TED日本語

TED Talks(英語 日本語字幕付き動画)

TED日本語 - ジョナサン・トレント: 次世代バイオ燃料生産、海に浮かべる藻のゆりかご

TED Talks

次世代バイオ燃料生産、海に浮かべる藻のゆりかご

Energy from floating algae pods

ジョナサン・トレント

Jonathan Trent

内容

化石燃料の代替となる燃料の開発に向け、ジョナサン・トレント は都市部からの排水を栄養源とする微細藻類から 次世代バイオ燃料を得るプロジェクトに取り組んでいます。今回の講演では 彼が率いるプロジェクトOMEGA(海上藻類養殖用膜質容器)の大胆なビジョンと、これを新しいエネルギー源として普及させるための可能性についてお話します。

字幕

SCRIPT

Script

Some years ago, I set out to try to understand if there was a possibility to develop biofuels on a scale that would actually compete with fossil fuels but not compete with agriculture for water, fertilizer or land.

So here's what I came up with. Imagine that we build an enclosure where we put it just underwater, and we fill it with wastewater and some form of microalgae that produces oil, and we make it out of some kind of flexible material that moves with waves underwater, and the system that we're going to build, of course, will use solar energy to grow the algae, and they use CO2, which is good, and they produce oxygen as they grow. The algae that grow are in a container that distributes the heat to the surrounding water, and you can harvest them and make biofuels and cosmetics and fertilizer and animal feed, and of course you'd have to make a large area of this, so you'd have to worry about other stakeholders like fishermen and ships and such things, but hey, we're talking about biofuels, and we know the importance of potentially getting an alternative liquid fuel.

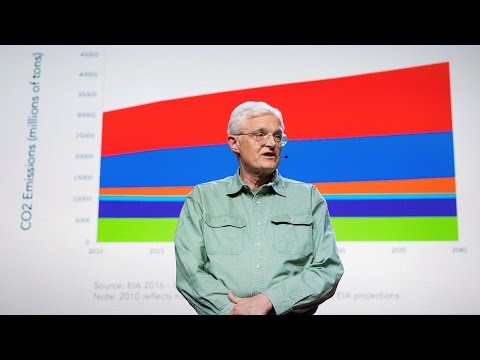

Why are we talking about microalgae? Here you see a graph showing you the different types of crops that are being considered for making biofuels, so you can see some things like soybean, which makes 50 gallons per acre per year, or sunflower or canola or jatropha or palm, and that tall graph there shows what microalgae can contribute. That is to say, microalgae contributes between 2,000 and 5,000 gallons per acre per year, compared to the 50 gallons per acre per year from soy.

So what are microalgae? Microalgae are micro -- that is, they're extremely small, as you can see here a picture of those single-celled organisms compared to a human hair. Those small organisms have been around for millions of years and there's thousands of different species of microalgae in the world, some of which are the fastest-growing plants on the planet, and produce, as I just showed you, lots and lots of oil.

Now, why do we want to do this offshore? Well, the reason we're doing this offshore is because if you look at our coastal cities, there isn't a choice, because we're going to use waste water, as I suggested, and if you look at where most of the waste water treatment plants are, they're embedded in the cities. This is the city of San Francisco, which has 900 miles of sewer pipes under the city already, and it releases its waste water offshore. So different cities around the world treat their waste water differently. Some cities process it. Some cities just release the water. But in all cases, the water that's released is perfectly adequate for growing microalgae. So let's envision what the system might look like. We call it OMEGA, which is an acronym for Offshore Membrane Enclosures for Growing Algae. At NASA, you have to have good acronyms.

So how does it work? I sort of showed you how it works already. We put waste water and some source of CO2 into our floating structure, and the waste water provides nutrients for the algae to grow, and they sequester CO2 that would otherwise go off into the atmosphere as a greenhouse gas. They of course use solar energy to grow, and the wave energy on the surface provides energy for mixing the algae, and the temperature is controlled by the surrounding water temperature. The algae that grow produce oxygen, as I've mentioned, and they also produce biofuels and fertilizer and food and other bi-algal products of interest.

And the system is contained. What do I mean by that? It's modular. Let's say something happens that's totally unexpected to one of the modules. It leaks. It's struck by lightning. The waste water that leaks out is water that already now goes into that coastal environment, and the algae that leak out are biodegradable, and because they're living in waste water, they're fresh water algae, which means they can't live in salt water, so they die. The plastic we'll build it out of is some kind of well-known plastic that we have good experience with, and we'll rebuild our modules to be able to reuse them again.

