TED日本語

TED Talks(英語 日本語字幕付き動画)

TED日本語 - ベン・ソーンダーズ: なぜ家を出なきゃいけないの?

TED Talks

なぜ家を出なきゃいけないの?

Why bother leaving the house?

ベン・ソーンダーズ

Ben Saunders

内容

探検家ベン・ソーンダーズはあなたにも外の世界を見てほしいのです!心地よい幸せばかりではありませんが、人生を底から満足させる冒険があるからです。ソーンダーズの次の挑戦は?史上初 南極大陸の端から南極点までを徒歩で往復することです。

字幕

SCRIPT

Script

I essentially drag sledges for a living, so it doesn't take an awful lot to flummox me intellectually, but I'm going to read this question from an interview earlier this year: "Philosophically, does the constant supply of information steal our ability to imagine or replace our dreams of achieving? After all, if it is being done somewhere by someone, and we can participate virtually, then why bother leaving the house?"

I'm usually introduced as a polar explorer. I'm not sure that's the most progressive or 21st-century of job titles, but I've spent more than two percent now of my entire life living in a tent inside the Arctic Circle, so I get out of the house a fair bit. And in my nature, I guess, I am a doer of things more than I am a spectator or a contemplator of things, and it's that dichotomy, the gulf between ideas and action that I'm going to try and explore briefly.

The pithiest answer to the question "why?" that's been dogging me for the last 12 years was credited certainly to this chap, the rakish-looking gentleman standing at the back, second from the left, George Lee Mallory. Many of you will know his name. In 1924 he was last seen disappearing into the clouds near the summit of Mt. Everest. He may or may not have been the first person to climb Everest, more than 30 years before Edmund Hillary. No one knows if he got to the top. It's still a mystery. But he was credited with coining the phrase, "Because it's there." Now I'm not actually sure that he did say that. There's very little evidence to suggest it, but what he did say is actually far nicer, and again, I've printed this. I'm going to read it out.

"The first question which you will ask and which I must try to answer is this: What is the use of climbing Mt. Everest? And my answer must at once be, it is no use. There is not the slightest prospect of any gain whatsoever. Oh, we may learn a little about the behavior of the human body at high altitudes, and possibly medical men may turn our observation to some account for the purposes of aviation, but otherwise nothing will come of it. We shall not bring back a single bit of gold or silver, and not a gem, nor any coal or iron. We shall not find a single foot of earth that can be planted with crops to raise food. So it is no use. If you can not understand that there is something in man which responds to the challenge of this mountain and goes out to meet it, that the struggle is the struggle of life itself upward and forever upward, then you won't see why we go. What we get from this adventure is just sheer joy, and joy, after all, is the end of life. We don't live to eat and make money. We eat and make money to be able to enjoy life. That is what life means, and that is what life is for."

Mallory's argument that leaving the house, embarking on these grand adventures is joyful and fun, however, doesn't tally that neatly with my own experience. The furthest I've ever got away from my front door was in the spring of 2004. I still don't know exactly what came over me, but my plan was to make a solo and unsupported crossing of the Arctic Ocean. I planned essentially to walk from the north coast of Russia to the North Pole, and then to carry on to the north coast of Canada. No one had ever done this. I was 26 at the time. A lot of experts were saying it was impossible, and my mum certainly wasn't very keen on the idea. (Laughter)

The journey from a small weather station on the north coast of Siberia up to my final starting point, the edge of the pack ice, the coast of the Arctic Ocean, took about five hours, and if anyone watched fearless Felix Baumgartner going up, rather than just coming down, you'll appreciate the sense of apprehension, as I sat in a helicopter thundering north, and the sense, I think if anything, of impending doom. I sat there wondering what on Earth I had gotten myself into. There was a bit of fun, a bit of joy. I was 26. I remember sitting there looking down at my sledge. I had my skis ready to go, I had a satellite phone, a pump-action shotgun in case I was attacked by a polar bear. I remember looking out of the window and seeing the second helicopter. We were both thundering through this incredible Siberian dawn, and part of me felt a bit like a cross between Jason Bourne and Wilfred Thesiger. Part of me felt quite proud of myself, but mostly I was just utterly terrified.

