TED日本語

TED Talks(英語 日本語字幕付き動画)

TED日本語 - アンドリュー・ソロモン: 揺るぎなき愛

TED Talks

揺るぎなき愛

Love, no matter what

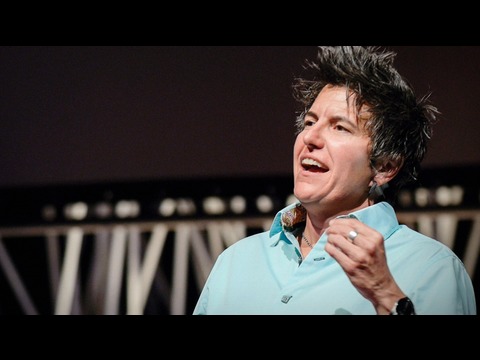

アンドリュー・ソロモン

Andrew Solomon

内容

自分と根本的に異質な子供(例えば天才児、あるいは特異な才能を持った子供や犯罪に手を染めた子供など)を育てるというのは、どのようなことなのでしょうか?この静かに進行するトークの中で、作家のアンドリュー・ソロモンは何十組もの親たちとの対話を通して学んだことを語ります。無条件の愛と無条件の受容とは何が異なるのでしょうか?

字幕

SCRIPT

Script

"Even in purely non-religious terms, homosexuality represents a misuse of the sexual faculty. It is a pathetic little second-rate substitute for reality -- a pitiable flight from life. As such, it deserves no compassion, it deserves no treatment as minority martyrdom, and it deserves not to be deemed anything but a pernicious sickness."

That's from Time magazine in 1966, when I was three years old. And last year, the president of the United States came out in favor of gay marriage.

(Applause)

And my question is, how did we get from there to here? How did an illness become an identity?

When I was perhaps six years old, I went to a shoe store with my mother and my brother. And at the end of buying our shoes, the salesman said to us that we could each have a balloon to take home. My brother wanted a red balloon, and I wanted a pink balloon. My mother said that she thought I'd really rather have a blue balloon. But I said that I definitely wanted the pink one. And she reminded me that my favorite color was blue. The fact that my favorite color now is blue, but I'm still gay -- (Laughter) -- is evidence of both my mother's influence and its limits.

(Laughter)

(Applause)

When I was little, my mother used to say, "The love you have for your children is like no other feeling in the world. And until you have children, you don't know what it's like." And when I was little, I took it as the greatest compliment in the world that she would say that about parenting my brother and me. And when I was an adolescent, I thought that I'm gay, and so I probably can't have a family. And when she said it, it made me anxious. And after I came out of the closet, when she continued to say it, it made me furious. I said, "I'm gay. That's not the direction that I'm headed in. And I want you to stop saying that."

About 20 years ago, I was asked by my editors at The New York Times Magazine to write a piece about deaf culture. And I was rather taken aback. I had thought of deafness entirely as an illness. Those poor people, they couldn't hear. They lacked hearing, and what could we do for them? And then I went out into the deaf world. I went to deaf clubs. I saw performances of deaf theater and of deaf poetry. I even went to the Miss Deaf America contest in Nashville, Tennessee where people complained about that slurry Southern signing.

(Laughter)

And as I plunged deeper and deeper into the deaf world, I become convinced that deafness was a culture and that the people in the deaf world who said, "We don't lack hearing, we have membership in a culture," were saying something that was viable. It wasn't my culture, and I didn't particularly want to rush off and join it, but I appreciated that it was a culture and that for the people who were members of it, it felt as valuable as Latino culture or gay culture or Jewish culture. It felt as valid perhaps even as American culture.

Then a friend of a friend of mine had a daughter who was a dwarf. And when her daughter was born, she suddenly found herself confronting questions that now began to seem quite resonant to me. She was facing the question of what to do with this child. Should she say, "You're just like everyone else but a little bit shorter?" Or should she try to construct some kind of dwarf identity, get involved in the Little People of America, become aware of what was happening for dwarfs?

And I suddenly thought, most deaf children are born to hearing parents. Those hearing parents tend to try to cure them. Those deaf people discover community somehow in adolescence. Most gay people are born to straight parents. Those straight parents often want them to function in what they think of as the mainstream world, and those gay people have to discover identity later on. And here was this friend of mine looking at these questions of identity with her dwarf daughter. And I thought, there it is again: A family that perceives itself to be normal with a child who seems to be extraordinary. And I hatched the idea that there are really two kinds of identity.

There are vertical identities, which are passed down generationally from parent to child. Those are things like ethnicity, frequently nationality, language, often religion. Those are things you have in common with your parents and with your children. And while some of them can be difficult, there's no attempt to cure them. You can argue that it's harder in the United States -- our current presidency notwithstanding -- to be a person of color. And yet, we have nobody who is trying to ensure that the next generation of children born to African-Americans and Asians come out with creamy skin and yellow hair.

There are these other identities which you have to learn from a peer group. And I call them horizontal identities, because the peer group is the horizontal experience. These are identities that are alien to your parents and that you have to discover when you get to see them in peers. And those identities, those horizontal identities, people have almost always tried to cure.

