TED日本語

TED Talks(英語 日本語字幕付き動画)

TED日本語 - マイケル・ティルソン・トーマス: 音楽と感情の奏でる歴史

TED Talks

音楽と感情の奏でる歴史

Music and emotion through time

マイケル・ティルソン・トーマス

Michael Tilson Thomas

内容

この素晴らしい講演で、マイケル・ティルソン・トーマスがクラシック音楽の進化を表記方法や録音技術、そして編集方法の進化の観点から説明します。

字幕

SCRIPT

Script

Well when I was asked to do this TEDTalk, I was really chuckled, because, you see, my father's name was Ted, and much of my life, especially my musical life, is really a talk that I'm still having with him, or the part of me that he continues to be.

Now Ted was a New Yorker, an all-around theater guy, and he was a self-taught illustrator and musician. He didn't read a note, and he was profoundly hearing impaired. Yet, he was my greatest teacher. Because even through the squeaks of his hearing aids, his understanding of music was profound.

And for him, it wasn't so much the way the music goes as about what it witnesses and where it can take you. And he did a painting of this experience, which he called "In the Realm of Music." Now Ted entered this realm every day by improvising in a sort of Tin Pan Alley style like this. (Music)

But he was tough when it came to music. He said, "There are only two things that matter in music: what and how. And the thing about classical music, that what and how, it's inexhaustible."

That was his passion for the music. Both my parents really loved it. They didn't know all that much about it, but they gave me the opportunity to discover it together with them. And I think inspired by that memory, it's been my desire to try and bring it to as many other people as I can, sort of pass it on through whatever means. And how people get this music, how it comes into their lives, really fascinates me.

One day in New York, I was on the street and I saw some kids playing baseball between stoops and cars and fire hydrants. And a tough, slouchy kid got up to bat, and he took a swing and really connected. And he watched the ball fly for a second, and then he went, "Dah dadaratatatah. Brah dada dadadadah." And he ran around the bases. And I thought, go figure. How did this piece of 18th century Austrian aristocratic entertainment turn into the victory crow of this New York kid? How was that passed on? How did he get to hear Mozart?

Well when it comes to classical music, there's an awful lot to pass on, much more than Mozart, Beethoven or Tchiakovsky. Because classical music is an unbroken living tradition that goes back over 1,000 years. And every one of those years has had something unique and powerful to say to us about what it's like to be alive.

Now the raw material of it, of course, is just the music of everyday life. It's all the anthems and dance crazes and ballads and marches. But what classical music does is to distill all of these musics down, to condense them to their absolute essence, and from that essence create a new language, a language that speaks very lovingly and unflinchingly about who we really are. It's a language that's still evolving.

Now over the centuries it grew into the big pieces we always think of, like concertos and symphonies, but even the most ambitious masterpiece can have as its central mission to bring you back to a fragile and personal moment -- like this one from the Beethoven Violin Concerto. (Music) It's so simple, so evocative. So many emotions seem to be inside of it. Yet, of course, like all music, it's essentially not about anything. It's just a design of pitches and silence and time.

And the pitches, the notes, as you know, are just vibrations. They're locations in the spectrum of sound. And whether we call them 440 per second, A, or 3,729, B flat -- trust me, that's right -- they're just phenomena. But the way we react to different combinations of these phenomena is complex and emotional and not totally understood. And the way we react to them has changed radically over the centuries, as have our preferences for them.

So for example, in the 11th century, people liked pieces that ended like this. (Music) And in the 17th century, it was more like this. (Music) And in the 21st century ... (Music)

Now your 21st century ears are quite happy with this last chord, even though a while back it would have puzzled or annoyed you or sent some of you running from the room. And the reason you like it is because you've inherited, whether you knew it or not, centuries-worth of changes in musical theory, practice and fashion.