So we may be able to go beyond that when thinking about this system that I'm showing you, and that is to say we need to think in terms of the water, the fresh water, which is also going to be an issue in the future, and we're working on methods now for recovering the waste water.

The other thing to consider is the structure itself. It provides a surface for things in the ocean, and this surface, which is covered by seaweeds and other organisms in the ocean, will become enhanced marine habitat so it increases biodiversity. And finally, because it's an offshore structure, we can think in terms of how it might contribute to an aquaculture activity offshore.

So you're probably thinking, "Gee, this sounds like a good idea. What can we do to try to see if it's real?" Well, I set up laboratories in Santa Cruz at the California Fish and Game facility, and that facility allowed us to have big seawater tanks to test some of these ideas. We also set up experiments in San Francisco at one of the three waste water treatment plants, again a facility to test ideas. And finally, we wanted to see where we could look at what the impact of this structure would be in the marine environment, and we set up a field site at a place called Moss Landing Marine Lab in Monterey Bay, where we worked in a harbor to see what impact this would have on marine organisms.

The laboratory that we set up in Santa Cruz was our skunkworks. It was a place where we were growing algae and welding plastic and building tools and making a lot of mistakes, or, as Edison said, we were finding the 10,000 ways that the system wouldn't work. Now, we grew algae in waste water, and we built tools that allowed us to get into the lives of algae so that we could monitor the way they grow, what makes them happy, how do we make sure that we're going to have a culture that will survive and thrive. So the most important feature that we needed to develop were these so-called photobioreactors, or PBRs. These were the structures that would be floating at the surface made out of some inexpensive plastic material that'll allow the algae to grow, and we had built lots and lots of designs, most of which were horrible failures, and when we finally got to a design that worked, at about 30 gallons, we scaled it up to 450 gallons in San Francisco.

So let me show you how the system works. We basically take waste water with algae of our choice in it, and we circulate it through this floating structure, this tubular, flexible plastic structure, and it circulates through this thing, and there's sunlight of course, it's at the surface, and the algae grow on the nutrients.

But this is a bit like putting your head in a plastic bag. The algae are not going to suffocate because of CO2, as we would. They suffocate because they produce oxygen, and they don't really suffocate, but the oxygen that they produce is problematic, and they use up all the CO2. So the next thing we had to figure out was how we could remove the oxygen, which we did by building this column which circulated some of the water, and put back CO2, which we did by bubbling the system before we recirculated the water. And what you see here is the prototype, which was the first attempt at building this type of column. The larger column that we then installed in San Francisco in the installed system.

So the column actually had another very nice feature, and that is the algae settle in the column, and this allowed us to accumulate the algal biomass in a context where we could easily harvest it. So we would remove the algaes that concentrated in the bottom of this column, and then we could harvest that by a procedure where you float the algae to the surface and can skim it off with a net.

So we wanted to also investigate what would be the impact of this system in the marine environment, and I mentioned we set up this experiment at a field site in Moss Landing Marine Lab. Well, we found of course that this material became overgrown with algae, and we needed then to develop a cleaning procedure, and we also looked at how seabirds and marine mammals interacted, and in fact you see here a sea otter that found this incredibly interesting, and would periodically work its way across this little floating water bed, and we wanted to hire this guy or train him to be able to clean the surface of these things, but that's for the future.

Now really what we were doing, we were working in four areas. Our research covered the biology of the system, which included studying the way algae grew, but also what eats the algae, and what kills the algae. We did engineering to understand what we would need to be able to do to build this structure, not only on the small scale, but how we would build it on this enormous scale that will ultimately be required. I mentioned we looked at birds and marine mammals and looked at basically the environmental impact of the system, and finally we looked at the economics, and what I mean by economics is, what is the energy required to run the system? Do you get more energy out of the system than you have to put into the system to be able to make the system run? And what about operating costs? And what about capital costs? And what about, just, the whole economic structure?

So let me tell you that it's not going to be easy, and there's lots more work to do in all four of those areas to be able to really make the system work. But we don't have a lot of time, and I'd like to show you the artist's conception of how this system might look if we find ourselves in a protected bay somewhere in the world, and we have in the background in this image, the waste water treatment plant and a source of flue gas for the CO2, but when you do the economics of this system, you find that in fact it will be difficult to make it work. Unless you look at the system as a way to treat waste water, sequester carbon, and potentially for photovoltaic panels or wave energy or even wind energy, and if you start thinking in terms of integrating all of these different activities, you could also include in such a facility aquaculture. So we would have under this system a shellfish aquaculture where we're growing mussels or scallops. We'd be growing oysters and things that would be producing high value products and food, and this would be a market driver as we build the system to larger and larger scales so that it becomes, ultimately, competitive with the idea of doing it for fuels.

