TED日本語

TED Talks(英語 日本語字幕付き動画)

TED日本語 - ダン・バーケンストック: 世界は一つのデータセットです。それをどのように撮影するのかというと・・・

TED Talks

世界は一つのデータセットです。それをどのように撮影するのかというと・・・

The world is one big dataset. Now, how to photograph it ...

ダン・バーケンストック

Dan Berkenstock

内容

衛星画像は我々にとって身近なものですが、それらの多くが実は古いデータです。というのも人工衛星は大きくて高価なので、それ程たくさん存在しないからです。ダン・バーケンストックは新たな解決策を提案します。それはリアルタイムで地上を撮影可能な新型の小型人工衛星です。

字幕

SCRIPT

Script

Five years ago, I was a Ph.D. student living two lives. In one, I used NASA supercomputers to design next-generation spacecraft, and in the other I was a data scientist looking for potential smugglers of sensitive nuclear technologies. As a data scientist, I did a lot of analyses, mostly of facilities, industrial facilities around the world. And I was always looking for a better canvas to tie these all together. And one day, I was thinking about how all data has a location, and I realized that the answer had been staring me in the face. Although I was a satellite engineer, I hadn't thought about using satellite imagery in my work.

Now, like most of us, I'd been online, I'd see my house, so I thought, I'll hop in there and I'll start looking up some of these facilities. And what I found really surprised me. The pictures that I was finding were years out of date, and because of that, it had relatively little relevance to the work that I was doing today. But I was intrigued. I mean, satellite imagery is pretty amazing stuff. There are millions and millions of sensors surrounding us today, but there's still so much we don't know on a daily basis. How much oil is stored in all of China? How much corn is being produced? How many ships are in all of our world's ports? Now, in theory, all of these questions could be answered by imagery, but not if it's old. And if this data was so valuable, then how come I couldn't get my hands on more recent pictures?

So the story begins over 50 years ago with the launch of the first generation of U.S. government photo reconnaissance satellites. And today, there's a handful of the great, great grandchildren of these early Cold War machines which are now operated by private companies and from which the vast majority of satellite imagery that you and I see on a daily basis comes. During this period, launching things into space, just the rocket to get the satellite up there, has cost hundreds of millions of dollars each, and that's created tremendous pressure to launch things infrequently and to make sure that when you do, you cram as much functionality in there as possible. All of this has only made satellites bigger and bigger and bigger and more expensive, now nearly a billion, with a b, dollars per copy. Because they are so expensive, there aren't very many of them. Because there aren't very many of them, the pictures that we see on a daily basis tend to be old.

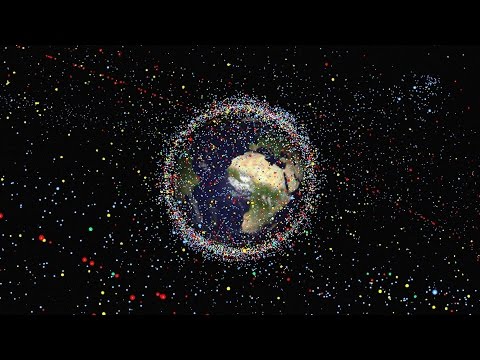

I think a lot of people actually understand this anecdotally, but in order to visualize just how sparsely our planet is collected, some friends and I put together a dataset of the 30 million pictures that have been gathered by these satellites between 2000 and 2010. As you can see in blue, huge areas of our world are barely seen, less than once a year, and even the areas that are seen most frequently, those in red, are seen at best once a quarter. Now as aerospace engineering grad students, this chart cried out to us as a challenge. Why do these things have to be so expensive? Does a single satellite really have to cost the equivalent of three 747 jumbo jets? Wasn't there a way to build a smaller, simpler, new satellite design that could enable more timely imaging?

I realize that it does sound a little bit crazy that we were going to go out and just begin designing satellites, but fortunately we had help. In the late 1990s, a couple of professors proposed a concept for radically reducing the price of putting things in space. This was hitchhiking small satellites alongside much larger satellites. This dropped the cost of putting objects up there by over a factor of 100, and suddenly we could afford to experiment, to take a little bit of risk, and to realize a lot of innovation. And a new generation of engineers and scientists, mostly out of universities, began launching these very small, breadbox-sized satellites called CubeSats. And these were built with electronics obtained from RadioShack instead of Lockheed Martin.

Now it was using the lessons learned from these early missions that my friends and I began a series of sketches of our own satellite design. And I can't remember a specific day where we made a conscious decision that we were actually going to go out and build these things, but once we got that idea in our minds of the world as a dataset, of being able to capture millions of data points on a daily basis describing the global economy, of being able to unearth billions of connections between them that had never before been found, it just seemed boring to go work on anything else.