And in classical music we can follow these changes very, very accurately because of the music's powerful silent partner, the way it's been passed on: notation. Now the impulse to notate, or, more exactly I should say, encode music has been with us for a very long time. In 200 B.C., a man named Sekulos wrote this song for his departed wife and inscribed it on her gravestone in the notational system of the Greeks. (Music)

And a thousand years later, this impulse to notate took an entirely different form. And you can see how this happened in these excerpts from the Christmas mass "Puer Natus est nobis," "For Us is Born." (Music) In the 10th century, little squiggles were used just to indicate the general shape of the tune. And in the 12th century, a line was drawn, like a musical horizon line, to better pinpoint the pitch's location.

And then in the 13th century, more lines and new shapes of notes locked in the concept of the tune exactly, and that led to the kind of notation we have today. Well notation not only passed the music on, notating and encoding the music changed its priorities entirely, because it enabled the musicians to imagine music on a much vaster scale.

Now inspired moves of improvisation could be recorded, saved, considered, prioritized, made into intricate designs. And from this moment, classical music became what it most essentially is, a dialogue between the two powerful sides of our nature: instinct and intelligence.

And there began to be a real difference at this point between the art of improvisation and the art of composition. Now an improviser senses and plays the next cool move, but a composer is considering all possible moves, testing them out, prioritizing them out, until he sees how they can form a powerful and coherent design of ultimate and enduring coolness. Now some of the greatest composers, like Bach, were combinations of these two things. Bach was like a great improviser with a mind of a chess master. Mozart was the same way.

But every musician strikes a different balance between faith and reason, instinct and intelligence. And every musical era had different priorities of these things, different things to pass on, different 'whats' and 'hows'. So in the first eight centuries or so of this tradition the big 'what' was to praise God. And by the 1400s, music was being written that tried to mirror God's mind as could be seen in the design of the night sky. The 'how' was a style called polyphony, music of many independently moving voices that suggested the way the planets seemed to move in Ptolemy's geocentric universe. This was truly the music of the spheres. (Music)

This is the kind of music that Leonardo DaVinci would have known. And perhaps its tremendous intellectual perfection and serenity meant that something new had to happen -- a radical new move, which in 1600 is what did happen. (Music) Singer: Ah, bitter blow! Ah, wicked, cruel fate! Ah, baleful stars! Ah, avaricious heaven!

MTT: This, of course, was the birth of opera, and its development put music on a radical new course. The what now was not to mirror the mind of God, but to follow the emotion turbulence of man. And the how was harmony, stacking up the pitches to form chords.

And the chords, it turned out, were capable of representing incredible varieties of emotions. And the basic chords were the ones we still have with us, the triads, either the major one, which we think is happy, or the minor one, which we perceive as sad. But what's the actual difference between these two chords? It's just these two notes in the middle. It's either E natural, and 659 vibrations per second, or E flat, at 622. So the big difference between human happiness and sadness? 37 freakin' vibrations.

So you can see in a system like this there was enormous subtle potential of representing human emotions. And in fact, as man began to understand more his complex and ambivalent nature, harmony grew more complex to reflect it. Turns out it was capable of expressing emotions beyond the ability of words.

Now with all this possibility, classical music really took off. It's the time in which the big forms began to arise. And the effects of technology began to be felt also, because printing put music, the scores, the codebooks of music, into the hands of performers everywhere. And new and improved instruments made the age of the virtuoso possible. This is when those big forms arose -- the symphonies, the sonatas, the concertos.

And in these big architectures of time, composers like Beethoven could share the insights of a lifetime. A piece like Beethoven's Fifth basically witnessing how it was possible for him to go from sorrow and anger, over the course of a half an hour, step by exacting step of his route, to the moment when he could make it across to joy. (Music)

And it turned out the symphony could be used for more complex issues, like gripping ones of culture, such as nationalism or quest for freedom or the frontiers of sensuality. But whatever direction the music took,one thing until recently was always the same, and that was when the musicians stopped playing, the music stopped.

Now this moment so fascinates me. I find it such a profound one. What happens when the music stops? Where does it go? What's left? What sticks with people in the audience at the end of a performance? Is it a melody or a rhythm or a mood or an attitude? And how might that change their lives?