So there's always a big question that comes up, because plastic in the ocean has got a really bad reputation right now, and so we've been thinking cradle to cradle. What are we going to do with all this plastic that we're going to need to use in our marine environment? Well, I don't know if you know about this, but in California, there's a huge amount of plastic that's used in fields right now as plastic mulch, and this is plastic that's making these tiny little greenhouses right along the surface of the soil, and this provides warming the soil to increase the growing season, it allows us to control weeds, and, of course, it makes the watering much more efficient. So the OMEGA system will be part of this type of an outcome, and that when we're finished using it in the marine environment, we'll be using it, hopefully, on fields.

Where are we going to put this, and what will it look like offshore? Here's an image of what we could do in San Francisco Bay. San Francisco produces 65 million gallons a day of waste water. If we imagine a five-day retention time for this system, we'd need 325 million gallons to accomodate, and that would be about 1,280 acres of these OMEGA modules floating in San Francisco Bay. Well, that's less than one percent of the surface area of the bay. It would produce, at 2,000 gallons per acre per year, it would produce over 2 million gallons of fuel, which is about 20 percent of the biodiesel, or of the diesel that would be required in San Francisco, and that's without doing anything about efficiency.

Where else could we potentially put this system? There's lots of possibilities. There's, of course, San Francisco Bay, as I mentioned. San Diego Bay is another example, Mobile Bay or Chesapeake Bay, but the reality is, as sea level rises, there's going to be lots and lots of new opportunities to consider. (Laughter)

So what I'm telling you about is a system of integrated activities. Biofuels production is integrated with alternative energy is integrated with aquaculture.

I set out to find a pathway to innovative production of sustainable biofuels, and en route I discovered that what's really required for sustainability is integration more than innovation.

Long term, I have great faith in our collective and connected ingenuity. I think there is almost no limit to what we can accomplish if we are radically open and we don't care who gets the credit. Sustainable solutions for our future problems are going to be diverse and are going to be many. I think we need to consider everything, everything from alpha to OMEGA. Thank you. (Applause) (Applause) Chris Anderson: Just a quick question for you, Jonathan. Can this project continue to move forward within NASA or do you need some very ambitious green energy fund to come and take it by the throat? Jonathan Trent: So it's really gotten to a stage now in NASA where they would like to spin it out into something which would go offshore, and there are a lot of issues with doing it in the United States because of limited permitting issues and the time required to get permits to do things offshore. It really requires, at this point, people on the outside, and we're being radically open with this technology in which we're going to launch it out there for anybody and everybody who's interested to take it on and try to make it real. CA: So that's interesting. You're not patenting it. You're publishing it. JT: Absolutely. CA: All right. Thank you so much. JT: Thank you. (Applause)

数年前から バイオ燃料の開発にあたり ある可能性を追求してきました 化石燃料に対して競争力のある規模のものを 食糧生産に必要な水肥料や土地を奪わずに 開発できないかというものです

これがその解決案です 容器を作って海面下に浮かべ それを排水と 油分を生産する 微細藻類で満たす考えです 柔軟性のある素材で作るので 波の影響を受けて動きます もちろん微細藻類の成長には 太陽光を使い 藻類は二酸化炭素を吸収してくれながら 増殖し 酸素を放出します 微細藻類は周辺の水に熱を放出する 容器の中で増えるので これを収穫してバイオ燃料や化粧品 肥料や飼料として使えます 当然 培養には 広い面積を要するので 漁師や船舶等との利害関係も 考えなくてはいけませんが 将来の燃料事情を思うと 代替となる液体燃料を得ることが 大変重要であることは事実です

では なぜ微細藻類を使うのでしょうか? このグラフはバイオ燃料の生産に使える 様々なタイプの穀物を表しています 大豆は1ヘクタールあたり年間5百リットル程の バイオ燃料を生産できます 他にもヒマワリやカノーラジャトロファやヤシなど色々ありますが 一際高い値を示しているのが微細藻類です 大豆の年間5百リットルに比べて 微細藻類は1ヘクタールあたり 年間2万から5万リットル以上もの燃料を生産できます

では 微細藻類とは何でしょうか? マイクロ・スケールつまりとても小さい 単細胞生物でヒトの髪の毛と比べると この様に見えます この小さな生物は大昔から 何千もの種類が 生息しています 中には 地球上のどの植物よりも速く増え 先ほどお見せしたような多量の油分を生産するものもあります

