TED日本語

TED Talks(英語 日本語字幕付き動画)

TED日本語 - デボラ・ゴードン: 脳や癌細胞とインターネット ― アリ達が教えてくれる事

TED Talks

脳や癌細胞とインターネット ― アリ達が教えてくれる事

What ants teach us about the brain, cancer and the Internet

デボラ・ゴードン

Deborah Gordon

内容

生態学者のデボラ・ゴードンは砂漠や熱帯地方や彼女のキッチンなど、いたる所でアリを観察しています。この魅力的なトークの中で彼女は、私達の殆んどが何も考えずに追い払っている昆虫について、彼女が取りつかれている訳を説明してくれます。彼女は、アリの生態が私達の病気やテクノロジー、人間の脳についても学ぶ事があるのだと主張します。

字幕

SCRIPT

Script

I study ants in the desert, in the tropical forest and in my kitchen, and in the hills around Silicon Valley where I live. I've recently realized that ants are using interactions differently in different environments, and that got me thinking that we could learn from this about other systems, like brains and data networks that we engineer, and even cancer.

So what all these systems have in common is that there's no central control. An ant colony consists of sterile female workers -- those are the ants you see walking around -- and then one or more reproductive females who just lay the eggs. They don't give any instructions. Even though they're called queens, they don't tell anybody what to do. So in an ant colony, there's no one in charge, and all systems like this without central control are regulated using very simple interactions. Ants interact using smell. They smell with their antennae, and they interact with their antennae, so when one ant touches another with its antennae, it can tell, for example, if the other ant is a nestmate and what task that other ant has been doing. So here you see a lot of ants moving around and interacting in a lab arena that's connected by tubes to two other arenas. So when one ant meets another, it doesn't matter which ant it meets, and they're actually not transmitting any kind of complicated signal or message. All that matters to the ant is the rate at which it meets other ants. And all of these interactions, taken together, produce a network. So this is the network of the ants that you just saw moving around in the arena, and it's this constantly shifting network that produces the behavior of the colony, like whether all the ants are hiding inside the nest, or how many are going out to forage. A brain actually works in the same way, but what's great about ants is that you can see the whole network as it happens.

There are more than 12,000 species of ants, in every conceivable environment, and they're using interactions differently to meet different environmental challenges. So one important environmental challenge that every system has to deal with is operating costs, just what it takes to run the system. And another environmental challenge is resources, finding them and collecting them. In the desert, operating costs are high because water is scarce, and the seed-eating ants that I study in the desert have to spend water to get water. So an ant outside foraging, searching for seeds in the hot sun, just loses water into the air. But the colony gets its water by metabolizing the fats out of the seeds that they eat. So in this environment, interactions are used to activate foraging. An outgoing forager doesn't go out unless it gets enough interactions with returning foragers, and what you see are the returning foragers going into the tunnel, into the nest, and meeting outgoing foragers on their way out. This makes sense for the ant colony, because the more food there is out there, the more quickly the foragers find it, the faster they come back, and the more foragers they send out. The system works to stay stopped, unless something positive happens.

So interactions function to activate foragers. And we've been studying the evolution of this system. First of all, there's variation. It turns out that colonies are different. On dry days, some colonies forage less, so colonies are different in how they manage this trade-off between spending water to search for seeds and getting water back in the form of seeds. And we're trying to understand why some colonies forage less than others by thinking about ants as neurons, using models from neuroscience. So just as a neuron adds up its stimulation from other neurons to decide whether to fire, an ant adds up its stimulation from other ants to decide whether to forage. And what we're looking for is whether there might be small differences among colonies in how many interactions each ant needs before it's willing to go out and forage, because a colony like that would forage less.

And this raises an analogous question about brains. We talk about the brain, but of course every brain is slightly different, and maybe there are some individuals or some conditions in which the electrical properties of neurons are such that they require more stimulus to fire, and that would lead to differences in brain function.

So in order to ask evolutionary questions, we need to know about reproductive success. This is a map of the study site where I have been tracking this population of harvester ant colonies for 28 years, which is about as long as a colony lives. Each symbol is a colony, and the size of the symbol is how many offspring it had, because we were able to use genetic variation to match up parent and offspring colonies, that is, to figure out which colonies were founded by a daughter queen produced by which parent colony. And this was amazing for me, after all these years, to find out, for example, that colony 154, whom I've known well for many years, is a great-grandmother. Here's her daughter colony, here's her granddaughter colony, and these are her great-granddaughter colonies. And by doing this, I was able to learn that offspring colonies resemble parent colonies in their decisions about which days are so hot that they don't forage, and the offspring of parent colonies live so far from each other that the ants never meet, so the ants of the offspring colony can't be learning this from the parent colony. And so our next step is to look for the genetic variation underlying this resemblance.

