TED日本語

TED Talks(英語 日本語字幕付き動画)

TED日本語 - ローラ・ロビンソン: 神秘的な海底で私が出会う秘密

TED Talks

神秘的な海底で私が出会う秘密

The secrets I find on the mysterious ocean floor

ローラ・ロビンソン

Laura Robinson

内容

海面下数百メートルで、ローラ・ロビンソンは巨大な海山の急斜面を徹底的に調査しています。長い時を経て海がどのように変化したのかを突き止めるため、千年の時を経たサンゴの化石を探し求め、原子炉で分析するのです。彼女は地球の歴史の研究から地球の未来はどうなるのか、手がかりを得ようとしています。

字幕

SCRIPT

Script

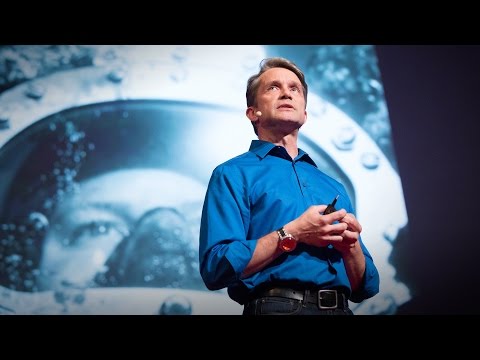

Well, I'm an ocean chemist. I look at the chemistry of the ocean today. I look at the chemistry of the ocean in the past. The way I look back in the past is by using the fossilized remains of deepwater corals. You can see an image of one of these corals behind me. It was collected from close to Antarctica, thousands of meters below the sea, so, very different than the kinds of corals you may have been lucky enough to see if you've had a tropical holiday.

So I'm hoping that this talk will give you a four-dimensional view of the ocean. Two dimensions, such as this beautiful two-dimensional image of the sea surface temperature. This was taken using satellite, so it's got tremendous spatial resolution. The overall features are extremely easy to understand. The equatorial regions are warm because there's more sunlight. The polar regions are cold because there's less sunlight. And that allows big icecaps to build up on Antarctica and up in the Northern Hemisphere. If you plunge deep into the sea, or even put your toes in the sea, you know it gets colder as you go down, and that's mostly because the deep waters that fill the abyss of the ocean come from the cold polar regions where the waters are dense.

If we travel back in time 20,000 years ago, the earth looked very much different. And I've just given you a cartoon version of one of the major differences you would have seen if you went back that long. The icecaps were much bigger. They covered lots of the continent, and they extended out over the ocean. Sea level was 120 meters lower. Carbon dioxide [ levels ] were very much lower than they are today. So the earth was probably about three to five degrees colder overall, and much, much colder in the polar regions.

What I'm trying to understand, and what other colleagues of mine are trying to understand, is how we moved from that cold climate condition to the warm climate condition that we enjoy today. We know from ice core research that the transition from these cold conditions to warm conditions wasn't smooth, as you might predict from the slow increase in solar radiation. And we know this from ice cores, because if you drill down into ice, you find annual bands of ice, and you can see this in the iceberg. You can see those blue-white layers. Gases are trapped in the ice cores, so we can measure CO2 -- that's why we know CO2 was lower in the past -- and the chemistry of the ice also tells us about temperature in the polar regions. And if you move in time from 20,000 years ago to the modern day, you see that temperature increased. It didn't increase smoothly. Sometimes it increased very rapidly, then there was a plateau, then it increased rapidly. It was different in the two polar regions, and CO2 also increased in jumps.

So we're pretty sure the ocean has a lot to do with this. The ocean stores huge amounts of carbon, about 60 times more than is in the atmosphere. It also acts to transport heat across the equator, and the ocean is full of nutrients and it controls primary productivity.

So if we want to find out what's going on down in the deep sea, we really need to get down there, see what's there and start to explore. This is some spectacular footage coming from a seamount about a kilometer deep in international waters in the equatorial Atlantic, far from land. You're amongst the first people to see this bit of the seafloor, along with my research team. You're probably seeing new species. We don't know. You'd have to collect the samples and do some very intense taxonomy. You can see beautiful bubblegum corals. There are brittle stars growing on these corals. Those are things that look like tentacles coming out of corals. There are corals made of different forms of calcium carbonate growing off the basalt of this massive undersea mountain, and the dark sort of stuff, those are fossilized corals, and we're going to talk a little more about those as we travel back in time.