And I wanted to look at what the process is through which people who have those identities come to a good relationship with them. And it seemed to me that there were three levels of acceptance that needed to take place. There's self-acceptance, there's family acceptance, and there's social acceptance. And they don't always coincide.

And a lot of the time, people who have these conditions are very angry because they feel as though their parents don't love them, when what actually has happened is that their parents don't accept them. Love is something that ideally is there unconditionally throughout the relationship between a parent and a child. But acceptance is something that takes time. It always takes time.

One of the dwarfs I got to know was a guy named Clinton Brown. When he was born, he was diagnosed with diastrophic dwarfism, a very disabling condition, and his parents were told that he would never walk, he would never talk, he would have no intellectual capacity, and he would probably not even recognize them. And it was suggested to them that they leave him at the hospital so that he could die there quietly.

And his mother said she wasn't going to do it. And she took her son home. And even though she didn't have a lot of educational or financial advantages, she found the best doctor in the country for dealing with diastrophic dwarfism, and she got Clinton enrolled with him. And in the course of his childhood, he had 30 major surgical procedures. And he spent all this time stuck in the hospital while he was having those procedures, as a result of which he now can walk.

And while he was there, they sent tutors around to help him with his school work. And he worked very hard because there was nothing else to do. And he ended up achieving at a level that had never before been contemplated by any member of his family. He was the first one in his family, in fact, to go to college, where he lived on campus and drove a specially-fitted car that accommodated his unusual body.

And his mother told me this story of coming home one day -- and he went to college nearby -- and she said, "I saw that car, which you can always recognize, in the parking lot of a bar," she said. (Laughter) "And I thought to myself, they're six feet tall, he's three feet tall. Two beers for them is four beers for him." She said, "I knew I couldn't go in there and interrupt him, but I went home, and I left him eight messages on his cell phone." She said, "And then I thought, if someone had said to me when he was born that my future worry would be that he'd go drinking and driving with his college buddies -- "

(Applause)

And I said to her, "What do you think you did that helped him to emerge as this charming, accomplished, wonderful person?" And she said, "What did I do? I loved him, that's all. Clinton just always had that light in him. And his father and I were lucky enough to be the first to see it there."

I'm going to quote from another magazine of the '60s. This one is from 1968 -- The Atlantic Monthly, voice of liberal America -- written by an important bioethicist. He said, "There is no reason to feel guilty about putting a Down syndrome child away, whether it is put away in the sense of hidden in a sanitarium or in a more responsible, lethal sense. It is sad, yes -- dreadful. But it carries no guilt. True guilt arises only from an offense against a person, and a Down's is not a person."

There's been a lot of ink given to the enormous progress that we've made in the treatment of gay people. The fact that our attitude has changed is in the headlines every day. But we forget how we used to see people who had other differences, how we used to see people who were disabled, how inhuman we held people to be. And the change that's been accomplished there, which is almost equally radical, is one that we pay not very much attention to.

One of the families I interviewed, Tom and Karen Robards, were taken aback when, as young and successful New Yorkers, their first child was diagnosed with Down syndrome. They thought the educational opportunities for him were not what they should be, and so they decided they would build a little center -- two classrooms that they started with a few other parents -- to educate kids with D.S. And over the years, that center grew into something called the Cooke Center, where there are now thousands upon thousands of children with intellectual disabilities who are being taught.

In the time since that Atlantic Monthly story ran, the life expectancy for people with Down syndrome has tripled. The experience of Down syndrome people includes those who are actors, those who are writers, some who are able to live fully independently in adulthood.

The Robards had a lot to do with that. And I said, "Do you regret it? Do you wish your child didn't have Down syndrome? Do you wish you'd never heard of it?" And interestingly his father said, "Well, for David, our son, I regret it, because for David, it's a difficult way to be in the world, and I'd like to give David an easier life. But I think if we lost everyone with Down syndrome, it would be a catastrophic loss."

And Karen Robards said to me, "I'm with Tom. For David, I would cure it in an instant to give him an easier life. But speaking for myself -- well, I would never have believed 23 years ago when he was born that I could come to such a point -- speaking for myself, it's made me so much better and so much kinder and so much more purposeful in my whole life, that speaking for myself, I wouldn't give it up for anything in the world."

We live at a point when social acceptance for these and many other conditions is on the up and up. And yet we also live at the moment when our ability to eliminate those conditions has reached a height we never imagined before. Most deaf infants born in the United States now will receive Cochlear implants, which are put into the brain and connected to a receiver, and which allow them to acquire a facsimile of hearing and to use oral speech. A compound that has been tested in mice, BMN-111, is useful in preventing the action of the achondroplasia gene. Achondroplasia is the most common form of dwarfism, and mice who have been given that substance and who have the achondroplasia gene, grow to full size. Testing in humans is around the corner. There are blood tests which are making progress that would pick up Down syndrome more clearly and earlier in pregnancies than ever before, making it easier and easier for people to eliminate those pregnancies, or to terminate them.