So then I was able to ask, okay, who's doing better? Over the time of the study, and especially in the past 10 years, there's been a very severe and deepening drought in the Southwestern U.S., and it turns out that the colonies that conserve water, that stay in when it's really hot outside, and thus sacrifice getting as much food as possible, are the ones more likely to have offspring colonies. So all this time, I thought that colony 154 was a loser, because on really dry days, there'd be just this trickle of foraging, while the other colonies were out foraging, getting lots of food, but in fact, colony 154 is a huge success. She's a matriarch. She's one of the rare great-grandmothers on the site. To my knowledge, this is the first time that we've been able to track the ongoing evolution of collective behavior in a natural population of animals and find out what's actually working best.

Now, the Internet uses an algorithm to regulate the flow of data that's very similar to the one that the harvester ants are using to regulate the flow of foragers. And guess what we call this analogy? The anternet is coming. (Applause) So data doesn't leave the source computer unless it gets a signal that there's enough bandwidth for it to travel on. In the early days of the Internet, when operating costs were really high and it was really important not to lose any data, then the system was set up for interactions to activate the flow of data. It's interesting that the ants are using an algorithm that's so similar to the one that we recently invented, but this is only one of a handful of ant algorithms that we know about, and ants have had 130 million years to evolve a lot of good ones, and I think it's very likely that some of the other 12,000 species are going to have interesting algorithms for data networks that we haven't even thought of yet.

So what happens when operating costs are low? Operating costs are low in the tropics, because it's very humid, and it's easy for the ants to be outside walking around. But the ants are so abundant and diverse in the tropics that there's a lot of competition. Whatever resource one species is using, another species is likely to be using that at the same time. So in this environment, interactions are used in the opposite way. The system keeps going unless something negative happens, and one species that I study makes circuits in the trees of foraging ants going from the nest to a food source and back, just round and round, unless something negative happens, like an interaction with ants of another species. So here's an example of ant security. In the middle, there's an ant plugging the nest entrance with its head in response to interactions with another species. Those are the little ones running around with their abdomens up in the air. But as soon as the threat is passed, the entrance is open again, and maybe there are situations in computer security where operating costs are low enough that we could just block access temporarily in response to an immediate threat, and then open it again, instead of trying to build a permanent firewall or fortress.

So another environmental challenge that all systems have to deal with is resources, finding and collecting them. And to do this, ants solve the problem of collective search, and this is a problem that's of great interest right now in robotics, because we've understood that, rather than sending a single, sophisticated, expensive robot out to explore another planet or to search a burning building, that instead, it may be more effective to get a group of cheaper robots exchanging only minimal information, and that's the way that ants do it. So the invasive Argentine ant makes expandable search networks. They're good at dealing with the main problem of collective search, which is the trade-off between searching very thoroughly and covering a lot of ground. And what they do is, when there are many ants in a small space, then each one can search very thoroughly because there will be another ant nearby searching over there, but when there are a few ants in a large space, then they need to stretch out their paths to cover more ground. I think they use interactions to assess density, so when they're really crowded, they meet more often, and they search more thoroughly. Different ant species must use different algorithms, because they've evolved to deal with different resources, and it could be really useful to know about this, and so we recently asked ants to solve the collective search problem in the extreme environment of microgravity in the International Space Station. When I first saw this picture, I thought, Oh no, they've mounted the habitat vertically, but then I realized that, of course, it doesn't matter. So the idea here is that the ants are working so hard to hang on to the wall or the floor or whatever you call it that they're less likely to interact, and so the relationship between how crowded they are and how often they meet would be messed up. We're still analyzing the data. I don't have the results yet. But it would be interesting to know how other species solve this problem in different environments on Earth, and so we're setting up a program to encourage kids around the world to try this experiment with different species. It's very simple. It can be done with cheap materials. And that way, we could make a global map of ant collective search algorithms. And I think it's pretty likely that the invasive species, the ones that come into our buildings, are going to be really good at this, because they're in your kitchen because they're really good at finding food and water.

So the most familiar resource for ants is a picnic, and this is a clustered resource. When there's one piece of fruit, there's likely to be another piece of fruit nearby, and the ants that specialize on clustered resources use interactions for recruitment. So when one ant meets another, or when it meets a chemical deposited on the ground by another, then it changes direction to follow in the direction of the interaction, and that's how you get the trail of ants sharing your picnic.