And so we moved into a cramped, windowless office in Palo Alto, and began working to take our design from the drawing board into the lab. The first major question we had to tackle was just how big to build this thing. In space, size drives cost, and we had worked with these very small, breadbox-sized satellites in school, but as we began to better understand the laws of physics, we found that the quality of pictures those satellites could take was very limited, because the laws of physics dictate that the best picture you can take through a telescope is a function of the diameter of that telescope, and these satellites had a very small, very constrained volume. And we found that the best picture we would have been able to get looked something like this. Although this was the low-cost option, quite frankly it was just too blurry to see the things that make satellite imagery valuable. So about three or four weeks later, we met a group of engineers randomly who had worked on the first private imaging satellite ever developed, and they told us that back in the 1970s, the U.S. government had found a powerful optimal tradeoff -- that in taking pictures at right about one meter resolution, being able to see objects one meter in size, they had found that they could not just get very high-quality images, but get a lot of them at an affordable price. From our own computer simulations, we quickly found that one meter really was the minimum viable product to be able to see the drivers of our global economy, for the first time, being able to count the ships and cars and shipping containers and trucks that move around our world on a daily basis, while conveniently still not being able to see individuals. We had found our compromise. We would have to build something larger than the original breadbox, now more like a mini-fridge, but we still wouldn't have to build a pickup truck. So now we had our constraint. The laws of physics dictated the absolute minimum-sized telescope that we could build.

What came next was making the rest of the satellite as small and as simple as possible, basically a flying telescope with four walls and a set of electronics smaller than a phone book that used less power than a 100 watt lightbulb. The big challenge became actually taking the pictures through that telescope. Traditional imaging satellites use a line scanner, similar to a Xerox machine, and as they traverse the Earth, they take pictures, scanning row by row by row to build the complete image. Now people use these because they get a lot of light, which means less of the noise you see in a low-cost cell phone image. The problem with them is they require very sophisticated pointing. You have to stay focused on a 50-centimeter target from over 600 miles away while moving at more than seven kilometers a second, which requires an awesome degree of complexity. So instead, we turned to a new generation of video sensors, originally created for use in night vision goggles. Instead of taking a single, high quality image, we could take a videostream of individually noisier frames, but then we could recombine all of those frames together into very high-quality images using sophisticated pixel processing techniques here on the ground, at a cost of one one hundredth a traditional system. And we applied this technique to many of the other systems on the satellite as well, and day by day, our design evolved from CAD to prototypes to production units.

A few short weeks ago, we packed up SkySat 1, put our signatures on it, and waved goodbye for the last time on Earth. Today, it's sitting in its final launch configuration ready to blast off in a few short weeks. And soon, we'll turn our attention to launching a constellation of 24 or more of these satellites and beginning to build the scalable analytics that will allow us to unearth the insights in the petabytes of data we will collect.

So why do all of this? Why build these satellites? Well, it turns out imaging satellites have a unique ability to provide global transparency, and providing that transparency on a timely basis is simply an idea whose time has come. We see ourselves as pioneers of a new frontier, and beyond economic data, unlocking the human story, moment by moment. For a data scientist that just happened to go to space camp as a kid, it just doesn't get much better than that.

Thank you.

(Applause)

5年前 私は2足のわらじを履く 博士課程の学生でした 一つ目ですが NASAのスーパーコンピュータを使っていました 次世代の宇宙船を作るためです 二つ目ですが 私はデータサイエンティストでした 原子力の機密データを盗み出す 可能性のある人間を探し出していました データサイエンティストとして いろいろな解析をしました 世界中の多くの産業施設の解析です そして これらすべてを結びつける 良いアイディアを探していました ある日 すべてのデータがどのように 位置情報を持っているかを考えていました そして気づいたのです 目の前に答えがあることに 私は人工衛星のエンジニアですが 自分の仕事に衛星画像を使うことは 考えたことがありませんでした

今では 皆さんと同じく 私はオンライン環境にあり 自分の家をみることができます それなら そこに飛び込んで その施設を探してみようと そして 驚くべきことがわかりました 私が探していた写真は 何年も前のものでした 今の仕事に 何の役にも立たなかったのです でも そこに興味がわきました 衛星画像はとてもすばらしいものだと いまでは無数の衛星が私たちの周りを 取り巻いています でも 私達には知らないことばかりです 中国の石油の備蓄量は? コーンの生産量は? 世界中の港に停泊している船舶数は? 理論的には 衛星画像により そうした質問に答えることができます ただし その写真が古くなければです こういった画像に価値があるのならば どうして最新のデータを 入手できないのでしょうか