To do that, we need to charter a research boat. This is the James Cook, an ocean-class research vessel moored up in Tenerife. Looks beautiful, right? Great, if you're not a great mariner. Sometimes it looks a little more like this. This is us trying to make sure that we don't lose precious samples. Everyone's scurrying around, and I get terribly seasick, so it's not always a lot of fun, but overall it is.

So we've got to become a really good mapper to do this. You don't see that kind of spectacular coral abundance everywhere. It is global and it is deep, but we need to really find the right places. We just saw a global map, and overlaid was our cruise passage from last year. This was a seven-week cruise, and this is us, having made our own maps of about 75,000 square kilometers of the seafloor in seven weeks, but that's only a tiny fraction of the seafloor. We're traveling from west to east, over part of the ocean that would look featureless on a big-scale map, but actually some of these mountains are as big as Everest. So with the maps that we make on board, we get about 100-meter resolution, enough to pick out areas to deploy our equipment, but not enough to see very much. To do that, we need to fly remotely-operated vehicles about five meters off the seafloor. And if we do that, we can get maps that are one-meter resolution down thousands of meters. Here is a remotely-operated vehicle, a research-grade vehicle. You can see an array of big lights on the top. There are high-definition cameras, manipulator arms, and lots of little boxes and things to put your samples.

Here we are on our first dive of this particular cruise, plunging down into the ocean. We go pretty fast to make sure the remotely operated vehicles are not affected by any other ships. And we go down, and these are the kinds of things you see. These are deep sea sponges, meter scale. This is a swimming holothurian -- it's a small sea slug, basically. This is slowed down. Most of the footage I'm showing you is speeded up, because all of this takes a lot of time. This is a beautiful holothurian as well. And this animal you're going to see coming up was a big surprise. I've never seen anything like this and it took us all a bit surprised. This was after about 15 hours of work and we were all a bit trigger-happy, and suddenly this giant sea monster started rolling past. It's called a pyrosome or colonial tunicate, if you like. This wasn't what we were looking for. We were looking for corals, deep sea corals. You're going to see a picture of one in a moment. It's small, about five centimeters high. It's made of calcium carbonate, so you can see its tentacles there, moving in the ocean currents. An organism like this probably lives for about a hundred years. And as it grows, it takes in chemicals from the ocean. And the chemicals, or the amount of chemicals, depends on the temperature; it depends on the pH, it depends on the nutrients. And if we can understand how these chemicals get into the skeleton, we can then go back, collect fossil specimens, and reconstruct what the ocean used to look like in the past. And here you can see us collecting that coral with a vacuum system, and we put it into a sampling container. We can do this very carefully, I should add.

Some of these organisms live even longer. This is a black coral called Leiopathes, an image taken by my colleague, Brendan Roark, about 500 meters below Hawaii. Four thousand years is a long time. If you take a branch from one of these corals and polish it up, this is about 100 microns across. And Brendan took some analyses across this coral -- you can see the marks -- and he's been able to show that these are actual annual bands, so even at 500 meters deep in the ocean, corals can record seasonal changes, which is pretty spectacular.

But 4,000 years is not enough to get us back to our last glacial maximum. So what do we do? We go in for these fossil specimens. This is what makes me really unpopular with my research team. So going along, there's giant sharks everywhere, there are pyrosomes, there are swimming holothurians, there's giant sponges, but I make everyone go down to these dead fossil areas and spend ages kind of shoveling around on the seafloor. And we pick up all these corals, bring them back, we sort them out. But each one of these is a different age, and if we can find out how old they are and then we can measure those chemical signals, this helps us to find out what's been going on in the ocean in the past.