Now this is a place where I think we might be able to learn something from ants about cancer. I mean, first, it's obvious that we could do a lot to prevent cancer by not allowing people to spread around or sell the toxins that promote the evolution of cancer in our bodies, but I don't think the ants can help us much with this because ants never poison their own colonies. But we might be able to learn something from ants about treating cancer. There are many different kinds of cancer. Each one originates in a particular part of the body, and then some kinds of cancer will spread or metastasize to particular other tissues where they must be getting resources that they need. So if you think from the perspective of early metastatic cancer cells as they're out searching around for the resources that they need, if those resources are clustered, they're likely to use interactions for recruitment, and if we can figure out how cancer cells are recruiting, then maybe we could set traps to catch them before they become established.

So ants are using interactions in different ways in a huge variety of environments, and we could learn from this about other systems that operate without central control. Using only simple interactions, ant colonies have been performing amazing feats for more than 130 million years. We have a lot to learn from them.

Thank you.

(Applause)

私はアリを研究しています 砂漠や 熱帯林の中のアリや 我が家のキッチンや 私の住むシリコンバレー周辺の丘でも アリを調べています 最近 私は ある事に気がつきました アリ同士の「やりとり」は環境の違いで 異なった使われ方になるということです また この事から 他のシステムについて 学ぶ事があるのではと考えました 例えば 脳の仕組みや 私達が設計するデータネットワークや― 癌についてでさえもです

これら全てのシステムには 中央司令塔はないのです アリのコロニーは 生殖機能が無いメスの働きアリ ― 皆さんが歩いている所を 見かけるアリと 最低1匹の生殖を行うメスで 成り立っています このメスはひたすら卵を産むだけで 誰にも指示を与えません 「女王アリ」という名にもかかわらず― なんら命令を出すわけではありません つまり コロニーに リーダーはおらず この類の集中制御機能の無い システムは全て とても簡単な「やりとり」によって 制御されています アリ同士のやりとりには 匂いが使われます 触角でにおいを感じ取り 触角でコミュニケーションを取り合います アリ同士は触角を お互いに触れ合う事で 相手が同じ巣の仲間なのか 確認したり 相手の行動を知ることができます これは研究用アリーナです 沢山のアリが動き回り 相互に関わっています 他の2つのアリーナと チューブで つながっています アリ同士が接触する際には 相手が誰かに関わらず 複雑な信号や メッセージのやりとりは 全く行っていません アリにとって重要なのは 他のアリに出会う頻度なんです そして このような出会いを総合して ネットワークを 構成しています これが アリの出会いの 相互作用が創る アリーナの内部のネットワークです この絶えず変化するネットワークは コロニー全体の行動となって現れます 全てのアリが巣内に籠もるとか 何匹が 収穫に出るかなどを 決めているのです 実は 脳も同じように機能していますが アリの良いところは ネットワーク全体をリアルタイムで 観察出来る事です

アリはあらゆる環境下に生息し 12,000種にものぼります それぞれの異なった 環境の問題に対応する為に― 「やりとり」を様々な形で利用しています まず どのシステムもが直面する 環境上の課題は システムの維持に必要な 「運転コスト」です もう1つの環境上の 課題は「資源」です 「資源」を見つけ出し 集めるという事です 砂漠では 水が乏しい為 システム運用コストは 高くなります 私が砂漠で観察した 植物の種を食べるアリは 水を得るために 水を消費しなければなりません 巣の外で収穫活動をしているアリは 灼熱の太陽に照らされている為に 体内の水分が蒸発してしまうからです でも コロニーは種に含まれる 脂肪を代謝することにより 水を得ています このような環境下では アリ間のやりとりが 収穫行動を促進させます 収穫に向かうアリは 戻ってくるアリとの やりとりが十分でなければ 巣から出ません これは 収穫を終えたアリの隊列が 巣に戻るためにトンネルを 通過する様子ですが 収穫に向かうアリたちと 接触し合っています これは理にかなっています 沢山の餌があれば あるほど それを見つける時間が短くなるので 出たアリがすぐに戻り より沢山のアリを 送り出す仕組みになっています これは通常止まっていて 好条件下でのみ稼動するシステムです

