TED日本語

TED Talks(英語 日本語字幕付き動画)

TED日本語 - チャールズ・ヘイゼルウッド: 信頼がつくるアンサンブル

TED Talks

信頼がつくるアンサンブル

Trusting the ensemble

チャールズ・ヘイゼルウッド

Charles Hazlewood

内容

指揮者チャールズ・ヘイゼルウッドが演奏のリーダーシップにおける信頼の役割について話します。それがどう機能するものなのかステージでスコットランド・アンサンブルを指揮しながら示します。またオペラ「ウ・カルメン・イ・カエリチャ」と「パラオーケストラ」の2つの音楽プロジェクトをビデオで紹介します。

字幕

SCRIPT

Script

I am a conductor, and I'm here today to talk to you about trust. My job depends upon it. There has to be, between me and the orchestra, an unshakable bond of trust, born out of mutual respect, through which we can spin a musical narrative that we all believe in.

Now in the old days, conducting, music making, was less about trust and more, frankly, about coercion. Up to and around about the Second World War, conductors were invariably dictators -- these tyrannical figures who would rehearse, not just the orchestra as a whole, but individuals within it, within an inch of their lives. But I'm happy to say now that the world has moved on, music has moved on with it. We now have a more democratic view and way of making music -- a two-way street. I, as the conductor, have to come to the rehearsal with a cast-iron sense of the outer architecture of that music, within which there is then immense personal freedom for the members of the orchestra to shine.

For myself, of course, I have to completely trust my body language. That's all I have at the point of sale. It's silent gesture. I can hardly bark out instructions while we're playing.

(Music)

Ladies and gentlemen, the Scottish Ensemble.

(Applause)

So in order for all this to work, obviously I have got to be in a position of trust. I have to trust the orchestra, and, even more crucially, I have to trust myself. Think about it: when you're in a position of not trusting, what do you do? You overcompensate. And in my game, that means you overgesticulate. You end up like some kind of rabid windmill. And the bigger your gesture gets, the more ill-defined, blurry and, frankly, useless it is to the orchestra. You become a figure of fun. There's no trust anymore, only ridicule.

And I remember at the beginning of my career, again and again, on these dismal outings with orchestras, I would be going completely insane on the podium, trying to engender a small scale crescendo really, just a little upsurge in volume. Bugger me, they wouldn't give it to me. I spent a lot of time in those early years weeping silently in dressing rooms. And how futile seemed the words of advice to me from great British veteran conductor Sir Colin Davis who said, "Conducting, Charles, is like holding a small bird in your hand. If you hold it too tightly, you crush it. If you hold it too loosely, it flies away." I have to say, in those days, I couldn't really even find the bird.

Now a fundamental and really viscerally important experience for me, in terms of music, has been my adventures in South Africa, the most dizzyingly musical country on the planet in my view, but a country which, through its musical culture, has taught me one fundamental lesson: that through music making can come deep levels of fundamental life-giving trust. Back in 2000, I had the opportunity to go to South Africa to form a new opera company. So I went out there, and I auditioned, mainly in rural township locations, right around the country. I heard about 2,000 singers and pulled together a company of 40 of the most jaw-droppingly amazing young performers, the majority of whom were black, but there were a handful of white performers.

Now it emerged early on in the first rehearsal period that one of those white performers had, in his previous incarnation, been a member of the South African police force. And in the last years of the old regime, he would routinely be detailed to go into the township to aggress the community. Now you can imagine what this knowledge did to the temperature in the room, the general atmosphere. Let's be under no illusions. In South Africa, the relationship most devoid of trust is that between a white policeman and the black community. So how do we recover from that, ladies and gentlemen? Simply through singing. We sang, we sang, we sang, and amazingly new trust grew, and indeed friendship blossomed. And that showed me such a fundamental truth, that music making and other forms of creativity can so often go to places where mere words cannot.

So we got some shows off the ground. We started touring them internationally. One of them was "Carmen." We then thought we'd make a movie of "Carmen," which we recorded and shot outside on location in the township outside Cape Town called Khayelitsha. The piece was sung entirely in Xhosa, which is a beautifully musical language, if you don't know it. It's called "U-Carmen e-Khayelitsha" -- literally "Carmen of Khayelitsha." I want to play you a tiny clip of it now for no other reason than to give you proof positive that there is nothing tiny about South African music making.

