するだけでも ホテルのビュッフェに入るだけでもとても幸せです しかしボブ・ホープは言いました 「とても光栄ではありますが まだここに満足しない頑固な性格です」と (笑)

ありがとう

(拍手)

品詞分類

- 主語

- 動詞

- 助動詞

- 準動詞

- 関係詞等

TED 日本語

TED Talks

関連動画

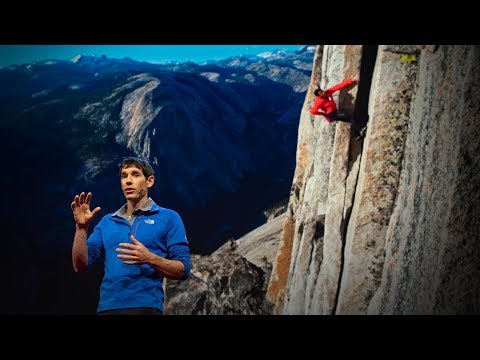

900メートルの絶壁をいかにしてロープなしで登ったのかアレックス・オノルド

2018.10.29

ジェット・スーツができるまでリチャード・ブラウニング

2017.07.17

成層圏からのジャンプ、それをお話ししますアラン・ユースタス

2015.09.28

私が世界一周単独航海で学んだ意外なことデイム・エレン・マッカーサー

おすすめ 22015.06.29

最後の手つかずの大陸を守れロバート・スワン

2015.01.13

夢は決してあきらめるなダイアナ・ナイアド

おすすめ 32013.12.23

なぜ家を出なきゃいけないの?ベン・ソーンダーズ

2012.12.14

綱を渡る旅フィリップ・プティ

2012.05.23

世界一危険なクラゲに出会った 私のエクストリームスイムダイアナ・ナイアド

2012.01.24

空駆けるジェットマンイブ・ロッシー

2011.11.15

意識を変えるためのエベレスト水泳ルイス・ピュー

2010.07.30

私が太平洋を漕いで横断する理由ロズ・サベージ

2010.04.28

エベレストにて、奇跡の生還ケン・カムラー

2010.03.18

17分間の息止め世界記録デイビッド・ブレイン

2010.01.19

北極海での水泳ルイス・ピュー

2009.09.09

スカイダイビング世界記録への挑戦スティーブ・トルグリア

2009.09.07

洋楽 おすすめ

RECOMMENDS

洋楽歌詞

ステイザ・キッド・ラロイ、ジャスティン・ビーバー

洋楽最新ヒット2021.08.20

スピーチレス~心の声ナオミ・スコット

洋楽最新ヒット2019.05.23

シェイプ・オブ・ユーエド・シーラン

洋楽人気動画2017.01.30

フェイデッドアラン・ウォーカー

洋楽人気動画2015.12.03

ウェイティング・フォー・ラヴアヴィーチー

洋楽人気動画2015.06.26

シー・ユー・アゲインウィズ・カリファ

洋楽人気動画2015.04.06

シュガーマルーン5

洋楽人気動画2015.01.14

シェイク・イット・オフテイラー・スウィフト

ポップス2014.08.18

オール・アバウト・ザット・ベースメーガン・トレイナー

ポップス2014.06.11

ストーリー・オブ・マイ・ライフワン・ダイレクション

洋楽人気動画2013.11.03

コール・ミー・メイビーカーリー・レイ・ジェプセン

洋楽人気動画2012.03.01

美しき生命コールドプレイ

洋楽人気動画2008.08.04

バッド・デイ~ついてない日の応援歌ダニエル・パウター

洋楽人気動画2008.05.14

サウザンド・マイルズヴァネッサ・カールトン

洋楽人気動画2008.02.19

イッツ・マイ・ライフボン・ジョヴィ

ロック2007.10.11

アイ・ウォント・イット・ザット・ウェイバックストリート・ボーイズ

洋楽人気動画2007.09.14

マイ・ハート・ウィル・ゴー・オンセリーヌ・ディオン

洋楽人気動画2007.07.12

ヒーローマライア・キャリー

洋楽人気動画2007.03.21

オールウェイズ・ラヴ・ユーホイットニー・ヒューストン

洋楽人気動画2007.02.19

オネスティビリー・ジョエル

洋楽人気動画2005.09.16