So on the left-hand image here, I've taken a slice through a coral, polished it very carefully and taken an optical image. On the right-hand side, we've taken that same piece of coral, put it in a nuclear reactor, induced fission, and every time there's some decay, you can see that marked out in the coral, so we can see the uranium distribution. Why are we doing this? Uranium is a very poorly regarded element, but I love it. The decay helps us find out about the rates and dates of what's going on in the ocean. And if you remember from the beginning, that's what we want to get at when we're thinking about climate. So we use a laser to analyze uranium and one of its daughter products, thorium, in these corals, and that tells us exactly how old the fossils are.

This beautiful animation of the Southern Ocean I'm just going to use illustrate how we're using these corals to get at some of the ancient ocean feedbacks. You can see the density of the surface water in this animation by Ryan Abernathey. It's just one year of data, but you can see how dynamic the Southern Ocean is. The intense mixing, particularly the Drake Passage, which is shown by the box, is really one of the strongest currents in the world coming through here, flowing from west to east. It's very turbulently mixed, because it's moving over those great big undersea mountains, and this allows CO2 and heat to exchange with the atmosphere in and out. And essentially, the oceans are breathing through the Southern Ocean. We've collected corals from back and forth across this Antarctic passage, and we've found quite a surprising thing from my uranium dating: the corals migrated from south to north during this transition from the glacial to the interglacial. We don't really know why, but we think it's something to do with the food source and maybe the oxygen in the water.

So here we are. I'm going to illustrate what I think we've found about climate from those corals in the Southern Ocean. We went up and down sea mountains. We collected little fossil corals. This is my illustration of that. We think back in the glacial, from the analysis we've made in the corals, that the deep part of the Southern Ocean was very rich in carbon, and there was a low-density layer sitting on top. That stops carbon dioxide coming out of the ocean. We then found corals that are of an intermediate age, and they show us that the ocean mixed partway through that climate transition. That allows carbon to come out of the deep ocean. And then if we analyze corals closer to the modern day, or indeed if we go down there today anyway and measure the chemistry of the corals, we see that we move to a position where carbon can exchange in and out. So this is the way we can use fossil corals to help us learn about the environment.

So I want to leave you with this last slide. It's just a still taken out of that first piece of footage that I showed you. This is a spectacular coral garden. We didn't even expect to find things this beautiful. It's thousands of meters deep. There are new species. It's just a beautiful place. There are fossils in amongst, and now I've trained you to appreciate the fossil corals that are down there.

So next time you're lucky enough to fly over the ocean or sail over the ocean, just think -- there are massive sea mountains down there that nobody's ever seen before, and there are beautiful corals.

Thank you.

(Applause)

私は海洋化学者です 現在の海洋の化学を調査し 過去の海洋の化学を考察します 過去の考察には 深海にある サンゴの化石を使います これはサンゴの写真です 南極付近の水深数千メートルの 深海で採取されたもので 南国に行ったことがあれば 運良く見ることもある サンゴとはかなり違います

この話で海洋の4次元的な見方を 示したいと思います 例えばこの美しい 海面水温の平面画像は 2次元になります これは驚異的な空間解像度を備えた 人工衛星で撮影されました 全体的な特徴は 実にわかりやすいものです 赤道地域は 日射量が多いため温暖で 極地は日射量が少ないため 寒冷です これにより南極大陸と北極圏で 氷冠が発達します もし皆さんが海に深く飛び込むか つま先を入れるだけでも 深くなるにつれて 冷たくなるのが分かります その主な理由は 深海に広がる底層水は 極地の冷たい高密度水が 循環したものだからです

2万年前にさかのぼると 地球は今と随分違って見えます 大昔に時間を巻き戻すと 目にするであろう 主な違いの一つをご覧に入れます 氷冠はずっと広大でした 氷の塊が多くの大陸を覆い 海上まで広がっていました 海面は今より120メートル低く 二酸化炭素の量は 今よりずっと低レベルでした 故に当時の地球の気温は 全体的に3~5度低く 極地の気温は 更にずっと低かったと考えられます