(Music)

(Applause)

Something which I find utterly enchanting about South African music making is that it's so free. South Africans just make music really freely. And I think, in no small way, that's due to one fundamental fact: they're not bound to a system of notation. They don't read music. They trust their ears. You can teach a bunch of South Africans a tune in about five seconds flat. And then, as if by magic, they will spontaneously improvise a load of harmony around that tune because they can. Now those of us that live in the West, if I can use that term, I think have a much more hidebound attitude or sense of music -- that somehow it's all about skill and systems. Therefore it's the exclusive preserve of an elite, talented body. And yet, ladies and gentlemen, every single one of us on this planet probably engages with music on a daily basis.

And if I can broaden this out for a second, I'm willing to bet that every single one of you sitting in this room would be happy to speak with acuity, with total confidence, about movies, probably about literature. But how many of you would be able to make a confident assertion about a piece of classical music? Why is this? And what I'm going to say to you now is I'm just urging you to get over this supreme lack of self-confidence, to take the plunge, to believe that you can trust your ears, you can hear some of the fundamental muscle tissue, fiber, DNA, what makes a great piece of music great. I've got a little experiment I want to try with you.

Did you know that TED is a tune? A very simple tune based on three notes -- T, E, D. Now hang on a minute. I know you're going to say to me, "T doesn't exist in music." Well ladies and gentlemen, there's a time-honored system, which composers have been using for hundreds of years, which proves actually that it does. If I sing you a musical scale: A, B, C, D, E, F, G -- and I just carry on with the next set of letters in the alphabet, same scale: H, I, J, K, L, M, N, O, P, Q, R, S, T -- there you go. T, see it's the same as F in music. So T is F. So T, E, D is the same as F, E, D. Now that piece of music that we played at the start of this session had enshrined in its heart the theme, which is TED. Have a listen.

(Music)

Do you hear it? Or do I smell some doubt in the room? Okay, we'll play it for you again now, and we're going to highlight, we're going to poke out the T, E, D. If you'll pardon the expression.

(Music)

Oh my goodness me, there it was loud and clear, surely. I think we should make this even more explicit. Ladies and gentlemen, it's nearly time for tea. Would you reckon you need to sing for your tea, I think? I think we need to sing for our tea. We're going to sing those three wonderful notes: T, E, D. Will you have a go for me?

Audience: T, E, D.

Charles Hazlewood: Yeah, you sound a bit more like cows really than human beings. Shall we try that one again? And look, if you're adventurous, you go up the octave. T, E, D.

Audience: T, E, D.

CH: Once more with vim. (Audience: T, E, D.)

There I am like a bloody windmill again, you see. Now we're going to put that in the context of the music. The music will start, and then at a signal from me, you will sing that. (Music) One more time, with feeling, ladies and gentlemen. You won't make the key otherwise. Well done, ladies and gentlemen. It wasn't a bad debut for the TED choir, not a bad debut at all.

Now there's a project that I'm initiating at the moment that I'm very excited about and wanted to share with you, because it is all about changing perceptions, and, indeed, building a new level of trust. The youngest of my children was born with cerebral palsy, which as you can imagine, if you don't have an experience of it yourself, is quite a big thing to take on board. But the gift that my gorgeous daughter has given me, aside from her very existence, is that it's opened my eyes to a whole stretch of the community that was hitherto hidden, the community of disabled people. And I found myself looking at the Paralympics and thinking how incredible how technology's been harnessed to prove beyond doubt that disability is no barrier to the highest levels of sporting achievement. Of course there's a grimmer side to that truth, which is that it's actually taken decades for the world at large to come to a position of trust, to really believe that disability and sports can go together in a convincing and interesting fashion.

So I find myself asking: where is music in all of this? You can't tell me that there aren't millions of disabled people, in the U.K. alone, with massive musical potential. So I decided to create a platform for that potential. It's going to be Britain's first ever national disabled orchestra. It's called Paraorchestra.

I'm going to show you a clip now of the very first improvisation session that we had. It was a really extraordinary moment. Just me and four astonishingly gifted disabled musicians. Normally when you improvise -- and I do it all the time around the world -- there's this initial period of horror, like everyone's too frightened to throw the hat into the ring, an awful pregnant silence. Then suddenly, as if by magic, bang! We're all in there and it's complete bedlam. You can't hear anything. No one's listening. No one's trusting. No one's responding to each other. Now in this room with these four disabled musicians, within five minutes a rapt listening, a rapt response and some really insanely beautiful music.