アリ間のやりとりが 収穫活動を促進するのです 私達は このシステムの 進化についても研究しています まず コロニーによる 微妙な違いに注目しました 乾燥時に収穫活動を 減らすコロニーもあります つまり コロニーによって トレードオフの管理 つまり どれだけ 水分を消費して種を探し 見返りに種から水分を得るかの 管理に差があるのです 私たちは 収穫活動を減らす― コロニーが存在する訳を アリをニューロン(神経細胞)に見立てて 神経科学のモデルから 理解しようとしています 神経細胞が 外部からの刺激を加算して 発火するかを決めるように アリも 他のアリとの やりとりの量を加算して 収穫を行うか 決めています ですので コロニーによる 微妙な違い― それぞれのアリが 収穫に向かうのに必要な― やりとりの量に差があって それが コロニーの収穫活動の減少に つながるのかを模索しています

これは 脳に対しても 同様な疑問を投げかけます よく 脳について話をしますが もちろん それぞれの脳も微妙に違い それぞれの性質や それぞれの状況によって ニューロンの電気的特性等に 違いが生じ 発火に より多量の刺激が 必要になり その差が脳の機能の 違いに繋がるかもしれません

進化の過程を知る為には 繁殖に成功しているかどうか 知る必要があります これは私が28年間 アリ数の追跡調査を行ってきた地域の 収穫アリのコロニーの地図です この年数は コロニーの寿命とほぼ同じです 各シンボルは コロニー 大きさは 子孫の数を表しています 遺伝子の情報を利用して 親と子孫をマッチさせ どのコロニーが 2世代目女王アリによって― 設けられたのか 更には どの親コロニーの 出身なのか解明しました そして長年の調査の末 驚きの事実が判明しました 例えば この154番のコロニーは 私が 長年調査しているのですが 第一世代の 親コロニーです これが 娘のコロニーで これが 孫のコロニーです そして これらは ひ孫世代のコロニーになります この調査によって 解った事は 子孫と親コロニーは どのくらい暑ければ収穫に出ないかの 判断が似ています この子孫のコロニーは 親コロニーとは 決して出会うことの無いほど 離れているので 子孫コロニーのアリは 親コロニーから この知識を教わったはずはありません ですから 次のステップは この相似を生み出す 遺伝子の違いを探す事です

そこから どのアリが 繁栄しているかを 探ることもできます これまでの研究の中で 特にこの10年間は 南西部アメリカでは 厳しい干ばつに襲われていますが 水を節約するために 猛暑の日は 巣の中に留まり 最大限の収穫を犠牲にするコロニーが より’多くの子孫を残す事が解りました それまで 154番のコロニーは 「負け組」だと考えていました 特に乾燥した日には収穫をほとんどせず その間 他のコロニーは収穫に出て 沢山の餌を手に入れていたからです しかし 154番コロニーは 沢山の子孫を残しました 彼女は偉大な女王です この場所で稀な 3世代のコロニーを築き上げました 私の知る限り 初めてではないでしょうか 自然な動物群の集団行動が 進化する過程を追跡調査して どの行動によって いちばん繁栄するのかを 明らかにしました

インターネットは データの流れの制御に アルゴリズムを使用していますが この仕組みは 収穫アリが 餌集めに送り出す個体数を 制御する仕組みによく似ています この類似を なんと呼んでいるか ご存知ですか? 「anternet (アンターネット)」です (拍手) データの伝送路容量が 十分に確保されているという 信号を受けるまで 発信元コンピュータはデータを 送出しません インターネット初期は 運用コストは非常に高く データを紛失しない事が 極めて重要だったので システムは信号のやりとりによって データ送信を開始するように 設計されました アリが使用するアルゴリズムと 近年発明されたシステムの酷似は 興味深いものがあります しかし それは私達が知っている 一握りのアリのアルゴリズムの ほんの1つに過ぎません 一方 アリ達は1億3千万年の過程で 素晴らしいものを 数多く進化させてきました ですから 他の12,000種の アルゴリズムの中には 私達が考え付かなかった データネットワークに関しての 役立つヒントが あるに違いありません