And so we have both social progress and medical progress. And I believe in both of them. I believe the social progress is fantastic and meaningful and wonderful, and I think the same thing about the medical progress. But I think it's a tragedy when one of them doesn't see the other. And when I see the way they're intersecting in conditions like the three I've just described, I sometimes think it's like those moments in grand opera when the hero realizes he loves the heroine at the exact moment that she lies expiring on a divan.

(Laughter)

We have to think about how we feel about cures altogether. And a lot of the time the question of parenthood is, what do we validate in our children, and what do we cure in them?

Jim Sinclair, a prominent autism activist, said, "When parents say 'I wish my child did not have autism,' what they're really saying is 'I wish the child I have did not exist and I had a different, non-autistic child instead.' Read that again. This is what we hear when you mourn over our existence. This is what we hear when you pray for a cure -- that your fondest wish for us is that someday we will cease to be and strangers you can love will move in behind our faces." It's a very extreme point of view, but it points to the reality that people engage with the life they have and they don't want to be cured or changed or eliminated. They want to be whoever it is that they've come to be.

One of the families I interviewed for this project was the family of Dylan Klebold who was one of the perpetrators of the Columbine massacre. It took a long time to persuade them to talk to me, and once they agreed, they were so full of their story that they couldn't stop telling it. And the first weekend I spent with them -- the first of many -- I recorded more than 20 hours of conversation.

And on Sunday night, we were all exhausted. We were sitting in the kitchen. Sue Klebold was fixing dinner. And I said, "If Dylan were here now, do you have a sense of what you'd want to ask him?" And his father said, "I sure do. I'd want to ask him what the hell he thought he was doing." And Sue looked at the floor, and she thought for a minute. And then she looked back up and said, "I would ask him to forgive me for being his mother and never knowing what was going on inside his head."

When I had dinner with her a couple of years later -- one of many dinners that we had together -- she said, "You know, when it first happened, I used to wish that I had never married, that I had never had children. If I hadn't gone to Ohio State and crossed paths with Tom, this child wouldn't have existed and this terrible thing wouldn't have happened. But I've come to feel that I love the children I had so much that I don't want to imagine a life without them. I recognize the pain they caused to others, for which there can be no forgiveness, but the pain they caused to me, there is," she said. "So while I recognize that it would have been better for the world if Dylan had never been born, I've decided that it would not have been better for me."

I thought it was surprising how all of these families had all of these children with all of these problems, problems that they mostly would have done anything to avoid, and that they had all found so much meaning in that experience of parenting. And then I thought, all of us who have children love the children we have, with their flaws. If some glorious angel suddenly descended through my living room ceiling and offered to take away the children I have and give me other, better children -- more polite, funnier, nicer, smarter -- I would cling to the children I have and pray away that atrocious spectacle. And ultimately I feel that in the same way that we test flame-retardant pajamas in an inferno to ensure they won't catch fire when our child reaches across the stove, so these stories of families negotiating these extreme differences reflect on the universal experience of parenting, which is always that sometimes you look at your child and you think, where did you come from?

(Laughter)

It turns out that while each of these individual differences is siloed -- there are only so many families dealing with schizophrenia, there are only so many families of children who are transgender, there are only so many families of prodigies -- who also face similar challenges in many ways -- there are only so many families in each of those categories -- but if you start to think that the experience of negotiating difference within your family is what people are addressing, then you discover that it's a nearly universal phenomenon. Ironically, it turns out, that it's our differences, and our negotiation of difference, that unite us.

I decided to have children while I was working on this project. And many people were astonished and said, "But how can you decide to have children in the midst of studying everything that can go wrong?" And I said, "I'm not studying everything that can go wrong. What I'm studying is how much love there can be, even when everything appears to be going wrong."

I thought a lot about the mother of one disabled child I had seen, a severely disabled child who died through caregiver neglect. And when his ashes were interred, his mother said, "I pray here for forgiveness for having been twice robbed, once of the child I wanted and once of the son I loved." And I figured it was possible then for anyone to love any child if they had the effective will to do so.

So my husband is the biological father of two children with some lesbian friends in Minneapolis. I had a close friend from college who'd gone through a divorce and wanted to have children. And so she and I have a daughter, and mother and daughter live in Texas. And my husband and I have a son who lives with us all the time of whom I am the biological father, and our surrogate for the pregnancy was Laura, the lesbian mother of Oliver and Lucy in Minneapolis.

(Applause)

So the shorthand is five parents of four children in three states.

And there are people who think that the existence of my family somehow undermines or weakens or damages their family. And there are people who think that families like mine shouldn't be allowed to exist. And I don't accept subtractive models of love, only additive ones. And I believe that in the same way that we need species diversity to ensure that the planet can go on, so we need this diversity of affection and diversity of family in order to strengthen the ecosphere of kindness.

The day after our son was born, the pediatrician came into the hospital room and said she was concerned. He wasn't extending his legs appropriately. She said that might mean that he had brain damage. In so far as he was extending them, he was doing so asymmetrically, which she thought could mean that there was a tumor of some kind in action. And he had a very large head, which she thought might indicate hydrocephalus.