私と同僚たちが 理解に努めているのは どのようにして 昔の寒冷な気候から 現在の温暖な気候へと 移り変わったのかです 氷床コアの研究から 寒冷期から温暖期への移行は 太陽放射量の緩やかな増加をもとに 皆さんが予想するほど 安定的ではなかったことが分かります 氷床コアからこれらが分かるのは 氷を下に掘り進めて行くと 年毎の層が見られるからです 氷山にもあります このような青と白の層です 氷床コアにはガスが閉じ込められており 二酸化炭素濃度の測定が可能で 昔は二酸化炭素濃度が 低かったと知ることができます また 氷の化学的性質から 極地の気温の情報も得られます 皆さんがもしも 2万年前から現代に来れば 気温の上昇に気付きます 気温の上昇は不安定でした 急激に上昇することもあれば 停滞期に入ったり また急上昇したりしました これは南北の極地で異なり 二酸化炭素濃度も急上昇しました

私たちは海との大きな関連を 確信しています 海は大量の炭素を貯えていて その量は大気中の約60倍です それは同じく赤道を越えて 熱を運ぶように作用し 海は栄養豊富で これが基礎生産力を左右します

深海で何が起きているかを 知るには 実際に深海に潜り 何があるかを見て 調査することが不可欠です この見事な映像は 陸地から遠く離れた 大西洋赤道域の国際水域にある 水深約1キロの海山で撮影しました 我々研究チームを含めて このような海底の映像を見たことある人は ほとんどいません 皆さんはおそらく私たちも知らない 新種の生物を見ています サンプルを収集し 一心不乱に分類するだけです バブルガムサンゴがいます サンゴに潜んで成長する クモヒトデもいます サンゴから伸びている 触手のようなものです 様々な形態の 炭酸カルシウムから成るサンゴが 巨大な海山の玄武岩の上に 成長しています この黒っぽい物体は 化石化したサンゴです 後で昔の話をするので これについてもう少し説明します

まず私たちは調査用ボートを借ります テネリフェ島に停泊する海洋調査船 ジェームズ・クック号です 美しいですね 船乗りでなくても分かります このようにしていることもあります 貴重なサンプルを失くしていないか 確認している場面です 皆が忙しく動き回ったり 私はひどい船酔いをしたりと 楽しいことばかりではありませんが 大抵は楽しいです

私たちは腕利きの 地図製作者になる必要がありました このように見事なサンゴの分布は なかなかありません 世界中の深海にありますが 私たちは本当に適当な 場所を見つける必要があります 今見たのが世界の海底地図 その上に重ねたのが 昨年の航路です 7週間の航海でした 約7万5千平方キロに及ぶ ― 海底の地図をたった7週間で 独自に作成しましたが これは海底のほんの一部分です 西から東へ移動します 大きな縮尺の地図では 海底は何の特徴もなく見えますが これらの山のいくつかは エベレスト級の大きさです 私たちが船上で作成する地図では 約100メートルの解像度が得られ これは機材の配置場所を選ぶには 十分ですが 観察には不十分です このため遠隔操作の無人探査機を 海底から約5メートルで 泳がせる必要があります すると水深数千メートル地点で 1メートルの解像度の地図が得られます この遠隔操作無人探査機は 研究用のレベルです 上部にずらりと並んだ 大きなライトが見えます 高解像度カメラや マニピュレーターアーム サンプルを収めるための 多数の小箱などがあります

さあ 今回の航海で初の潜水です 海に潜っています 無人探査機が他の船の影響を 受けないように かなりの高速で潜らせます さらに深く潜ると このような物が見えます 体長1メートルほどの 海綿動物がいます これは泳ぐ棘皮動物 つまり小さなナマコです これはスローモーションです 映像の大部分は 実際は長時間かかるので 早送りしています これもまた 美しいナマコです これからお見せする動物に 皆さん驚くでしょう 私も見たことがなかったので 一同が驚いたものです 約15時間の作業の後で 私たちが少しイライラしてきた頃 突如この巨大な海の怪物が くねりながら通ったのです これはパイロソーマもしくは 群体ホヤと呼ばれています 私たちが探していた物では ありませんでした 私たちが探していたのは 深海のサンゴです ある映像をお見せします 小形で体長は5センチ程です 炭酸カルシウムでできているので 触手が見えます 海流を受けて動いています このような生物は 恐らく100年は生きています そして成長しながら 海から化学物質を取り込みます その化学物質の種類や量は 水温、pH値や栄養素によって 異なります どのように化学物質が 骨格に取り込まれるかが分かれば 戻って化石標本を収集し 昔の海がどういうありさまだったのか 再現できます これは私たちが 真空装置でサンゴを収集し サンプル容器に入れている様子です これはとても慎重な作業だと 言っておきます