こういった話は50年前からありました 米国政府が偵察用の衛星を 初めて打ち上げた時からです 今では 冷戦時代に作られた 衛星の後継機の多くが 民間企業によって運用されていて 多くの私たちが目にする写真は それらの衛星が撮影したものなのです 現在 ロケットで宇宙へ 衛星を送り込むだけでも 数百万ドルかかります 時々しか飛ばさないので 大きなプレッシャーです そして たくさんの機能を詰め込みます こうして 人工衛星は 巨大化し 費用がかさみ 1台あたり約10億ドルもするようになりました とても高価なので 人工衛星はそれほど存在しないのです そのため普段 我々が見る画像は 古くなりがちです

実際に 多くの人が理解していますが 地球上の収集データが 点在していることを 可視化するために 2000年から2010年の間に 衛星が収集した 3000万枚のデータをまとめました 広大な青色の部分 ここが撮影されるのは年1回以下です 赤い部分は頻繁に撮影されますが それでも3ヶ月に1回もありません 航空宇宙工学の卒業生にとって このデータは 大きな挑戦を投げかけます どうしてこのデータは高価なのでしょうか? 衛星一機あたり ボーイング747機3台分の 費用もかかるのはなぜでしょうか? より小さくシンプルな新型衛星を 作る方法はないのでしょうか? タイムリーに撮影できる人工衛星です

ちょっとおかしいのはわかっていますが 我々は新型衛星の設計に着手しました 運良く手助けしてもらえたのです 1990年代後半に 数名の教授が 宇宙に機器を搬送する費用を 著しく減らす方法を考えました 小さな衛星をヒッチハイクするのです より大きな衛星のそばにある これによりコストは 100分の1以下に下がりました そして突然ですが 実験できるようになり 多くのイノベーションを実現しました 新しい世代のエンジニアや科学者が 多くは大学の者ですが 「CubeSats」と呼ばれる パン入れサイズの小型衛星を打ち上げ始めました これはホームセンターで手に入れた 電子部品でできており

友人と衛星のデザインを始めた 開発初期のアイデアが活かされています 衛星開発の決断をした 具体的な日は思い出せませんが この世界を一つのデータセットと捉え 世界経済を表す 大量のデータを取得し 今まで知られていなかった関係性を掘り起こす そんなアイデアを思いついた日から それ以外の仕事には目もくれなくなりました

私たちはPalo Altoにある 窓もないオフィスに缶詰めになり 単なるデザインを元に 試作機の開発を進めました 解決しなければならない最初の問題は モノの大きさでした 宇宙では サイズはコストに直結します 小さなパン入れサイズの衛星の 製作に取り掛かっていましたが 物理法則から この衛星の画質の限界を知ります その物理法則によると 望遠鏡で見える画質は 望遠鏡の直径に依存します 私たちの衛星はとても小さかったのです 予想されていた画質はこのくらいでした 安くて済むけれども ぼやけ過ぎていて はっきり言って 役に立ちそうにありません そこで3、4週間の間に いろんなエンジニアに会いました 彼らは初期の個人衛星開発に携わっていました 彼らによると1970年代 米国政府は強力で 最適なトレードオフを見つけました 1mの解像度で画像を撮ると 1mのサイズでものが見えます 高画質ではなかったけれど 程よい値段で画像が撮れました シミュレーションから初めてわかったのは グローバル経済の担い手を見るのに 最低限1mは必要ということです 担い手というのは 我々の身の回りにある 船 車 輸送コンテナ トラックのことです 人間を数えることはできませんが 妥協点を見つけました パン入れよりも大きな衛星を 作らなくてはいけない 小さな冷蔵庫くらいでしょうか 軽トラックほど 大きい必要はありません 物理学的な制約により 望遠鏡の最小サイズはわかりました

次の問題は 衛星の残りの部分を どれだけ小さくシンプルにするかです 四方を囲まれた箱に入る望遠鏡と 電話帳よりも小さく 100Wも消費しない 電子機器をどうするかということです 大きな課題は望遠鏡を通して 実際に画像を撮ることです 古くからある衛星写真は ラインスキャナを使います それはコピー機に似ています 地球を横切りながら写真を撮ります 何度も繰り返しスキャンし 画像を完成させます 光量が多く 現在主流の方法です ノイズを低減でき 低価格の携帯電話で使われています その課題は 非常に精密な ポインティングが必要であることです 上空1000kmから 50cmの目標物を とらえ続けなくてはなりません 秒速7kmで飛行中にです これはとても高度なことです そこで次世代ビデオセンサーに 目をつけました 元々は暗視ゴーグルに 使われていたものです 高画質画像を使う代わりに ビデオストリームを使います 一枚一枚にはノイズが乗りますが それらを組み合わせて 高画質の画像にすることができます 高精度な画像処理技術が それを可能にします コストは従来の1/100です 私たちはこの技術を 衛星の他のシステムにも適用しました 日々 私たちの設計は進化しました CADからプロトタイプ 完成品へと