To me this is the intimate, personal side of music. It's the passing on part. It's the 'why' part of it. And to me that's the most essential of all. Mostly it's been a person-to-person thing, a teacher-student, performer-audience thing, and then around 1880 came this new technology that first mechanically then through analogs then digitally created a new and miraculous way of passing things on, albeit an impersonal one. People could now hear music all the time, even though it wasn't necessary for them to play an instrument, read music or even go to concerts.

And technology democratized music by making everything available. It spearheaded a cultural revolution in which artists like Caruso and Bessie Smith were on the same footing. And technology pushed composers to tremendous extremes, using computers and synthesizers to create works of intellectually impenetrable complexity beyond the means of performers and audiences.

At the same time technology, by taking over the role that notation had always played, shifted the balance within music between instinct and intelligence way over to the instinctive side. The culture in which we live now is awash with music of improvisation that's been sliced, diced, layered and, God knows, distributed and sold. What's the long-term effect of this on us or on music? Nobody knows.

The question remains: What happens when the music stops? What sticks with people? Now that we have unlimited access to music, what does stick with us?

Well let me show you a story of what I mean by "really sticking with us." I was visiting a cousin of mine in an old age home, and I spied a very shaky old man making his way across the room on a walker. He came over to a piano that was there, and he balanced himself and began playing something like this. (Music)

And he said something like, "Me ... boy ... symphony ... Beethoven." And I suddenly got it, and I said, "Friend, by any chance are you trying to play this?" (Music) And he said, "Yes, yes. I was a little boy. The symphony: Isaac Stern, the concerto, I heard it." And I thought, my God, how much must this music mean to this man that he would get himself out of his bed, across the room to recover the memory of this music that, after everything else in his life is sloughing away, still means so much to him?

Well, that's why I take every performance so seriously, why it matters to me so much. I never know who might be there, who might be absorbing it and what will happen to it in their life.

But now I'm excited that there's more chance than ever before possible of sharing this music. That's what drives my interest in projects like the TV series "Keeping Score" with the San Francisco Symphony that looks at the backstories of music, and working with the young musicians at the New World Symphony on projects that explore the potential of the new performing arts centers for both entertainment and education.

And of course, the New World Symphony led to the YouTube Symphony and projects on the internet that reach out to musicians and audiences all over the world. And the exciting thing is all this is just a prototype. There's just a role here for so many people -- teachers, parents, performers -- to be explorers together. Sure, the big events attract a lot of attention, but what really matters is what goes on every single day. We need your perspectives, your curiosity, your voices.

And it excites me now to meet people who are hikers, chefs, code writers, taxi drivers, people I never would have guessed who loved the music and who are passing it on. You don't need to worry about knowing anything. If you're curious, if you have a capacity for wonder, if you're alive, you know all that you need to know. You can start anywhere. Ramble a bit. Follow traces. Get lost. Be surprised, amused inspired. All that 'what', all that 'how' is out there waiting for you to discover its 'why', to dive in and pass it on.

Thank you.

(Applause)

今回TEDの講演を頼まれてつい うれしくなりました 亡き父の名もテッドだからです 私は日ごろから特に音楽に関しては 今でも私の心の中に生き続ける 父と会話をしています

テッドはニューヨーク出身で演劇界の仕事を何でもこなし 絵も描きましたしミュージシャンでもありました 楽譜は全く読めず 耳も良く聞こえなかったんです でも いろいろな事を 教えてくれました 補聴器からはきれいな音は聞こえなくても 父はとても良く音楽を理解していたんです

父にとって音楽とは単にどう聞こえるかではなく 何を描き 何を伝えるかだったのです 父はこの経験を絵に描きました 「音楽の世界で」というタイトルです 父は即興を通じて毎日この世界に入っていたのです この様な ティン・パン・アレーのスタイルで (音楽)

でも 父は音楽に対しては厳しく よく言いました「音楽で大切なのは2つだけ 『何』を『如何に』伝えるかだけだ クラシック音楽では これが無限にある」

こんな熱意を持って音楽に接していたのです 両親 二人とも音楽が大好きで あまり音楽に詳しくはありませんでしたが その素晴らしさを発見していく機会を与えてくれました その様に育ったせいか 音楽をより多くの人に楽しんで欲しいと 思うようになりました あらゆる方法で 音楽を伝えたいのです 人々の生活に音楽がどう入り込むかには とても興味があります