では 運用コストが 低い場合はどうでしょう? 熱帯地方では 運用コストは下がります なぜなら 多湿の為に 巣外での作業が アリの負担にならないからです しかし 熱帯地方では アリの数が多く 種類も多く存在しますので 沢山の競争があります ある種が使っている資源は 別の種のアリも同時に 狙っているかもしれません ですので この環境では 「やりとり」は 逆の目的で使われます これは常に「オン」のシステムで 不都合がある場合のみ ストップします 私が観察したアリの1種は 木の幹や枝に収穫アリが経路を形成し 巣と餌場との往復を 何回も繰り返します 不都合が発生しない限り -- 例えば 他の種のアリと 出くわしたりしない限り やめません アリのセキュリティの1例を お見せしましょう 中央部で 1匹のアリが 自らの頭で巣の入口を塞いでいますが これは他の種に出くわした結果です 相手は 腹部を上に曲げて 動き回っているアリです 脅威が去るとすぐに 入口は 開けられます コンピュータのセキュリティでも 状況によって 運用コストが安い場合には 直面する脅威に対して 一時的に対応して 接続をブロックし 再度 接続を開始する方が 恒久的なファイアウォールや フォートレスを築くよりも 効率的かもしれません

さて もう一つの環境問題 全てのシステムにおいて 必要なのが 「資源」です 「資源」を見つけ 集める事です アリは この問題の解決に 集団探索を行っています この行為は 現在ロボット工学で 注目されている問題です なぜなら 例えばですが 他の星の探査や 火災のビルの捜索などに 洗練された高価な ロボットを1台使用するより 最小限の情報を交換する 安価なロボットを複数使った方が 効率的だと考えられていますが これは まさにアリのやり方と同じなのです 侵略的な アルゼンチンアリは 拡張可能なサーチ網を形成します このアリは 集団探索の重大な課題に 上手く対応しています 徹底的に探索するか 広い面積を探索するかの トレードオフの問題に対して このアリのやり方は 狭い面積に沢山のアリがいる場合 それぞれが 自分の周りを徹底的に探索します なぜならその周辺は他のアリが すでに探索を行っているからです しかし より大きな範囲で 数匹のアリしかいない場合は 遠くまで出向いて 捜索範囲を広げる必要があります アリ同士はやりとりから 密度を評価していると思います 非常に密な状況では 仲間に頻繁に出会うので より 徹底的な捜索を行うのです それぞれの種のアリに 様々なアルゴリズムがあるはずです なぜなら どのアリも色々な環境に 対応しながら進化してきたからです これを学ぶことは非常に役立つと考え アリに 極限の環境で 集団捜索の問題を 解いてもらうことにしました 国際宇宙ステーション内の 微小重力環境での実験です 最初に写真を見た時は 「うわっ アリの箱が垂直になっている!」 と思いましたが その後 「そうか 問題無いんだ」と 気付きました 実験の目的は アリ達は― 壁面や床面に あたる場所へ しがみつくのに必死で やりとりをする機会が減り アリの密度と アリ同士が接触する頻度の関係が めちゃくちゃになるか というものです まだ データは分析中ですので 結果は解りませんが 地球上でも 異なった環境で 様々な種の問題の解決方法を 知ることは 興味深い事です ですので 私達は 世界中の子供たちに 色々な種のアリで この実験にトライしてもらう計画を 立てています 非常に簡単で― 安価な材料で実験ができるので 世界中のアリの集団捜索に関する アルゴリズム・マップも作成出来るかもしれません 侵略的な種で建物の中に 侵入するタイプのものには 素晴らしいアルゴリズムがあるでしょう 台所にまで入って来て 食糧や水をうまく探し出すのですから

アリがよく集まってくるのが ピクニックです これは まとまった資源です 果物を見つけたら そのすぐ側にも 果物があるはずですから まとまった食糧に 特化している種のアリは 「やりとり」を 仲間の召集に使います ですから 他のアリや 地面に残された匂いに 出会った場合 アリは方向転換をして やりとりの方に向かいます このようにして ピクニックの食べ物に アリの行列がやってくるわけです

この状況から癌について 何か学べるかもしれません もちろん 癌予防のためには 私たちの体内で 癌の発生を促進する 有害物質の拡散や売買の禁止も 大切な事ですが これは アリから学ぶ事はできません アリは自らコロニーを 有害物質で汚染しませんから でも癌の治療法については 学ぶ事があるかもしれません 癌にも 沢山の種類があります それぞれの癌は体内の 決まった場所で発生し その中のいくつかは 広がって 癌細胞が必要とする 資源を得られる細胞へ転移します ですので 早期の 転移性がん細胞が 必要とする資源を 探し回っているとき まとまった資源をみつけたら 仲間を招集する やりとりをするかもしれません もし 癌細胞が仲間を集める仕組みを 解明出来れば 罠を仕掛け― 癌細胞が定着する前に 捕えられるかもしれません