And that journey lasted 10 weeks,72 days. I didn't see anyone else. We took this photo next to the helicopter. Beyond that, I didn't see anyone for 10 weeks. The North Pole is slap bang in the middle of the sea, so I'm traveling over the frozen surface of the Arctic Ocean. NASA described conditions that year as the worst since records began. I was dragging 180 kilos of food and fuel and supplies, about 400 pounds. The average temperature for the 10 weeks was minus 35. Minus 50 was the coldest. So again, there wasn't an awful lot of joy or fun to be had.

One of the magical things about this journey, however, is that because I'm walking over the sea, over this floating, drifting, shifting crust of ice that's floating on top of the Arctic Ocean is it's an environment that's in a constant state of flux. The ice is always moving, breaking up, drifting around, refreezing, so the scenery that I saw for nearly 3 months was unique to me. No one else will ever, could ever, possibly see the views, the vistas, that I saw for 10 weeks. And that, I guess, is probably the finest argument for leaving the house. I can try to tell you what it was like, but you'll never know what it was like, and the more I try to explain that I felt lonely, I was the only human being in 5.4 million square-miles, it was cold, nearly minus 75 with windchill on a bad day, the more words fall short, and I'm unable to do it justice. And it seems to me, therefore, that the doing, you know, to try to experience, to engage, to endeavor, rather than to watch and to wonder, that's where the real meat of life is to be found, the juice that we can suck out of our hours and days. And I would add a cautionary note here, however. In my experience, there is something addictive about tasting life at the very edge of what's humanly possible. Now I don't just mean in the field of daft macho Edwardian style derring-do, but also in the fields of pancreatic cancer, there is something addictive about this, and in my case, I think polar expeditions are perhaps not that far removed from having a crack habit. I can't explain quite how good it is until you've tried it, but it has the capacity to burn up all the money I can get my hands on, to ruin every relationship I've ever had, so be careful what you wish for.

Mallory postulated that there is something in man that responds to the challenge of the mountain, and I wonder if that's the case whether there's something in the challenge itself, in the endeavor, and particularly in the big, unfinished, chunky challenges that face humanity that call out to us, and in my experience that's certainly the case. There is one unfinished challenge that's been calling out to me for most of my adult life.

Many of you will know the story. This is a photo of Captain Scott and his team. Scott set out just over a hundred years ago to try to become the first person to reach the South Pole. No one knew what was there. It was utterly unmapped at the time. We knew more about the surface of the moon than we did about the heart of Antarctica. Scott, as many of you will know, was beaten to it by Roald Amundsen and his Norwegian team, who used dogs and dogsleds. Scott's team were on foot, all five of them wearing harnesses and dragging around sledges, and they arrived at the pole to find the Norwegian flag already there, I'd imagine pretty bitter and demoralized. All five of them turned and started walking back to the coast and all five died on that return journey.

There is a sort of misconception nowadays that it's all been done in the fields of exploration and adventure. When I talk about Antarctica, people often say, "Hasn't, you know, that's interesting, hasn't that Blue Peter presenter just done it on a bike?" Or, "That's nice. You know, my grandmother's going on a cruise to Antarctica next year. You know. Is there a chance you'll see her there?" (Laughter)

But Scott's journey remains unfinished. No one has ever walked from the very coast of Antarctica to the South Pole and back again. It is, arguably, the most audacious endeavor of that Edwardian golden age of exploration, and it seemed to me high time, given everything we have figured out in the century since from scurvy to solar panels, that it was high time someone had a go at finishing the job. So that's precisely what I'm setting out to do.

This time next year, in October, I'm leading a team of three. It will take us about four months to make this return journey. That's the scale. The red line is obviously halfway to the pole. We have to turn around and come back again. I'm well aware of the irony of telling you that we will be blogging and tweeting. You'll be able to live vicariously and virtually through this journey in a way that no one has ever before. And it'll also be a four-month chance for me to finally come up with a pithy answer to the question, "Why?"