ある日通りを歩いていて 家の前で車や消火栓の間を使って野球をしている子供たちを見かけました 頑丈そうで もさっとした子が打席に立ち バットを振り しっかり球をとらえ 球が飛んでいくのを眺めると 「ラーラ ラーラ ラララララー ラーラ ラーラ ラララララー」と歌いながら ベースを回って行きました 信じられませんでした 18世紀のオーストリアの貴族が楽しんだものを ニューヨークの こんな子が勝利の歓声に使うなんて いったい この子はモーツァルトにどこで出会ったのでしょう

クラシック音楽は 音楽の宝庫です モーツァルト、ベートーベン チャイコフスキーに限りません クラシックは千年もの間 絶えず続いてきたものです そのすべての期間を通じて 生きるとは何かについて 独特な方法で力強く 伝えてきたのです

題材はもちろん 日々の暮らしに基づいた音楽で 国歌や 流行のダンス バラードとか行進曲とかですが クラシック音楽はそこから 不純物を取り除き 核心となるものに凝縮して そこから新しい言葉を作り出しているのです その言葉は私たちの本質を見つめ とてつもなく美しく奏でるのです この言葉は今でも進化し続けています

年月を経て人々に親しまれる 協奏曲とか交響曲となりましたが どんな大がかりな名作でも 核心にある動機は 聞く人 それぞれの持つデリケートな感覚を呼び戻すことです 例えばこのベートーベンのバイオリン協奏曲です (音楽) とてもシンプルですが 強い感情を引き起こします たくさんの感情が隠れているようです でも どの音楽も それ自体 意味はないんです 音の高低や静寂 タイミングを 組み合わせただけなんです

音符で表される音の高さは単なる振動で 聞こえる周波数域の特定の場所を示しているにすぎません 毎秒440回の振動と呼ぶか それを「ラ」と呼ぶか 3729回なら「シのフラット」か それは単なる現象です でもこの現象の組み合わせ方によって 私たちは複雑に感情的に反応しますが その仕組みは完全にわかっていません 反応の仕方も歴史とともに変化し 好みも変わっています

例えば 11世紀には 音楽はこの様に終わるのが好まれていました (音楽) 17世紀になると このように変わります (音楽) 21世紀になると こうです (音楽)

21世紀のみなさんは このようなコードを「いいな」なんて思うのですが 少し前までは理解に苦しみ 不快に感じたり 逃げ出したくなったかもしれません 心地よく感じるようになったのは 意識的にか無意識に 何百年という間に起こった 音楽理論、習慣、流行を受け継いできたからです

クラシック音楽では この変化を かなり正確に理解する事ができます 音楽の静かなパートナー 音楽を後世に伝えてきた「楽譜」を見るとわかります 音楽を書き留めたい-- コード化と呼んだ方が正確かと思いますが この思いは かなり昔からあるものです 紀元前200年頃 セイキロスという人が 旅立った妻のためにこの曲を書き ギリシャ当時のシステムで墓石に刻みました (音楽)

千年後には 表記に対する志はかなり違った形態のものを生み出しました これをご覧下さい 『我らに幼な子が生まれ給えり』というクリスマス・ミサで歌われる 曲の一部です (音楽) 10世紀にはくねっとした線で 曲の大まかな形が記録されました 12世紀になると譜線のような水平な線が現れます これで音程の場所が少しはっきりします

13世紀になると 線の数が増え音符の形も変わり 音程の概念が しっかりと根付きます そして 現在の様な表記法になりました このような表記によって音楽が後世に残されただけでなく 音楽のありかたを変えてしまいました 書き留めることによって 作曲家が音楽を大きなスケールで捉えられるようになったのです

即興で思いついたメロディーを 書き留め保存し 考えて整理し 複雑なものに構築できます これによって クラシック音楽の 中心となるものは 人間の2つの能力である 直感と知性の対話になりました