数週間前 SkySat 1号を完成させ サインをしました 地球上での最後の時に 向け別れを告げました 今は 発射台に据え付けられ あと数週間で発射されます そして すぐに 24基以上の衛星を 打ち上げる予定です そして大規模な分析を始めます ペタバイト級のデータから いろいろな洞察ができるでしょう

我々の目的は? どうして衛星を作るのか? 要するに 衛星画像は 世界規模の透明性を与え リアルタイムの透明性は 今まさに必要とされているものです 私たちは新しい時代を築いています そして 単なる経済データを越えて 少しずつ 人類の物語を 解き明かすでしょう データサイエンティストとして スペースキャンプに行く子供のような気分です これほどワクワクすることは他にありません

ありがとうございました

(拍手)

品詞分類

- 主語

- 動詞

- 助動詞

- 準動詞

- 関係詞等

TED 日本語

TED Talks

関連動画

謎に包まれた土星の衛星タイタンを調べて生命の起源に関して何がわかるかエリザベス・ジビ・タートル

2020.09.17

宇宙に関する理解に疑問を抱かせる珍しい銀河ブーチン・ムトゥル・パクディル

2018.09.18

宇宙人はどこにいるのでしょう?スティーヴン・ウェッブ

2018.08.16

他の恒星系からの初の訪問者オウムアムアカレン・J・ミーチ

2018.07.19

地球上で最も火星によく似た場所アルマンド・アズア・ブストス

2017.10.05

あなたは皆既日食を是非体験すべきであるデイヴィッド・バロン

2017.08.10

ブラックホールの写真を撮影するケイティ・バウマン

2017.04.28

地球を周回している宇宙ゴミを片付けましょうナタリー・パネク

2017.01.05

地球外生命を宿しているかもしれない1つの惑星と3つの衛星ジェームズ・グリーン

2016.09.07

惑星が生命を育むために必要なものデイヴ・ブレイン

2016.09.04

火星に移住する子供達が生き抜く方法スティーブン・ペトラネック

2016.05.05

宇宙でもっとも神秘的な星タベサ・ボヤジアン

2016.04.29

重力波発見が意味することアラン・アダムス

2016.03.10

他の惑星の生命を見つけ出す方法アオマワ・シールズ

2016.01.28

物理学は終焉に達したのか?ハリー・クリフ

2016.01.26

火星は予備の地球ではないルシアン・ウォーコウィッチ

2016.01.14

洋楽 おすすめ

RECOMMENDS

洋楽歌詞

ステイザ・キッド・ラロイ、ジャスティン・ビーバー

洋楽最新ヒット2021.08.20

スピーチレス~心の声ナオミ・スコット

洋楽最新ヒット2019.05.23

シェイプ・オブ・ユーエド・シーラン

洋楽人気動画2017.01.30

フェイデッドアラン・ウォーカー

洋楽人気動画2015.12.03

ウェイティング・フォー・ラヴアヴィーチー

洋楽人気動画2015.06.26

シー・ユー・アゲインウィズ・カリファ

洋楽人気動画2015.04.06

シュガーマルーン5

洋楽人気動画2015.01.14

シェイク・イット・オフテイラー・スウィフト

ポップス2014.08.18

オール・アバウト・ザット・ベースメーガン・トレイナー

ポップス2014.06.11

ストーリー・オブ・マイ・ライフワン・ダイレクション

洋楽人気動画2013.11.03

コール・ミー・メイビーカーリー・レイ・ジェプセン

洋楽人気動画2012.03.01

美しき生命コールドプレイ

洋楽人気動画2008.08.04

バッド・デイ~ついてない日の応援歌ダニエル・パウター

洋楽人気動画2008.05.14

サウザンド・マイルズヴァネッサ・カールトン

洋楽人気動画2008.02.19

イッツ・マイ・ライフボン・ジョヴィ

ロック2007.10.11

アイ・ウォント・イット・ザット・ウェイバックストリート・ボーイズ

洋楽人気動画2007.09.14

マイ・ハート・ウィル・ゴー・オンセリーヌ・ディオン

洋楽人気動画2007.07.12

ヒーローマライア・キャリー

洋楽人気動画2007.03.21

オールウェイズ・ラヴ・ユーホイットニー・ヒューストン

洋楽人気動画2007.02.19

オネスティビリー・ジョエル

洋楽人気動画2005.09.16