And our lives today are safer and more comfortable than they have ever been. There certainly isn't much call for explorers nowadays. My career advisor at school never mentioned it as an option. If I wanted to know, for example, how many stars were in the Milky Way, how old those giant heads on Easter Island were, most of you could find that out right now without even standing up. And yet, if I've learned anything in nearly 12 years now of dragging heavy things around cold places, it is that true, real inspiration and growth only comes from adversity and from challenge, from stepping away from what's comfortable and familiar and stepping out into the unknown. In life, we all have tempests to ride and poles to walk to, and I think metaphorically speaking, at least, we could all benefit from getting outside the house a little more often, if only we could sum up the courage. I certainly would implore you to open the door just a little bit and take a look at what's outside. Thank you very much. (Applause)

そりを引くことが私の本来の仕事 知性を問われるなんてことはないですね 今年受けたインタビューの中でこんな質問がありました ”哲学的に継続的な情報の供給は 私達の想像力を奪うのでしょうか? または 達成への期待を取り換えてしまうのでしょうか? 結局は どこかで誰かがやっていることに ネット上で参加が出来るのなら わざわざ家を出る必要があるでしょうか?"

私は極地探検家として 紹介されることが多いです とても今時な肩書きだとは思いませんが 私は人生の2%を北極圏のテントで過ごしています 要は 私はよく外出します 私は本質的に傍観者や思索家ではなく 行動を起こす人間です 今日探っていくのはこの二分性 アイデアとアクションの隔たりです

12年間 ずっと私に付きまとっている ”なぜ?”という質問のもっともな解を見つけたのが 後列 左から2番目のしゃれた紳士 みなさんもご存じかと思いますが ジョージ・リー・マロリーです。 1924年 彼はエベレストの山頂近くで 雲の中に消えていきました 彼がエベレストに登った最初の人間かもしれない エドモンド・ヒラリーの30年以上も前にです 真実は 未だ謎のままですが 「そこに山があるから」という名言を残したとされています 本当に彼がそう言ったのかという 証拠はありません しかし実は 彼は他にもすばらしい言葉を残しているのです 印刷してきたので 読みます

”まず1番はじめに問われて 私が必ず答えなければいけない質問がこれです 何のためにエベレストに登頂するのか? 即答です何のためでもありません 得なんてちっともない 見込もない まぁ 山の上での人間の生命現象について 少しは分かるかもしれません そして 医者たちが 私たちの発見を 航空学に活かしてくれるかもしれません でも メリットはそれぐらいでしょう 金や銀の欠片を持って帰ることもありません 宝石や石炭や鉄もです 耕作できるような土地も見つかりません 本当に何のためにもならない 人間には エベレストからの挑戦に 反応し それに立ち向かう何かがあるということ 上へ上へと登っていかなければならない山の厳しさは 人生の厳しさそのものでもあること それが理解できなければ 山に登る理由なんて 見当たらないでしょう この冒険で手に入るのは最高の喜び 人生を満たす 喜びです 私たちは 稼いだり食べるために生きているのではない これらは人生を楽しむための手段でしかない 人生は楽しむもの楽しむためにあるのです”

マロリーの結論は家を出て冒険に出ると 楽しい 喜びが溢れた体験ができるということです しかし 私の経験とぴったり一致はしません 家から一番遠く離れたのは2004年の春のことでした 未だに 自分の正気を疑いますが 私のプランは 独りで援助なしに 北極海を横断することでした ロシアの北岸から 北極まで歩いて そのまま カナダの北岸に向かう計画でした 史上初への挑戦 当時26歳でした 多くの専門家に不可能だと言われました 母さんもなかなか納得してくれませんでした (笑)

シベリア北岸のある小さな観測所から 最終的な出発点であったパックアイスの端 北極海側の岸まで5時間かかりました 恐れ知らずのフェリックス・バウムガルトナーが スカイダイビングのために気球で上昇するのを見た人ならば 北へと向かうヘリに乗り込み 差し迫った運命のことを考える 私の不安がどんなものだったかおわかりでしょう 自分はなんてことをしているのだと考えていました まだ26歳だった私には 旅を満喫する余裕はありません ヘリからそりを見下ろしていました スキーも衛星電話も シロクマに襲われた時のショットガンもあります 窓の外を眺めていると私たちの2台のヘリは 目を奪うようなシベリアの夜明けのなかを飛んでいました 私の半分は ウィルフレッド・セシジャーと ジェイソン・ボーンをかけ合わせた気分 もう半分は 誇らしい気持ちもありましたが完全にビビッていたことを覚えています