And as she told me all of these things, I felt the very center of my being pouring out onto the floor. And I thought, here I had been working for years on a book about how much meaning people had found in the experience of parenting children who are disabled, and I didn't want to join their number. Because what I was encountering was an idea of illness. And like all parents since the dawn of time, I wanted to protect my child from illness. And I wanted also to protect myself from illness. And yet, I knew from the work I had done that if he had any of the things we were about to start testing for, that those would ultimately be his identity, and if they were his identity they would become my identity, that that illness was going to take a very different shape as it unfolded.

We took him to the MRI machine, we took him to the CAT scanner, we took this day-old child and gave him over for an arterial blood draw. We felt helpless. And at the end of five hours, they said that his brain was completely clear and that he was by then extending his legs correctly. And when I asked the pediatrician what had been going on, she said she thought in the morning he had probably had a cramp.

(Laughter)

But I thought how my mother was right. I thought, the love you have for your children is unlike any other feeling in the world, and until you have children, you don't know what it feels like.

I think children had ensnared me the moment I connected fatherhood with loss. But I'm not sure I would have noticed that if I hadn't been so in the thick of this research project of mine. I'd encountered so much strange love, and I fell very naturally into its bewitching patterns. And I saw how splendor can illuminate even the most abject vulnerabilities.

During these 10 years, I had witnessed and learned the terrifying joy of unbearable responsibility, and I had come to see how it conquers everything else. And while I had sometimes thought the parents I was interviewing were fools, enslaving themselves to a lifetime's journey with their thankless children and trying to breed identity out of misery, I realized that day that my research had built me a plank and that I was ready to join them on their ship.

Thank you.

(Applause)

「宗教的なことは一切 抜きにしても ホモセクシャルは性的機能の 誤用と言わざるを得ない それは救いようのない 低俗な現実の代用品であり 人生からの哀れむべき逃避である それ自体 同情には値せず マイノリティの苦難として 治療にも値しない 不治の病と見なすより他にない」

これは1966年 私が3歳の時に発行された TIME誌からの引用です そして昨年 アメリカ合衆国大統領は 同性婚に好意的な態度を表明しました

(拍手)

ここまでの道程は どんなものだったのでしょう いかにして「病」は アイデンティティになったのでしょう

私が6歳ぐらいだった時のことです 母と弟と一緒に 靴屋へ行きました 靴を買った後 お店の人が風船をくれると言いました 弟は赤い風船を 私はピンクの風船を希望しました 母は私に「本当は青がいいんでしょ?」 と言いました でも私は絶対に ピンクが良かったのです 母は 「青色が好きだったでしょう」と 念押ししました 現在の私は青が好きですが 相変わらずゲイですから ― (笑) これは母親の影響力と その限界を 同時に証明している訳です

(笑)

(拍手)

小さい頃 母はよく言っていました 「子供に対する親の愛情は 他のどんな感情にも代えがたいものよ 子供を持ってみないと わからないけどね」 私たち兄弟を育てることを そんなふうに言ってくれる ― 幼い私にとって 母の言葉は最大の賛辞でした 思春期になり 私は自分がゲイで おそらく家族を持つことはないと 思うようになりました すると母の言葉は 私を不安にさせました カミングアウト後も 母は例のセリフを言い続け 私は怒りを覚えました 「僕はゲイだから その方向へは進まない」 「もう言わないでくれ」と言いました

20年ほど前 私はニューヨーク・ タイムズ・マガジンの編集者から ろう文化についての記事を 依頼されました かなり戸惑いました 「ろう」を全くの疾患と思っていたのです 耳の聞こえない 気の毒な人々 聴覚のない彼らのために 何ができるのか? やがて私は ろうの世界に入り ろう者のクラブに行きました ろう者の演劇や手話詩を 見に行きました テネシー州ナッシュビルで開催された ろう者のミスコンにも行ったのですが そこでは皆「南部の手話は訛っている」 と文句を言っていました

(笑)

ろう者の世界に どんどん深く はまって行き 私は ろう が文化であると 確信しました ろう者たちの 「我々は聴覚がないんじゃない この文化を担う 権利を持ってるんだ」という言葉に たくましさを感じました 私は部外者でしたし その文化に殊更 入りたいとも思っていませんでしたが 私はそれが一つの文化であり その文化のメンバーたちにとっては ラテン文化やゲイ文化 ユダヤ文化と同様 価値のあるものなんだと感じました 仮に アメリカ文化と比べても 引けを取らないでしょう

同じ頃 友達の友達に 小人症の娘が生まれました 娘が生まれると同時に 母親の目の前には 疑問が立ちはだかりました それは今の私には とても共感できることです 「この子と どう向き合えばいいのか?」 という疑問です 「あなたは ちょっと小さいけど 他の皆と同じなのよ」と言うのか? それとも 小人としての アイデンティティの確立を目指し Little People of America に参加して 小人症の現状に目を向けるべきか?