ではなぜ このシステムを海上に作るのでしょうか 海上で行う大きな理由は 沿岸の都市を見ると分かるように他に良い場所がないからです 藻の栽培に排水を使うわけですが よく見てみると 排水処理場は 街の中に組み込まれています サンフランシスコの地下には 約1400Km に及ぶ下水管があり 沖に排水を放出しています 世界中 都市によって排水処理の仕方は違い 排水を浄化する都市もあれば 垂れ流しにする都市もあります しかしどの排水も 微細藻類の育成に使えます これはシステムの想像図です 「海上藻類養殖用膜質容器」の 頭文字を取ってOMEGAと名付けました NASAはこういう洒落た略語が好きなんです

どのように機能するのでしょうか? 先ほど少し説明しましたがまず 排水と二酸化炭素を 浮遊容器に入れます 排水が藻類の育成に必要な栄養を供給する一方 藻類は本来なら温室効果ガスとなるはずだった 二酸化炭素を吸収します もちろん 太陽のエネルギーも使って増殖し 海面の波のエネルギーが 藻類を撹拌しますまた 周りの水温によって 温度は制御されます この藻類が酸素を放出するのはすでに述べましたが バイオ燃料や肥料食料や藻独特の副産物など 有益なものも生み出します

このシステムは環境に害が広がらないよう設計されています モジュールとなって分かれているので 例えばその一つに雷が落ちたりして 穴が空き 中身が漏れたとしましょう 漏れ出す排水は 元来そのまま 排出されていた排水ですし 藻類は 漏れても自然分解されます 排水中で生育する藻類は 淡水生物なので海水の中では 生息できないのです ここで使用している プラスチックは よくあるもので 研究で良い成果を得ており 壊れたモジュールは修理して再利用できます

またこのシステムを使って もっと いろいろ出来るかもしれません 水 特に淡水については 将来 問題も予測されていますが 私たちは排水を再生する解決策にも 取り組んでいます

また 構造自体を考えると 海に生息するものの棲家になり 表面が海草や他の海洋生物で覆われ 優れた海洋生物の生息場と機能して 生物多様性を促進するのに 役立ちます 最後に 海中構造物なので 水産養殖という面からも 貢献できるのです

皆さんこう思うかもしれません 「良さそうなアイデアだけど本当に上手くいくのかな?」と 実はカリフォルニア州サンタクルーズにある 州の魚類鳥獣保護局内に研究室を設置し そこにある巨大な海水タンクで 試験実験を行っています またサンフランシスコに3つある 下水処理場のうちの1つでも 試験実験を行っています そしてこの構造物の 海洋環境への影響を調べるために モントレー湾にモスランディング海洋研究室という フィールド調査場を設置しました そこでこの構造物が海洋生物に どのような影響を与えるかを調べました

サンタクルーズの研究室がスカンクワークス(新技術開発の場)で そこで私たちは藻類を育て プラスチック溶接やツールを構築を行い たくさんの失敗を重ね エジソンではありませんが 「システムが機能しない10000もの方法」を学びました 現在は排水内で藻類を育ててますし 藻類の生態を調べるツールも構築したので 藻類の成長の様子や 藻類の好きな環境_そして 強く 繁殖力のある培養株の研究をしています さて 我々の開発した機能の中でも一番重要なのが フォトバイオリアクター(PBR)でした これは安価なプラスティック製の水面に浮かぶ構造物で 藻類類の養殖をする所ですいろいろなデザインを試し 殆どは失敗でしたが 113 リットルの規模で成功したモデルを 1700 リットル用に拡大してサンフランシスコに設置しました

システムがどう機能するかお見せしましょう 基本的に排水と好みの藻類を入れ そしてこの浮遊構造物の中を循環させます この管状の柔軟な プラスチック構造物です もちろん太陽光も外面に当たり 藻類は栄養を吸収し増殖します

でも これでは頭にビニール袋をかぶせたようなものです 藻類は人間と違って二酸化炭素による窒息死はしませんが 自ら生成する酸素によって窒息するのです 窒息とは ちょっと違いますが酸素は問題です また二酸化炭素も使い切ってしまいます なので次の問題は酸素を取り除くことで それをこのコラム(円柱)を立てて行いました コラムは一部の水を循環させ 水が戻る前に炭酸ガスの気泡を含ませ 二酸化炭素を戻します これはプロトタイプでこのタイプのコラムの最初の試みです サンフランシスコではより大きいコラムを システムに実装しています

このコラムには 実は他にも素晴らしい機能があって 増えた藻類がコラムに沈殿し 藻類バイオマスが集めやすくなるので 収穫が容易に行えるのです 私たちはコラムの下部にたまった藻類を取り除き それから表面に藻を浮かせて ネットでそれをすくい取る手順によって 簡単に収穫することができるのです