横断の旅は10週間72日間かかりました ずっと1人でしたこの写真はヘリの横で撮ったものです それ以降 10週間誰にも会わなかったのです 北極は広い海の真ん中にあるので 北極海の凍った水面を歩いているわけです NASAの観測史上最悪の天候のなか 180キロの食材・燃料・消耗品を引いて進みました ポンドに換算すると 400ポンドくらいです 10週間の平均気温が-35℃でした-50℃まで下がったこともありました 楽しいことなんて少しもありません

しかし 素敵な体験もありました 私は海の上を歩いていました 北極海を漂流している 氷の塊の上をです 変化が絶えない環境でした 海を漂う氷塊は 崩れてはまた固まり 姿かたちを変え続けます 3か月間 私が目にした景色は私だけのものです 後にも先にも 同じ景色は二度とないのですから これが家から出る最大の理由でしょう 経験を言葉で伝えることはできますが 実際の味わいは分からないでしょう 540万平方マイルの土地に人間が1人 どれほど孤独だったのか -75℃の極寒で襲ってくる雨風その寒さなど 伝えようがないのです伝えきれる言葉がありません 私が思うには 間接的に見たり考えたりするより 自分で行動する つまり 何かを体験し 従事し 挑戦したほうが 人生に充実感が湧き 思う存分に 人生を楽しめるでしょう だが 一つ忠告があります私の経験から言うと 人類の限界ギリギリへの挑戦 この味は知ってしまうと 癖になる これは馬鹿げた エドワード王風の 冒険だけでなく 膵臓がんにも関係あるのです 何かしらの中毒性があるのです 私にとって 極地探索はコカイン中毒と よく似ていると思います 説明できないけど 一度やるとはまってしまう すべての財産を費やし すべての人間関係をダメにしてしまう だから 何をするかには注意が必要だ

人間には 山からの挑戦に立ち向かう ”何か”があるとマロリーは言うが その”何か”は挑戦することそのもの 特に 私たち人類を待ち構えているような 誰も成功したことのない大挑戦に立ち向かうこと その行動にあるのではないかと私は考えます まだケリを付けていない挑戦が 大人になってから ずっと私に付きまとっている

みなさんは この話を知っていると思います これはスコット隊長と探検隊の写真です 彼らは 今から100年ちょっと前に 世界初の南極点到達を目指し出発しました 当時 南極は地図もない未知の世界でした 月に関する知識はあっても 南極については無知でした 知っての通り スコットたちは 犬ぞりを使ったロアール・アムンセン率いるノルウェー隊に 先を越されてしまいましたスコットたちは徒歩で 全員自らそりを引っ張って南極点を目指しました 着いたときには 既にノルウェー旗が刺さっていました ひどい失望を味わったことでしょう 引き返して 海岸へ戻ろうとした帰路で 5人全員が死亡しました

探索や冒険をするところはもうない と 多くの現代人が誤解しています 南極について話していてよく言われるのが 「この前 そこで自転車旅をしている番組見たよ」 とか 「あら!私の祖母は来年 南極クルーズに行くよ もしかして 会うかもね」 とか (笑)

しかし スコットの旅はまだ終わっていない 南極大陸の一番端から南極点まで 徒歩で往復できた人は まだいません おそらく エドワード王の探検黄金時代で もっとも大胆な挑戦だと言えるでしょう 今世紀のなに不自由ない生活 壊血病からソーラー発電まで すべて誰かの挑戦によって 完成した結果なのです だから 私は挑んで行きます

来年の10月 三人のチームを率いて 4か月をかけて往復してみます 縮尺した地図です 赤線が南極点への往路 そして回れ右をして また戻ります 自分が言ったことに矛盾しているかもしれないが 私たちがブログをしたりツイートしたり それにより 今日のネットを通して みなさんも疑似体験ができます そして この4か月の機会に 「なぜ」という質問に答えを見つけ出してきます

こんなに安全で快適な生活を送っている現代 探検家が必要とされていない時代です 学校の進路相談でも 探検家なんて選択肢はなかったです 例えば 天の川にある星の数や イースター島にある モアイ像の年齢を 知りたいと思ったら 座ったままでも すぐに調べることができます しかし 私の12年間にもわたる 寒いところで重い荷物を運ぶ経験から学んだことは 真の感激 成長が 苦労や努力からしか生まれない 快適ないつもの生活から離れ 未知の世界に踏み込んで手に入るものです 誰にだって人生で 乗り越えるべき壁やたどり着くべき目標があります 比喩的な話ではありますが 勇気を出して 家の外に出る回数を 少し増やすだけでなにか得ることがあるはずです ドアを開け 外の世界を探索しましょう それは 私からのお願いです ありがとうございました (拍手)