私は突然 思いつきました ろうの子の殆どは 健常の親の元に生まれます 親たちは「治療」を考えがちですが 子供は思春期になると ろうのコミュニティを発見するものです 同性愛者の殆どは ストレートの親の元に生まれます ストレートの親は大抵 自分たちの考える「普通」の世界で 生きていけるようになってほしい と望みますが 同性愛者は自らのアイデンティティを いずれ発見することになります いま私の友人が直面しているのは 小人症の娘の アイデンティティの問題です 同じだと思いました どこか普通でない子を持ちながらも そのことを普通だと捉えている家族 私はアイデンティティには 2種類あると考えるようになりました

1つは「縦」のアイデンティティ これは親から子へ 受け継がれていくもので 民族性や 多くの場合 国民性 言語や宗教などのことです これらは親子間で 共有されるアイデンティティです 中には厳しいものもありますが 誰もそれを「治療」しようとはしません 現大統領が有色とはいえ やはりアメリカ合衆国において 有色人種であることは 困難を伴うと言えるでしょう だからと言って アフリカ系アメリカ人や アジア人の間に生まれる 次世代の子供たちの肌をクリーム色に 髪を黄色にしてやろうと思う人は どこにもいません

これとは別に仲間から学ぶ アイデンティティがあります 仲間というのは 横に広がる感覚ですから 私はこれを 「横」のアイデンティティと呼びます このアイデンティティについて 親は門外漢ですから 仲間との関わりから 見つけるしかないのです このような横のアイデンティティは ほとんどの場合 「治療」の対象にされます

私はこうしたアイデンティティを 持つ人々が それらと上手く 付き合えるようになるまでの 過程を調べたいと考えました どうやら その過程では もれなく3段階の受容が 生じるようでした それは 自己による受容 家族による受容 そして社会による受容です 同時に起きるとは限りません

こうした状況にある人は大抵 怒りに満ちています 彼らが親に愛されていないと 感じているためですが 実は親は 彼らを受容できていないだけなのです 愛は 理想的に言えば 親子の間で 常に 無条件に存在するものです しかし受容には時間がかかります 時間がかかるものなのです

知り合いの小人症の男性に クリントン・ブラウンという人がいました 彼は生まれた時に 変形性小人症で ― 重度の障害と診断されました 両親は こう告げられました 彼は歩くことも話すこともできず 知能も持たず おそらく親を認識することすら ないだろうと そして彼が静かに息を引き取れるよう 病院に置いていくことを 勧められました

ところが彼の母は きっぱり断り 彼を家に連れて帰ったのです 教育の面でも経済的にも 余裕はありませんでしたが 変形小人症に立ち向かうために 母親は 国内で最高の医者を見つけ出し クリントンを そこへ入院させました 彼は幼少期のうちに 30回の大手術を受けました 彼はその間のすべての時間を 病院で過ごしましたが おかげで歩けるようになりました

入院中も学校の勉強ができるように 親は家庭教師を雇いました 他にすることもないので 彼は一生懸命勉強しました そして ついに彼は 家族の誰もが予期しなかった程の レベルに到達したのです 彼は家族の中で大学に進んだ 第1号となり キャンパスに住み 彼の特別な体に合わせた ― 特別装備の車を運転しました

彼の母がこんな話をしてくれました ある日の帰宅途中のこと 彼の大学は近所にあるのですが 「あの子の車は 見たらすぐにわかるでしょ それがバーの駐車場にあったのよ」 (笑) 「他の人たちは身長180センチ 彼は90センチだから 2杯のビールは 彼には4杯分ってことよ」 「そこへ割り込んで行くわけにも いかないし 家に帰って 彼の携帯に 8回も留守電を入れちゃった」 「その時 思ったの 彼が生まれた時に 『いずれは大学の仲間と車で飲みに行って 心配させられることになるよ』 なんて言う人がいたかしら」

(拍手)

彼女に尋ねました 「彼がここまで魅力的で ― 優秀で素晴らしい人間になったのは あなたが何をしたからでしょう?」 彼女は言いました「私が何をしたか? 私は彼を愛してた ただそれだけよ クリントンは輝く素質のある子でした 夫と私はそれを誰よりも先に見られて 幸運でした」

ここでまた60年代の別の雑誌から 引用を紹介します 1968年のアトランティック誌からです 自由主義アメリカの声として ある生命倫理学の重鎮が書きました 「ダウン症の子供を捨てたとしても 何ら罪を感じる必要はない 施設に こっそり捨てようと もっと責任を問われるような 命に関わる捨て方だろうと それは悲しく厭な事ではあるが 罪を伴うことではない 罪とは 人間に対して犯すものに 限られるが ダウン症は人間ではない」

ゲイに対する待遇が 大きく進展したことについては 多くの言説が公になっています ゲイに対する態度が変化したことを 日々マスコミが取り上げています ところが私たちは他の違いを持つ人々を 過去にどういう目で見ていたか 障害者を どう見ていたのか 人々をいかに残酷な生き物にしてきたか 忘れていました 今日達成された変化は ゲイと同程度に急進的ですが 私たちは十分に注意を 払ってきませんでした