これを期して 音楽というものが 即興の芸術と 構成の芸術に 分かれたのです 即興をする人は次に来る粋なフレーズを感じそれを演奏します 構成を好む人は 可能な様々なフレーズを吟味し 試したり 並べてみて インパクトがあり バランスの取れた 「これだ」という 絶対的なものが見つかるまで 試行錯誤を繰り返します さて偉大な作曲家 バッハなどは 即興と構成の両方の能力の持ち主です バッハは即興も得意でしたが チェスの王者の様な頭脳を持ち合わせていました モーツァルトも同様です

でも それぞれの音楽家によってこのバランスは違っています 信念と理屈 直感と知能 時代によって これらの重要性が変わり 「何」を「如何に」伝えるかも変わってきたのです 最初の8世紀ほどは 「何」にあたるものは神を崇めることでした 1400年代になると 音楽は 神の心をなぞらえようと 夜空のようなデザインになりました 「如何に」にあたる手法はポリフォニーと呼ばれる 独立した複数のメロディーです プトレマイオスの天動説に基づいた地球を中心に動く天体を 表しているかのようです 真に天体の世界の音楽です (音楽)

レオナルド・ダヴィンチはこんな音楽を聞いていたはずです 知的な完璧さと静寂 これは新しい変化が必要になります そして 1600年代に全く新しい変化が起こりました (音楽) 歌手: ああ 恐ろしいこと ああ なんていう運命 ああ 不吉な星 情けのない天なのだろう

これはもちろんオペラ時代の始まりです オペラの発展は音楽を全く新しい方向に発展させました 「何」で伝えるものは神の心の反映ではなく 人の心の浮き沈みを描くようになり 「どう」伝えるかの手段はハーモニーになりました 異なる音を組み合わせた和音です

和音を使うと 実に沢山の感情を表す事ができるとわかりました 基本的な和音は今でも使っています お馴染みの三和音 です 長三和音 は うれしく聞こえ 短三和音 であれば 悲しく聞こえます でもこの2つの和音の違いはなんでしょう 音階の中央付近にある この2音だけです 「ミ」がナチュラルで 毎秒 659回振動しているか 「ミ」がフラットで 622回かの違いです 人間が幸せか 悲しいかの違いは なんと たった37回の振動数の違いなんです

ですから このようなシステムでは 人間の微妙な感情を表現出来る可能性が膨大にあるわけです 実際 人間が自分達の複雑で不安定な 感情を認識するにつれ 旋律もそれを反映し次第に複雑になりました 音楽は言葉で表せないことまで 表現できるのです

この可能性を踏まえ クラシック音楽は大きく変わりました 大きな形式が作られ始め 技術の発達による影響も感じられるようになりました 印刷技術の発達により暗号として楽譜に記された音楽は 様々な所にいる演奏家の手に渡ります 新しい楽器や 改善された楽器のおかげで 演奏のレベルが上がります 次第に 大きな形式がうまれました 交響曲やソナタ 協奏曲など

当時の大きな構築物で ベートーベンのような音楽家は人生を垣間見せてくれるのです ベートーベンの5番を聞くと 悲しみや怒りから30分くらいの間に 彼の注意深く敷いた道をたどって 喜びにたどり着けるのです (音楽)

交響曲はもっと複雑なことにも使えます 心をひきつける人間の活動 例えば愛国主義や自由への願望や さらには 官能的なものにも迫ります しかし 音楽がどのような方向をとっても 最近まで 変わらぬことがありました それはミュージシャンが演奏をやめると 音楽も止まってしまうことでした

これはとても興味のある瞬間です とても大切な瞬間です 音楽が止むとどうなるか? 音楽はどこに行ってしまうのか?何か残るのだろうか? 演奏を聴いた人の耳に何が残るだろうか? メロディーかリズムか 感覚かそれとも姿勢か そして 聞いた人の人生がどう変わるだろうか