(Video) (Music)

Nicholas:: My name's Nicholas McCarthy. I'm 22, and I'm a left-handed pianist. And I was born without my left hand -- right hand. Can I do that one again?

(Music)

Lyn: When I'm making music, I feel like a pilot in the cockpit flying an airplane. I become alive.

(Music)

Clarence: I would rather be able to play an instrument again than walk. There's so much joy and things I could get from playing an instrument and performing. It's removed some of my paralysis.

(Music)

(Applause)

CH: I only wish that some of those musicians were here with us today, so you could see at firsthand how utterly extraordinary they are. Paraorchestra is the name of that project. If any of you thinks you want to help me in any way to achieve what is a fairly impossible and implausible dream still at this point, please let me know. Now my parting shot comes courtesy of the great Joseph Haydn, wonderful Austrian composer in the second half of the 18th century -- spent the bulk of his life in the employ of Prince Nikolaus Esterhazy, along with his orchestra. Now this prince loved his music, but he also loved the country castle that he tended to reside in most of the time, which is just on the Austro-Hungarian border, a place called Esterhazy -- a long way from the big city of Vienna.

Now one day in 1772, the prince decreed that the musicians' families, the orchestral musicians' families, were no longer welcome in the castle. They weren't allowed to stay there anymore; they had to be returned to Vienna -- as I say, an unfeasibly long way away in those days. You can imagine, the musicians were disconsolate. Haydn remonstrated with the prince, but to no avail. So given the prince loved his music, Haydn thought he'd write a symphony to make the point.

And we're going to play just the very tail end of this symphony now. And you'll see the orchestra in a kind of sullen revolt. I'm pleased to say, the prince did take the tip from the orchestral performance, and the musicians were reunited with their families. But I think it sums up my talk rather well, this, that where there is trust, there is music -- by extension life. Where there is no trust, the music quite simply withers away.

(Music)

(Applause)

私は指揮者ですが 今日は皆さんに 信頼についてお話しします これは 私の仕事が基礎とするものです 指揮者とオーケストラの間には 揺るぎない絆が必要であり それは互いへの尊敬から生まれるものです それを通して私たちが信じるところの 音楽の物語を紡ぎ出すのです

昔は指揮というと 信頼というよりも 率直なところ強制でさせるものでした 第二次世界大戦以前の指揮者というと みんな独裁者でした 専制君主のような存在で オーケストラ全体ばかりでなく 個々のメンバーの生活の細部まで指図していました 幸い世界は進歩して その中で音楽も進歩しました 今ではもっと民主的な見方と方法がとられており もはや一方通行ではありません 私は指揮者として 音楽のしっかりした外枠を用意する必要がありますが その中には大きな自由があって オーケストラのメンバーを輝かせるのです

私はまた 自分のボディランゲージを強く信頼する必要があります それが私に使えるすべてだからです 無言の身振りです 演奏中に大声で指示するわけにはいきません

(演奏)

ご紹介します スコットランド・アンサンブルです

(拍手)

この全体を機能させるには 信頼を築く必要があります オーケストラへの信頼が必要であり さらに重要なのは 自分自身への信頼です 考えてください 信頼がなかったら何ができるでしょう? 埋め合わせようと オーバーなジェスチャーをし 狂った風車みたいになることでしょう ジェスチャーが大きくなるほど 不明瞭であいまいになり オーケストラの役には立ちません 滑稽なだけです 信頼は消え 嘲りだけが残るでしょう

指揮を始めた頃のことをよく覚えています 惨めなオーケストラ公演の繰り返しで 私が指揮台の上でムキになって ちょっとしたクレッシェンドを ― ほんの小さな高まりを作ろうとしても オーケストラは応えてくれません 始めの頃はよく控え室で 長いこと静かに泣いていたものです イギリスのベテラン指揮者コリン・デイヴィスのアドバイスも 無意味に思えました 「指揮というのはね チャールズ 小鳥をつかむようなものなんだ 握るのが強すぎたら小鳥を潰してしまう 握るのが緩すぎたら逃げてしまう」 当時の私にはその鳥を見つけることさえできない気がしました