私が取材した家族の中に トム&カレン・ロバーズがいます 若くして成功したニューヨーカーである 夫妻は非常に驚きました 初めての子供がダウン症と 診断されたのです 夫妻は息子に用意された教育が 適切なものではないと考え 自らの手で小さな教育センターを 作る決意をしました 他の親たちと一緒に2つの教室を作り ダウン症の子の教育を始めました やがて拡大し「クック・センター」と 呼ばれるまでになり 今や何千もの知的障害を持つ子たちが そこで教育を受けています

例のアトランティック誌の記事掲載から 今日までに ダウン症の人々の平均余命は 3倍になりました ダウン症の人々の中には 役者になったり 作家になったり 完全に独立した成人として 生活できている人もいます

ロバーズ夫妻の功績です 夫妻に尋ねました 「悔いはありますか?」 「我が子がダウン症でなかったらと 思いますか? ダウン症と縁のない人生を 望みますか?」 父親の答えは興味深いものでした 「息子のデビッドに関しては 悔いがあります デビッドにとっては 生き辛くさせていますからね 息子には もっと楽な生き方を させてあげたかった でも もしダウン症の子を皆 失ったら それは とてつもない損失です」

カレン・ロバーズは言いました 「私もトムと同じです 息子に関しては すぐにでも治して もっと楽に生きられるようにしてあげたい だけど 自分に関して言えば デビッドが生まれた23年前には 考えられなかったことだけど 私自身は ダウン症と関わって ずっと親切で良い人間になれたし はっきり目的を持って 生きられるようになったわ だから私に関して言えば 悔いは何一つありません」

ダウン症を含む様々な障害が 確実に社会で受容される時代に 私たちは生きています そして同時に この時代は その障害を取り除くための 我々の能力も かつて想像できなかった程の レベルに達しています 今日 アメリカで ろうで生まれた子の ほとんどは 人工内耳の手術が受けられます 人工内耳を脳に埋め込み 受信機と接続することで 彼らは電送によって聞き 発語できるようになります すでにマウス実験を終えた BMN-111という治験薬は 軟骨発育不全症の遺伝子の作用を 防ぐのに効果があります 軟骨発育不全は小人症の原因として 最も多いものですが 軟骨発育不全の遺伝子を持つマウスに その薬を与えると 通常のサイズに成長します 人間への臨床試験まで あと少しです ダウン症の胎児をより正確に かつてないほど早い段階で判定できる 血液検査も進歩しています これにより妊娠中絶を望む場合には より簡単に できるようになります

このように社会的にも医学的にも 進歩があります 私はどちらも大切なことだと思います 社会的な進歩は素敵なことですし 有意義で素晴らしいと思います 医学的な進歩も同様に 素晴らしいと考えています しかし 双方の思惑がすれ違っていては 悲劇です 私が挙げた3つの障害を取り巻く環境で 2つの進歩が交差する様子は まるでグランド・オペラの一幕のようだと 思うことがあります 主人公がヒロインを愛していると悟った まさにその時 ヒロインは横たわり息を引き取るという あの場面です

(笑)

私たちは 治療に対する感情について 一緒に考えなくてはなりません 親の立場から いつも問題となるのは 自分たちの子供の何に 価値を見出すのか 子供の何を治すのかということです

ジム・シンクレアという有名な 自閉症の活動家がこう言っています 「親が 『うちの子に自閉症がなければ 良かったのに』と言ったら それは 『この子が生まれてこなかったら 良かったのに そして代わりに ― 自閉症でない子供がほしかった』と 言っているのと同じです」 「よく考えてください 私たちの存在を 嘆いているように聞こえるのですよ あなた方が私たちの治癒を願う時 私たちは こう感じています あなた方の一番の願いは 私たちの存在がなくなり その中身だけが あなた方の愛せる知らない誰かと こっそり入れ替わることなのだと」 これは非常に極端な物の見方ですが 障害を持つ人々が人生で直面している 現実を示しています 彼らは治癒も変化も 障害の除去も 望んではいないのです どんな境遇であれ 彼らは自分のままでありたいのです

このプロジェクトのために インタビューした家族の中に コロンバイン高校の虐殺犯の一人 ディラン・クレボルドの家族がいました 話してくれるよう説得するには 長い時間がかかりましたが 一旦了解すると 彼らからは 様々な話が溢れ出し 止めどもなく 語ってくれました 週末ごとに何度も 彼らに会いましたが その初回だけでも 20時間以上の会話を録音しました

日曜の夜には全員 疲れ果てていました 私たちは台所に座り スー・クレボルドは 晩御飯の支度中でした 私は尋ねました 「もしディランが今ここに居たら 彼に何か聞きたいという気持ちは ありますか?」 父親はこう答えました 「もちろんです どういうつもりで あんな事をしでかしたか 聞いてやりたいです」 スーは床を見つめて しばらく考えていました 顔を上げると 彼女はこう言いました 「私は母親でありながら 彼の内面で何が起きているのか 分かってあげられなかったことを 許してと言いたいわ」