中にはさらに長命な生物もいます これはクロサンゴ類のレイオパテスで 同僚のブレンダン・ロアークが ハワイの海面下約500メートルで 撮影しました 4000年は経過しています この枝を1本採って磨いてみると 画面のさしわたしが数百ミクロンです ブレンダンは これをいくつかの分析にかけ 跡が見えますね 実際の成長輪の可視化に 成功しました つまり 水深500メートルのサンゴも 季節による変化を記録できるのです これには目を見張ります

しかし4000年では最終氷期の 最盛期には届きません ではどうするか? これらの化石標本を調査します このため 私は研究班で 実に不人気です 海底へ進んでいくと あちこちに大きなサメや ホヤそして泳ぐナマコ 大きな海綿動物がいます しかし私は研究員を 化石のある場所へ連れて行き ショベルで海底をすくうことに たっぷり時間をかけさせるのです そしてこれらのサンゴを全て収集して 持ち帰り 分類します それぞれ年齢が異なり もしも年齢が分かれば 化学信号の測定が可能で 過去に海で何が起きていたのかを 調査するのに役立ちます

左側の写真は サンゴの一部を採取し 注意深く磨いて 光学像を撮影したものです 右側の写真は 同じサンゴのかけらを原子炉に入れ 核分裂を誘発した画像です 核分裂のたびにその痕跡が サンゴに残されていくので ウランの分布がわかります この分析は何のためか? ウランはぜんぜん 評判の良くない元素ですが 私は好きです 崩壊によりその比率や 事象が起きた年代を測定できます 最初を思い出すと これこそ気候の調査で 突き止めたかったことです サンゴが含有するウランと 娘核種のトリウムを レーザーで分析すると 化石がちょうど何歳か 分かります

この南極海の美しい動画を使って 私たちがサンゴから 古代海洋の情報を ― どのように得るのか 説明していきましょう ライアン・アバナシーによる この動画で 海面の海水の密度が分かります たった1年分のデータですが 南極海がどれほど活発なのかが わかります ボックスが示す海水の密度が 集中的に混合している海域 ― 特にドレーク海峡は 世界で最も潮の流れが 荒い海域の一つで 潮は西から東へ通っていきます 海中の大きな山の上を流れるので 激しく混合し これが海中と大気中の 二酸化炭素と熱を交換可能にします 基本的に海は 南極海を介して呼吸しています 私たちは南極海の海峡を行来して サンゴを収集し ウラン年代測定により 驚くべき発見をしました 実は氷河期から間氷期へ 移行している間に サンゴは南から北へ 移動していたのです 理由は分かりませんが 食料や水中の酸素と 関連していると考えられます

さて ここからです 南極海のサンゴから得た 気候についての見解を説明します 私たちは海山を上って下り サンゴの化石を集めました これが私の説明です 私たちは独自のサンゴの分析により 氷河期を研究した結果 南極海の深部は炭素が豊富で 上部は低密度の海水の層であったと 知りました これが海から二酸化炭素を 放出しないようにします その後見つけた 中間年齢のサンゴにより 気候の遷移の中で 海水が混合したことが分かりました これにより炭素は深海から 放出されるようになります より現代に近いサンゴを 分析するか 実際にとにかく海底まで潜り サンゴを化学測定すれば 私たちは炭素が出入り可能な時代に 移ったのだと分かります こうして私たちはサンゴの化石を 環境を学ぶために役立てています