私にとって 音楽における根本的で本質的に重要な経験となったのは 南アフリカでの冒険でした 地上でこれほどめくるめく音楽的な国はちょっとないでしょう その音楽文化を通して 1つ極めて根本的な教訓を教えてくれました ともに音楽をやる中で 根源的な深いレベルの 生きた信頼を生み出すことでができるということです 2000年に南アフリカで新しい歌劇団の結成に 取り組む機会がありました 現地に赴き 主に国内あちこちの 非白人居住区でオーディションをしました 2,000人の歌手の歌を聴き 驚くばかりの才能に溢れた 若い歌手40人からなる歌劇団を作りました 大半は黒人でしたが 白人の歌手も何人かいました

最初のリハーサルのとき 白人歌手の一人が 以前 南アフリカ警官隊の 一員だったことがわかりました 旧体制の終わりの時期には 非白人居住区の人々への攻撃に たびたび派遣されていました この情報がその場の空気に及ぼした影響は 想像に難くないでしょう 現実に目を向けましょう 南アフリカで何よりも信頼がないのは 白人警官と 黒人コミュニティの間です どうやってそこから立ち直ったと思いますか? 歌を通してです 私たちは ただひたすら 歌い続けました すると驚くことに信頼が芽生え 友情が花開いたのです それは深い真実に気づかせてくれました 音楽やその他の創造的活動というのは 時に言葉では辿り着けない場所へと 連れて行ってくれるのです

私たちは公演や海外ツアーをするようになり 演目の1つは「カルメン」でしたが その映画を作ろうという話になって ケープタウン郊外のカエリチャという 非白人居住区で収録と撮影をしました 曲は全部コーサ語で歌われています 美しい音楽的な言葉です タイトルは「ウ・カルメン・イ・カエリチャ」 「カエリチャのカルメン」という意味です 南アフリカの音楽が どれほどのものか示す証拠として 映画の一部をご覧いただきたいと思います

(音楽)

(拍手)

南アフリカの音楽表現で 私がすっかり魅了されたのは その自由さです 彼らは本当に自由に音楽を生み出すのです その少なからぬ部分は 彼らが表記法に囚われないという 根本的な事実によるのだと思います 彼らは楽譜を読みません 自分の耳を信頼しているのです たくさんの南アフリカ人相手に旋律を5秒で教えられ 彼らは魔法のように その旋律をベースにたくさんのハーモニーを即興で作り出します 単にそうできるのです 西洋に住む我々の音楽に対する態度や感覚は ずっと融通が利かないものです スキルとシステムがすべてです 一部のエリート 才能ある人間だけのものです それでもこの地球上の誰もが 日々音楽に関わっているのです

もっと一般的なところでは ここにいる誰もがまったくの自信を持って 映画や文学について 嬉々として話すことでしょうが クラシック音楽の曲となると 自信を持って語れる人が どれほどいるでしょう? なぜそうなのでしょう? 私が言いたいのは その極度の自信のなさを克服し 飛躍して欲しいということです 自分の耳を信頼し 名曲を名曲たらしめている 基本的な筋組織 神経 DNAを 聞き取れるのだと信じてほしいのです それでひとつ実験をしたいと思います

TEDが旋律を表しているのは ご存じでしたか? 3つの音からなるシンプルな調べです T E D ちょっと待ってください 「Tなんて音はない」と言いたいのはわかります 実は作曲家たちが何百年も使ってきた 伝統的な表記法では Tという音は確かにあるのです 音階をA B C D E F G と歌った後 アルファベットの続きにそのまま進むのです H I J K L M N O P Q R S T ほら これは通常のFと同じです TはFなのです だからT E DはF E Dになります 講演のはじめに演奏した 曲の主題の中には TEDが埋め込まれていました お聞きください

(演奏)

わかりましたか? なんか疑いの空気が漂っていますね もう一度やりましょう TEDが際立って突き出すようにやりましょう お下品でごめんなさい

(演奏)

大きな音ではっきり聞こえましたね もっとはっきりさせましょう 皆さん もうすぐお茶の時間です お茶をいただくには歌わなくちゃいけません お茶のためにみんなで歌いましょう この素晴らしい3つの音 TEDを歌うんです やってもらえますか?