数年後 彼女と夕食を とっていた時のことです 何度も ご一緒したうちの一回です 彼女は言いました 「あの事件があった時 私は結婚して子供を持ったことを とても悔やんでいたわ もし私がオハイオ州立大に行かず トムと出会わなければ あの子は生まれてこなかったし あの悲惨な事件も起きなかったでしょう でも ようやく私は子供たちを とても愛していたと思えるようになったの 子供たち抜きの人生なんて 想像できないわ あの子達が他の人に与えた苦しみは 決して許されるものではありません でも 私の苦しみに限っては 許してやろうと思うの」 「だから もしディランが 生まれてこなかったとしたら 世の中にとって良かったとは思うけど 私にとっては そうではなかったと 思うことに決めたの」

驚くべきことだと思いました 様々な問題のある子供を持つ家族は皆 大抵 その問題を何とか回避しようとし そこで親として経験したことに とても大きな意義を見出しているのです そして私は 子供を持つ全ての親は その欠陥も含めて我が子を 愛しているのだと思いました もしも突然 美しい天使が リビングの天井から舞い降りて来て 私の子供を取り上げる代わりに もっと良い子供 ― 礼儀正しくて 愉快で 素直で 賢い子供をあげると言われたら 私は我が子に しがみついて その最悪な状況が過ぎ去るよう祈るでしょう こうした感情は 結局のところ 我が子がストーブに手を伸ばした時 火がつかないように 燃えないパジャマを 念のため火にくべてみるのと同じです 乗り越えてきた違いは極端でも これらの家族のストーリーは 万国共通の親心の表れであって 親が子供の顔を見て ふと思う あの感慨と同じです 「あなたはどこから来たの?」

(笑)

それぞれの違いは個別で それ自体に関連性はありませんから ある家族は統合失調症に取り組み ある家族はトランスジェンダーの子を持つ という具合ですが 天才児を抱えた家族にしても 直面する困難としては よく似ています 各カテゴリーに分類される家族の 数は限られるものの 家族の間で生じた違いに ― 折り合いをつけていく経験を 他の人々も取り組んでいるのだと 考えるようにすれば それが ごく一般的な現象であることに 気づくでしょう 皮肉なことですが 違いがあり その違いに折り合いをつけていくからこそ 私たちの間に 結びつきが生まれるのです

このプロジェクトに取り組みながら 私は 自分も子供を持つことを決心しました 多くの人たちは驚いて こう言いました 「子育ての大変さを調査している最中に よく子供を持とうと思ったね」 こう返しました 「私は大変さを 調査しているんじゃないですよ 私が調査しているのは ものすごく大変そうな中に いかに たくさんの愛が存在しているか ということです」

私は障害児を持った ある母親のことを よく考えました その子は重度の障害児で 介護者のネグレクトによって亡くなりました 遺灰を埋める時 母親はこう言いました 「2度に渡って奪われた罪を お赦しいただきたく 祈ります 一度は私が望んだ子 そして もう一度は私が愛した子を」 それを聞き私は 強い意志さえあれば どんな人でも どんな子でも 愛することが可能なのだと気づきました

私の夫には ミネアポリスに住む レズビアンの友人との間に 血のつながった子が2人います 私には 大学からの親友で 離婚を経て 子供が欲しくなった女性がいて 彼女と私の間に娘がいます 彼女と娘はテキサスで暮らしています 夫と私にはずっと一緒に暮らしている 息子がいますが 息子と私は血がつながっています 代理母になってくれたのはローラという ミネアポリスに住むレズビアンで 彼女にはオリバーとルーシーという 子供がいます

(拍手)

要約すると 3つの州に 4人の子供の親が5人いるわけです

こんな家族が存在すると 自分たちの家族が傷つけられたり 弱体化させられたり 害を与えられると 考える人々がいます 私の家族のようなものの存在は 許されるべきでないと 考える人々もいます 私は 引き算の愛は認めません 認めるのは足し算の愛のみです この星が確実に存続していくために 種の多様性が必要なように 優しさの生態圏を強化するために 私たちには愛情の多様性と 家族の多様性が必要なのです

息子が生まれた翌日 小児科医が病室に入ってきて 気になることがあると言いました 息子の足の伸ばし方が おかしいと言うのです 脳に障害があるかもしれないと いうことでした 確かに彼の足の伸ばし方は 左右対称ではなく それで医者は何らかの腫瘍のせい ではないかと考えたのです 更に彼は頭がとても大きく 医者は 水頭症の兆候かもしれないと考えました

医者の説明を聞いて 私は 自分の中心が 床の上に 溢れ出すような感覚を覚えました それまでの仕事で 私は 障害児を育てる経験を通して 人々が感得する意義について 執筆していながら 自分は仲間に入りたくないと思いました 私が直面していたのは 病気という観念だったからです 歴史開闢以来 どの親もそうであるように 私は我が子を 病気から守りたいと思いました 私自身も病気から 身を守りたいと思いました 同時に 私は自分の仕事を通じて これから検査をして 息子に何らかの 問題があったとしても 結局はそれが この子の アイデンティティとなり だとすれば それは 私のアイデンティティにもなるのだと その病気はこの先 大きく形を 変えていくのだと 知っていました