品詞分類

- 主語

- 動詞

- 助動詞

- 準動詞

- 関係詞等

TED 日本語

TED Talks

関連動画

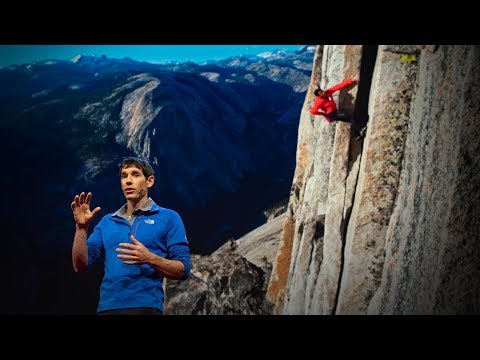

900メートルの絶壁をいかにしてロープなしで登ったのかアレックス・オノルド

2018.10.29

ジェット・スーツができるまでリチャード・ブラウニング

2017.07.17

成層圏からのジャンプ、それをお話ししますアラン・ユースタス

2015.09.28

私が世界一周単独航海で学んだ意外なことデイム・エレン・マッカーサー

おすすめ 22015.06.29

最後の手つかずの大陸を守れロバート・スワン

2015.01.13

南極点に行って戻る ― 人生で最も厳しい105日間ベン・サンダース

2014.12.02

夢は決してあきらめるなダイアナ・ナイアド

おすすめ 32013.12.23

綱を渡る旅フィリップ・プティ

2012.05.23

世界一危険なクラゲに出会った 私のエクストリームスイムダイアナ・ナイアド

2012.01.24

空駆けるジェットマンイブ・ロッシー

2011.11.15

意識を変えるためのエベレスト水泳ルイス・ピュー

2010.07.30

私が太平洋を漕いで横断する理由ロズ・サベージ

2010.04.28

エベレストにて、奇跡の生還ケン・カムラー

2010.03.18

17分間の息止め世界記録デイビッド・ブレイン

2010.01.19

北極海での水泳ルイス・ピュー

2009.09.09

スカイダイビング世界記録への挑戦スティーブ・トルグリア

2009.09.07

洋楽 おすすめ

RECOMMENDS

洋楽歌詞

ステイザ・キッド・ラロイ、ジャスティン・ビーバー

洋楽最新ヒット2021.08.20

スピーチレス~心の声ナオミ・スコット

洋楽最新ヒット2019.05.23

シェイプ・オブ・ユーエド・シーラン

洋楽人気動画2017.01.30

フェイデッドアラン・ウォーカー

洋楽人気動画2015.12.03

ウェイティング・フォー・ラヴアヴィーチー

洋楽人気動画2015.06.26

シー・ユー・アゲインウィズ・カリファ

洋楽人気動画2015.04.06

シュガーマルーン5

洋楽人気動画2015.01.14

シェイク・イット・オフテイラー・スウィフト

ポップス2014.08.18

オール・アバウト・ザット・ベースメーガン・トレイナー

ポップス2014.06.11

ストーリー・オブ・マイ・ライフワン・ダイレクション

洋楽人気動画2013.11.03

コール・ミー・メイビーカーリー・レイ・ジェプセン

洋楽人気動画2012.03.01

美しき生命コールドプレイ

洋楽人気動画2008.08.04

バッド・デイ~ついてない日の応援歌ダニエル・パウター

洋楽人気動画2008.05.14

サウザンド・マイルズヴァネッサ・カールトン

洋楽人気動画2008.02.19

イッツ・マイ・ライフボン・ジョヴィ

ロック2007.10.11

アイ・ウォント・イット・ザット・ウェイバックストリート・ボーイズ

洋楽人気動画2007.09.14

マイ・ハート・ウィル・ゴー・オンセリーヌ・ディオン

洋楽人気動画2007.07.12

ヒーローマライア・キャリー

洋楽人気動画2007.03.21

オールウェイズ・ラヴ・ユーホイットニー・ヒューストン

洋楽人気動画2007.02.19

オネスティビリー・ジョエル

洋楽人気動画2005.09.16