(聴衆) T E D

人よりは牛の声みたいでしたね もう一度やりましょうか 思い切ってオクターブ上げて T E D

(聴衆) T E D

もう一度元気よく (聴衆: T E D)

また狂った風車に戻った感じです 今度は音楽のコンテキストの中でやってみましょう 演奏が始まったら 私の合図で皆さん歌ってください (演奏) もう一度 気持ちを込めて そうしないとお茶はなしですよ 皆さん大変よくできました TED合唱団のデビューとしては 悪くありません

今立ち上げようとしているプロジェクトで 夢中になっているものがあるのでご紹介したい これはみんなの認識を変え 新たなレベルの信頼を作り出すものです 私の末の子は生まれながらの脳性麻痺で それを受け入れるのがいかに大きなことかは 自分で経験しなければ 分からないと思います 私の素晴らしい娘が私に与えてくれた贈り物が何かというと その子の存在そのものを別にすると これまで見えていなかった 身障者コミュニティの広がりに 私の目を見開かせてくれたことです パラリンピックを見たとき 最高レベルの運動能力を達成するのに 身体障害は壁にならないと示す上で テクノロジーがいかに有用か感心しました もっともこの事実には厳しい側面もあり 身障者とスポーツは 面白く訴求力あるものとして 結びつきうるということを 世界の多くの人が理解し信頼するようになるには 何十年もかかったのです

それで自問しました その点音楽はどうなんだろう? イギリスに限っても 優れた音楽の潜在能力を持つ身障者が 何百万といることでしょう だからその能力を育む基盤を作ることにしました これはイギリス初の 身障者のための国立オーケストラで 「パラオーケストラ」という名前です

最初に即興セッションをしたときの ビデオをご覧いただきます 本当にものすごい体験でした 驚くほどの才能を持つ4人の障害者演奏家と私だけでやりました 即興をするときは通常 私は世界中でやっていますが はじめに緊迫した時間帯があって みんな始めるのを怖れ 腹を探り合うような重い沈黙があるのですが それから突然魔法のようにはじけ 大騒ぎのようになって 何も聞こえず 誰も聞かず 信頼などどこにもなく 音楽的な受け応えもないのです それがこの4人の身障者演奏家の場合 5分もせずに うっとりと聞き うっとりと応じ そして並外れて美しい音楽を奏でたのです

(ビデオ)

(ニコラス) 僕はニコラス・マッカーシー 22歳の 左利きピアニストです 左手を持たずに生まれてきました・・・というか右手を もう一度お願いできますか?

(演奏)

(リン) 音楽を作っていると 飛行機を操縦しているパイロットのような気分になります 生きているんだと

(演奏)

(クラレンス) 歩けるようになるよりも 楽器をまた演奏できるようになりたい 楽器を弾き パフォーマンスすることで得られる喜びはとても大きく 麻痺の一部を取り除きさえしてくれた

(演奏)

(拍手)

あの音楽家の中の誰かがこの場にいてくれたらと思います 彼らがどれほど素晴らしいか直接見ることができたでしょう パラオーケストラがこのプロジェクトの名前です 今はまだ信じがたく不可能に思える この夢の実現のために どんな形であれ手を貸してくださる方は どうか知らせてください 最後に 偉大なヨーゼフ・ハイドンの話をしましょう 18世紀後半オーストリアのすばらしい作曲家で 生涯の大半を 楽団とともにニコラウス・エステルハージに仕えました エステルハージ公は音楽好きでしたが 片田舎の城が 気に入っていて 多くの時をそこで過ごしていました オーストリア=ハンガリー帝国の 国境に近い エステルハージという 大都会ウィーンからは遠く隔たった場所です

1772年のある日 エステルハージ公は 楽団員の家族を 今後城に受け入れないという 布告を出しました 城にいられなくなり ウィーンに帰らなければなりません 当時は滅多に行き来できないような遠隔地です 音楽家たちがいかに悲嘆に暮れたか想像に難くないでしょう ハイドンがエステルハージ公に諫言しても聞き入れられません エステルハージ公は音楽好きだったので ハイドンは交響曲で気持ちを伝えることにしました

その曲の最後の部分をこれからお聴かせします オーケストラが一種の反抗を示すのがわかるでしょう 幸いエステルハージ公は その演奏の心を察し 音楽家たちは再び 家族と暮らせるようになりました これは私の話の要点をよく示していると思います 信頼ある所に 音楽は生き続け 信頼ない所で 音楽はしおれてしまうのです

(演奏)

(拍手)