これは私にとって 音楽が持つ親密でプライベートな一面です 伝えるということ「なぜ」音楽をするかということです 私にとって一番大切な部分です 音楽がもたらす影響は人から人へと伝えられるものでした 先生から生徒にとか 演奏家から観客 ところが1880年頃に新しい技術がもたらされました 最初は機械的で 後にアナログを経てデジタルになりました これで音楽を驚くような方法で伝える事が可能になりました 人間性はありませんが だれでも いつでも音楽を聴くことができます 楽器や譜を読む知識も要りません演奏会に行く必要もないのです

技術のおかげで 音楽が民主化され皆の手に入るようになったのです これは文化革命につながります カルーソー(テノール歌手)やベッシー・スミス(ブルース歌手)を同じ尺度で考えることが出来るのです 技術は作曲家のレベルも押し上げます コンピューターやシンセサイザーを使い知性では不可能なほど複雑な 演奏家や聞く人の理解を超えるものを作れるようになりました

同時に技術は 表記のもたらした 直感と知性のバランスを 逆に直感重視に傾かせました 現在の風潮では 音楽は即興性にあふれ 切り刻まれ 再構築され 市場に出回ります これが 将来音楽に与える影響は何でしょう わかりません

でも 疑問は変わりません音楽を聞き終わったとき 人々の心に何が残るか? 音楽が溢れるほど存在するこの時代に 何が心に残るのでしょう?

心に焼きつくものとは何を意味するのか ひとつ例をご紹介しましょう 従兄弟を訪ねるため老人ホームに行きました そこで弱々しい年配の男性が 歩行器を使って部屋を横切り ピアノの所まで来ると なんとか体のバランスをとりながらこんな風に弾き始めました (音楽)

そして「僕...子供...交響曲...ベートーベン」と口にしました それを聞いて分かったんです 「すみません もしかしたらこれのことですか?」 (音楽) それを聞いて「そうそう 私が小さい頃 交響曲..アイザック・スターンの協奏曲聞いたんです」 それを聞いて びっくりしました この曲がこの人にとってどんなに大切かわかります ベッドから起き上がり部屋を歩いて この曲の記憶を呼び戻すのが 全てのものを失いつつある今でも そんなに意味のあるものなのです

だから 私は一回一回の演奏を真剣に受け止め 大切にするんです 誰が聴いているかわからない誰の心に吸収され その影響もわかりません

今まで以上に 様々な人と音楽を楽しめる時代になり とても素晴らしい事だと思います サンフランシスコ交響楽団と共同制作の 『Keeping Score』というテレビ番組のシリーズでは 音楽の背景を探索したり ニュー・ワールド交響楽団の若い音楽家とともに エンターテイメントと教育のための新しいコンサートホールを 模索するプロジェクトも行なっています

もちろん ニュー・ワールド交響楽団から YouTube シンフォニーや他のネット上のプロジェクトが生まれました 世界中のミュージシャンや観衆につながろうとする試みです これらは単なる試みの一例で いろいろな人が いろいろな事をできるんです 先生や親演奏家が一緒になって いろいろな事を模索できます 大きな企画は注目を集めますが 大切なのは日頃の行いで みなさんの考えや 探求心意見が必要です

いろいろな人に会ってうれしくなることがあります 旅人や料理人プログラマーや タクシーの運転手 音楽愛好家だなんて思わなかった人たちが 音楽を伝えている 知識なんてなくても 好奇心があってもっと知りたいと 生き生きとしていれば それで充分です 何をしてもいいんです あてもなくウロウロしたり 何かを追っても良い迷い 驚き 楽しみ 刺激を受けてください 「何」を「如何に」伝えるかたくさんのものが存在しています 皆さんが「なぜ」そうするのか発見し その世界に飛び込んで それを伝えていくのを待っているのです

ありがとうございました

(拍手)