最後のスライドをご覧ください これは先ほど ご覧に入れた映像の抜粋です 見事なサンゴの庭園ですね 想像を絶する美しさです 数千メートルの水面下 新種の生物がいます とにかく美しい場所です ここにある化石全て そして深海にある サンゴの化石の真価を 皆さんにお伝えしました

今度幸運にも 飛行機で海を越えるか 航海する機会があれば 思い出してください 海底には ― 誰も見たことのない巨大な海山や 美しいサンゴの庭園があると

ありがとうございます

(拍手)

品詞分類

- 主語

- 動詞

- 助動詞

- 準動詞

- 関係詞等

TED 日本語

TED Talks

関連動画

騒がしい海の危険性―海をどのように静かできるのかニコラ・ジョーンズ

2020.04.16

風力ドローンによって海に対する私たちの考えが変わるセバスチャン・ド・ハルー

2018.12.11

オオジャコガイの知られざる魅惑的生態メイ・リン・ネオ

2017.10.12

なぜサンゴ礁にはまだ希望があるのかクリステン・マーハバー

2017.08.11

盲目の洞窟魚に見る先史時代へのヒントプロサンタ・チャクラバーティ

2016.08.09

海洋写真家の世界へ飛び込もうトーマス・ペスチャック

2016.03.21

暗闇で光るサメと驚くほど美しい海洋生物たちデビッド・グルーバー

2016.02.16

生命で輝きを増す海中美術館ジェイソン・デカイレス・テイラー

2016.01.22

幼生サンゴを育ててサンゴ礁を再生するには?クリステン・マーハバー

2015.12.23

なぜ鯨の糞が大切なのかアーシャ・デ・ボス

2015.01.05

水中で31日間を過ごして学んだことファビアン・クストー

2014.10.23

サメ除けウェットスーツ(あなたの想像とは違います)ハミッシュ・ジョリー

2014.04.23

ヒトはイルカの言葉を話せるだろうか?デニーズ・ハージング

2013.06.06

いかにして巨大イカを見つけたかエディス・ウィダー

2013.03.05

海洋生物調査ポール・スネルグローブ

2012.02.28

タコに魅せられてマイク・ディグリー

2012.02.05

洋楽 おすすめ

RECOMMENDS

洋楽歌詞

ダイナマイトビーティーエス

洋楽最新ヒット2020.08.20

ディス・イズ・ミーグレイテスト・ショーマン・キャスト

洋楽人気動画2018.01.11

グッド・ライフGイージー、ケラーニ

洋楽人気動画2017.01.27

ホワット・ドゥ・ユー・ミーン?ジャスティン・ビーバー

洋楽人気動画2015.08.28

ファイト・ソングレイチェル・プラッテン

洋楽人気動画2015.05.19

ラヴ・ミー・ライク・ユー・ドゥエリー・ゴールディング

洋楽人気動画2015.01.22

アップタウン・ファンクブルーノ・マーズ、マーク・ロンソン

洋楽人気動画2014.11.20

ブレイク・フリーアリアナ・グランデ

洋楽人気動画2014.08.12

ハッピーファレル・ウィリアムス

ポップス2014.01.08

カウンティング・スターズワンリパブリック

ロック2013.05.31

ア・サウザンド・イヤーズクリスティーナ・ペリー

洋楽人気動画2011.10.26

ユー・レイズ・ミー・アップケルティック・ウーマン

洋楽人気動画2008.05.30

ルーズ・ユアセルフエミネム

洋楽人気動画2008.02.21

ドント・ノー・ホワイノラ・ジョーンズ

洋楽人気動画2008.02.15

オンリー・タイムエンヤ

洋楽人気動画2007.10.03

ミス・ア・シングエアロスミス

ロック2007.08.18

タイム・トゥ・セイ・グッバイサラ・ブライトマン

洋楽人気動画2007.06.08

シェイプ・オブ・マイ・ハートスティング

洋楽人気動画2007.03.18

ウィ・アー・ザ・ワールド(U.S.A. フォー・アフリカ)マイケル・ジャクソン

洋楽人気動画2006.05.14

ホテル・カリフォルニアイーグルス

ロック2005.07.06