品詞分類

- 主語

- 動詞

- 助動詞

- 準動詞

- 関係詞等

TED 日本語

TED Talks

関連動画

素晴らしいアイデアの見つけ方OK Go

2017.06.16

しびれるようなアコースティック・ギターの演奏ロドリーゴ・イ・ガブリエーラ

2017.03.09

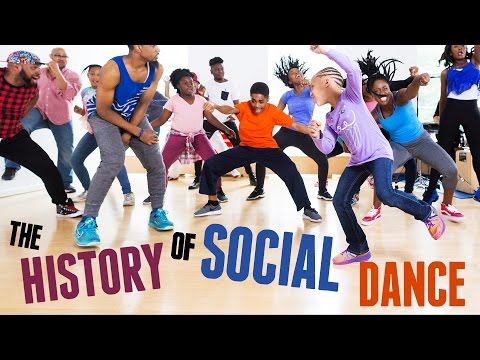

25のムーブから見る、アメリカの大衆ダンスの歴史カミーユ・A・ブラウン

2016.10.20

『リデンプション・ソング(あがないの歌)』ジョン・レジェンド

2016.08.10

音楽の力で光と色の世界へカーキ・キング

2015.12.03

11歳の神童が奏でるモダンジャズピアノジョーイ・アレキサンダー

2015.06.19

一人5役の女性による、セックスについての未来の授業サラ・ジョーンズ

2015.06.09

終身刑に服する女性たちの感動の歌声ザ・レディー・ライファーズ

2015.05.15

私のヒーロー、ハリケーンに向かってボートを漕いだ女性に贈る歌ドーン・ランデス

2015.05.08

ダンサー、シンガー、チェリストによる、目を見張るような創造の瞬間ビル・T・ジョーンズ

2015.05.06

マジックでたどる「偶然」を探す旅ヘルダー・ギマレス

2015.02.27

渦巻く紙と風と光の中のダンスアカシュ・オデドラ

2014.12.05

なぜピアノを路上や空中に持ち出すのかダリア・ファン・ベルケン

2014.10.03

どうか皆さんお願いします “awesome”に本来のawe(畏敬)の意味を取り戻しましょうジル・シャーガー

2014.08.29

あなたは人間ですか?ゼイ・フランク

2014.07.18

2つのマニアックなこだわりが出会うところ ― それはマジックデヴィッド・クォン

2014.07.11

洋楽 おすすめ

RECOMMENDS

洋楽歌詞

ダイナマイトビーティーエス

洋楽最新ヒット2020.08.20

ディス・イズ・ミーグレイテスト・ショーマン・キャスト

洋楽人気動画2018.01.11

グッド・ライフGイージー、ケラーニ

洋楽人気動画2017.01.27

ホワット・ドゥ・ユー・ミーン?ジャスティン・ビーバー

洋楽人気動画2015.08.28

ファイト・ソングレイチェル・プラッテン

洋楽人気動画2015.05.19

ラヴ・ミー・ライク・ユー・ドゥエリー・ゴールディング

洋楽人気動画2015.01.22

アップタウン・ファンクブルーノ・マーズ、マーク・ロンソン

洋楽人気動画2014.11.20

ブレイク・フリーアリアナ・グランデ

洋楽人気動画2014.08.12

ハッピーファレル・ウィリアムス

ポップス2014.01.08

カウンティング・スターズワンリパブリック

ロック2013.05.31

ア・サウザンド・イヤーズクリスティーナ・ペリー

洋楽人気動画2011.10.26

ユー・レイズ・ミー・アップケルティック・ウーマン

洋楽人気動画2008.05.30

ルーズ・ユアセルフエミネム

洋楽人気動画2008.02.21

ドント・ノー・ホワイノラ・ジョーンズ

洋楽人気動画2008.02.15

オンリー・タイムエンヤ

洋楽人気動画2007.10.03

ミス・ア・シングエアロスミス

ロック2007.08.18

タイム・トゥ・セイ・グッバイサラ・ブライトマン

洋楽人気動画2007.06.08

シェイプ・オブ・マイ・ハートスティング

洋楽人気動画2007.03.18

ウィ・アー・ザ・ワールド(U.S.A. フォー・アフリカ)マイケル・ジャクソン

洋楽人気動画2006.05.14

ホテル・カリフォルニアイーグルス

ロック2005.07.06