品詞分類

- 主語

- 動詞

- 助動詞

- 準動詞

- 関係詞等

TED 日本語

TED Talks

関連動画

素晴らしいアイデアの見つけ方OK Go

2017.06.16

しびれるようなアコースティック・ギターの演奏ロドリーゴ・イ・ガブリエーラ

2017.03.09

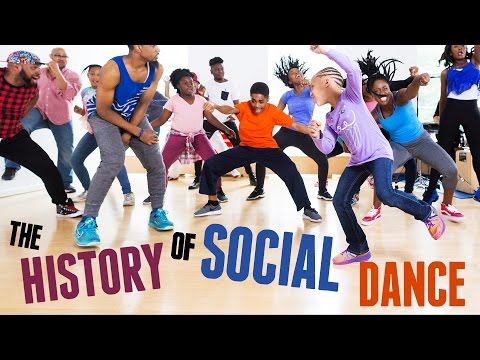

25のムーブから見る、アメリカの大衆ダンスの歴史カミーユ・A・ブラウン

2016.10.20

『リデンプション・ソング(あがないの歌)』ジョン・レジェンド

2016.08.10

音楽の力で光と色の世界へカーキ・キング

2015.12.03

11歳の神童が奏でるモダンジャズピアノジョーイ・アレキサンダー

2015.06.19

一人5役の女性による、セックスについての未来の授業サラ・ジョーンズ

2015.06.09

終身刑に服する女性たちの感動の歌声ザ・レディー・ライファーズ

2015.05.15

私のヒーロー、ハリケーンに向かってボートを漕いだ女性に贈る歌ドーン・ランデス

2015.05.08

ダンサー、シンガー、チェリストによる、目を見張るような創造の瞬間ビル・T・ジョーンズ

2015.05.06

マジックでたどる「偶然」を探す旅ヘルダー・ギマレス

2015.02.27

渦巻く紙と風と光の中のダンスアカシュ・オデドラ

2014.12.05

なぜピアノを路上や空中に持ち出すのかダリア・ファン・ベルケン

2014.10.03

どうか皆さんお願いします “awesome”に本来のawe(畏敬)の意味を取り戻しましょうジル・シャーガー

2014.08.29

あなたは人間ですか?ゼイ・フランク

2014.07.18

2つのマニアックなこだわりが出会うところ ― それはマジックデヴィッド・クォン

2014.07.11

洋楽 おすすめ

RECOMMENDS

洋楽歌詞

ステイザ・キッド・ラロイ、ジャスティン・ビーバー

洋楽最新ヒット2021.08.20

スピーチレス~心の声ナオミ・スコット

洋楽最新ヒット2019.05.23

シェイプ・オブ・ユーエド・シーラン

洋楽人気動画2017.01.30

フェイデッドアラン・ウォーカー

洋楽人気動画2015.12.03

ウェイティング・フォー・ラヴアヴィーチー

洋楽人気動画2015.06.26

シー・ユー・アゲインウィズ・カリファ

洋楽人気動画2015.04.06

シュガーマルーン5

洋楽人気動画2015.01.14

シェイク・イット・オフテイラー・スウィフト

ポップス2014.08.18

オール・アバウト・ザット・ベースメーガン・トレイナー

ポップス2014.06.11

ストーリー・オブ・マイ・ライフワン・ダイレクション

洋楽人気動画2013.11.03

コール・ミー・メイビーカーリー・レイ・ジェプセン

洋楽人気動画2012.03.01

美しき生命コールドプレイ

洋楽人気動画2008.08.04

バッド・デイ~ついてない日の応援歌ダニエル・パウター

洋楽人気動画2008.05.14

サウザンド・マイルズヴァネッサ・カールトン

洋楽人気動画2008.02.19

イッツ・マイ・ライフボン・ジョヴィ

ロック2007.10.11

アイ・ウォント・イット・ザット・ウェイバックストリート・ボーイズ

洋楽人気動画2007.09.14

マイ・ハート・ウィル・ゴー・オンセリーヌ・ディオン

洋楽人気動画2007.07.12

ヒーローマライア・キャリー

洋楽人気動画2007.03.21

オールウェイズ・ラヴ・ユーホイットニー・ヒューストン

洋楽人気動画2007.02.19

オネスティビリー・ジョエル

洋楽人気動画2005.09.16