私たちは息子を MRI や CT にかけ 生後1日の我が子に 動脈血の検査を受けさせました 無力感を味わいました そして5時間が経過した後 医者たちは彼の脳には何の問題もなく 足の伸ばし方も良くなったと言いました 私が小児科医に何が起きたのか尋ねると こんな答えでした 「朝 痙攣を起こしたせいかしらね」

(笑)

それにしても 私は母の言ったことは 正しかったと思いました 「子供に対する親の愛情は 他のどんな感情にも 代えがたいものであり 子供を持ってみないと わからない」 本当にそうだと思いました

私が父親になることと 失うことを 結びつけた その瞬間 私は子供たちに試されたのだと思います しかし 調査の真っ最中でなかったら 私はそのことに気づけたかどうか 分かりません 私はたくさんの 不思議な愛の形を見てきました そして私はその魅惑的なパターンに 自然と はまりこんでいきました そして どんなに救いがたい弱さにも 光は当たるのだということを見てきました

この10年間で私が目撃し学んできたのは 耐え難いほどの重責がもたらす 身のすくむような喜びです それは他の何物にも勝るということが 分かるようになりました 私はインタビューをしながら この親は 馬鹿だと思うことがありました 感謝もしない子供のために一生を捧げ 人生を棒に振り 不幸の中からアイデンティティを つむぎ出そうとするなんて しかし 私はあの日 気づいたのです 調査のおかげで私には素地ができており 他の親たちと 運命を共にする覚悟があると

ありがとうございました

(拍手)

品詞分類

- 主語

- 動詞

- 助動詞

- 準動詞

- 関係詞等

TED 日本語

TED Talks

関連動画

性別なしのトイレが必要な理由アイヴァン・カヨーティ

2016.03.18

世界のLGBTの生活とはジェニ・チャン、リサ・ダゾルス

2015.12.04

立ち向かうべきとき、聞き流すべきときアッシュ・ベッカム

2015.07.10

我が娘、妻、ロボット、そして永遠の生の追求マーティーン・ロスブラット

2015.05.18

本当の自分を隠すことの危険性モルガナ・ベイリー

2015.01.23

ゲイ・ライツ・ムーブメントが公民権運動から学んだものヨルバ・リチェン

2014.06.06

人生で最も苦しい経験から、自分らしくなるアンドリュー・ソロモン

2014.05.21

私がカミングアウトすべき理由ジーナ・ロセロ

2014.03.31

誰もが抱える心の壁―勇気を出して壁を打ち破ろうアッシュ・ベッカム

2014.02.21

「エモーショナル・コレクトネス(正しい感情表現)」を実践しようサリー・コーン

2013.12.04

「フィフティ・シェイズ・オブ・“ゲイ”」アイオ・ティレット・ライト

2013.01.30

ゲイアジェンダの神話LZ グランダーソン

2012.06.15

洋楽 おすすめ

RECOMMENDS

洋楽歌詞

ダイナマイトビーティーエス

洋楽最新ヒット2020.08.20

ディス・イズ・ミーグレイテスト・ショーマン・キャスト

洋楽人気動画2018.01.11

グッド・ライフGイージー、ケラーニ

洋楽人気動画2017.01.27

ホワット・ドゥ・ユー・ミーン?ジャスティン・ビーバー

洋楽人気動画2015.08.28

ファイト・ソングレイチェル・プラッテン

洋楽人気動画2015.05.19

ラヴ・ミー・ライク・ユー・ドゥエリー・ゴールディング

洋楽人気動画2015.01.22

アップタウン・ファンクブルーノ・マーズ、マーク・ロンソン

洋楽人気動画2014.11.20

ブレイク・フリーアリアナ・グランデ

洋楽人気動画2014.08.12

ハッピーファレル・ウィリアムス

ポップス2014.01.08

カウンティング・スターズワンリパブリック

ロック2013.05.31

ア・サウザンド・イヤーズクリスティーナ・ペリー

洋楽人気動画2011.10.26

ユー・レイズ・ミー・アップケルティック・ウーマン

洋楽人気動画2008.05.30

ルーズ・ユアセルフエミネム

洋楽人気動画2008.02.21

ドント・ノー・ホワイノラ・ジョーンズ

洋楽人気動画2008.02.15

オンリー・タイムエンヤ

洋楽人気動画2007.10.03

ミス・ア・シングエアロスミス

ロック2007.08.18

タイム・トゥ・セイ・グッバイサラ・ブライトマン

洋楽人気動画2007.06.08

シェイプ・オブ・マイ・ハートスティング

洋楽人気動画2007.03.18

ウィ・アー・ザ・ワールド(U.S.A. フォー・アフリカ)マイケル・ジャクソン

洋楽人気動画2006.05.14

ホテル・カリフォルニアイーグルス

ロック2005.07.06