アリは 様々な環境の中 様々な方法で 「やりとり」を利用しています 私達はこれらの やりとりから 他の「集中制御機能の無いシステム」― についても学ぶ事が出来ます 単純なやりとりを利用するのみで アリのコロニーは驚くべき偉業を 1億3千万年以上成し遂げてきました 私達はアリからまだまだ学ぶ事があるのです

ありがとう

(拍手)

品詞分類

- 主語

- 動詞

- 助動詞

- 準動詞

- 関係詞等

TED 日本語

TED Talks

関連動画

古代岩石が変える生命の起源説タラ・ジョキッチ

2019.10.30

40億年の進化を6分で説明 | TED Talkプロサンタ・チャクラバーティ

おすすめ 12018.07.06

深海の謎は生命への理解を変えるカレン・ロイド

2018.02.28

進化で勝ち残り、大絶滅を生き延びる方法ローレン・サラン

2017.11.21

恐竜の化石探しを通して知った、宇宙における人類ケネス・ラコバラ

2016.05.17

思わず息を呑む生後21日間のミツバチの姿アナンド・ヴァルマー

2015.05.11

スピノサウルスを発掘するまでニザール・イブラヒム

2015.04.24

自ら治療する蝶ジャープ・デ=ローデ

2015.02.09

準知的粘菌が人類に教えてくれることヘザー・バーネット

2014.07.17

ホタルの愛と偽りサラ・ルイス

2014.07.01

ヒトフェロモンのうさん臭い謎トリストラム・ワイアット

2014.05.15

自殺するコオロギ、ゾンビ化するゴキブリ、その他の寄生生物にまつわる話エド・ヨン

おすすめ 32014.03.26

ハチが消えつつある理由マーラ・スピヴァク

TED人気動画2013.09.17

絶滅種 カモノハシガエル、タスマニアン・タイガーの再生計画マイケル・アーチャー

2013.06.27

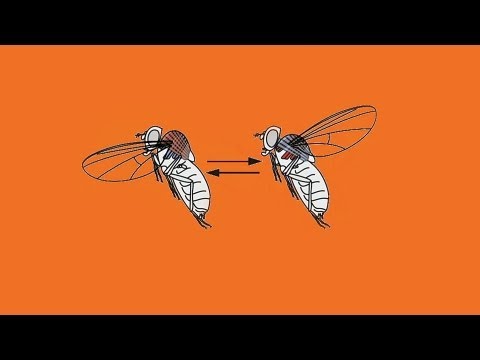

ハエはどうやって飛ぶの?マイケル・ディキンソン

2013.02.22

フンコロガシの踊りマーカス・バーン

2012.12.13

洋楽 おすすめ

RECOMMENDS

洋楽歌詞

ダイナマイトビーティーエス

洋楽最新ヒット2020.08.20

ディス・イズ・ミーグレイテスト・ショーマン・キャスト

洋楽人気動画2018.01.11

グッド・ライフGイージー、ケラーニ

洋楽人気動画2017.01.27

ホワット・ドゥ・ユー・ミーン?ジャスティン・ビーバー

洋楽人気動画2015.08.28

ファイト・ソングレイチェル・プラッテン

洋楽人気動画2015.05.19

ラヴ・ミー・ライク・ユー・ドゥエリー・ゴールディング

洋楽人気動画2015.01.22

アップタウン・ファンクブルーノ・マーズ、マーク・ロンソン

洋楽人気動画2014.11.20

ブレイク・フリーアリアナ・グランデ

洋楽人気動画2014.08.12

ハッピーファレル・ウィリアムス

ポップス2014.01.08

カウンティング・スターズワンリパブリック

ロック2013.05.31

ア・サウザンド・イヤーズクリスティーナ・ペリー

洋楽人気動画2011.10.26

ユー・レイズ・ミー・アップケルティック・ウーマン

洋楽人気動画2008.05.30

ルーズ・ユアセルフエミネム

洋楽人気動画2008.02.21

ドント・ノー・ホワイノラ・ジョーンズ

洋楽人気動画2008.02.15

オンリー・タイムエンヤ

洋楽人気動画2007.10.03

ミス・ア・シングエアロスミス

ロック2007.08.18

タイム・トゥ・セイ・グッバイサラ・ブライトマン

洋楽人気動画2007.06.08

シェイプ・オブ・マイ・ハートスティング

洋楽人気動画2007.03.18

ウィ・アー・ザ・ワールド(U.S.A. フォー・アフリカ)マイケル・ジャクソン

洋楽人気動画2006.05.14

ホテル・カリフォルニアイーグルス

ロック2005.07.06