私たちは海洋環境へのこのシステムの影響も 調査したいと思っており お話ししたようにフィールド調査場を モスランディング海洋研究室に立ち上げました そこではこのシステムは外面が藻類に覆われてしまい 洗浄する仕組みが必要となりました また 海鳥や海の哺乳動物と どう影響しあうかも調べました このようにラッコも この構造物に非常に興味を示し 時々やってきては 浮かぶウォーターベッドの上を 横切っていきますなのでラッコを訓練し システム外面の清掃を 将来やってもらおうかと思ってます

ここでやってきた事は 4つの分野にまたがっています まずこのシステムの生物学的な研究では 藻類の成長についてだけでなく 何が藻類を食べたり 殺したりするかも調べました エンジニアリングの分野では 構造物を作るために何が必要か 小規模にとどまらず いずれ求められる 大規模なシステム構築も合わせて考えてきました また鳥や海洋哺乳類のお話もしましたが このシステムの環境への影響も調べました そして更に経済にも目を向けています ここで言う経済とは このシステム稼働にどのくらいエネルギーが必要か? 稼働を続けるために 投入したエネルギー以上を システムから得られるかということです 運用コストはどうか 資本にどれだけコストがかかるか それから全体の経済構造はどうかなどです

はっきり言ってこれは難しい問題です 実際システムを作るには 4つの分野すべてに課題がたくさん残っています 今日は時間がありませんので このシステムの完成イメージをお見せしましょう 世界どこかにある静かな入り江に作るとこうなります イメージ後方には 排水処理施設や 二酸化炭素排出源が見えます でも経済的なことを考えると これだけでは難しいことが分かります このシステムを排水処理や炭素隔離の 手段と考えたり太陽電池パネルや 波エネルギー 風力エネルギーといった このような様々なものと 統合していく必要があります 水産養殖を加えることもできます システムの下で貝の養殖を行い ムラサキガイかホタテを育てたり カキなど 高値な食品を 生産する事も考えられます これらをシステムの牽引力として 次第に規模を拡大すれば 究極的に競争力のある燃料源とすることが出来るかもしれません

ここで必ず疑問となるのが 最近の海を漂うプラスチックの問題です そこで「ゆりかごからゆりかごへ」(資源の再利用)を考えています 私たちが海洋環境で必要とする 大量のプラスチックをどうするかが問題です ご存じかもしれませんがカリフォルニアでは 膨大な量のプラスチック・シートが耕地の表面を覆うために使われています これらは土壌表層の上で 小さな温室の役目をし 土壌を暖め植物の生長を促します また雑草を抑制し 水の利用効果を高めます OMEGAシステムも同種の評価を得られ また海洋環境で使用済みのプラスチックを 農地で使えたりしたら良いと思っています

ではシステムが設置されると どの様な景色になるでしょうか? これはサンフランシスコ湾でのイメージです サンフランシスコの排水は1日あたり2.4億リットルです 5日分を貯めて使うシステムは 12億リットルの容量が必要になります それには518ヘクタールのOMEGAモジュールを サンフランシスコ湾に浮かべることになります これは湾全体の表面積の1%以下にあたります このシステムは1ヘクタールで年間1.87万リットル生産するので 全体での総量は750万リットル以上になり サンフランシスコで必要とされるディーゼルの20%分が生産できます 効率性に何も工夫を加えなかったとしてもです

では他の場所ではどうでしょう? 多くの場所が考えられます もちろんサンフランシスコ湾は可能ですし 他ではサンディエゴ湾 モバイル湾やチェスピーク湾などもいいですね 海面が上るにつれ 新しい候補は増えますね(笑)

大切なのは このシステムは 複数の活動を統合したシステムだということです バイオ燃料の生産は代替エネルギーと統合され また それが水産養殖とも統合されているわけです

私は持続可能なバイオ燃料の 革新的な生産の方法を探求していたのですが その過程で サステナビリティ(持続可能性)に必要なのは イノベーションではなく統合である事に気が付きました

長い目でものを見るとき集団としての力や つながりによる創造性を信じています もし私たちが基本的にオープンであり 誰に名誉が行くかなどに こだわらなければ そこには無限の可能性があると思います 将来の問題に対する持続可能なソリューションは いろいろな形で 多数存在すると思います 全ての可能性を考えることが必要です 全て つまりアルファからOMEGAまでです ありがとうございました(拍手) (拍手) 簡単な質問があります ジョナサン プロジェクトはNASA内部で続けられるのですか? それとも野心的なグリーンエネルギーファンドなどが 続けていくには必要なのですか? NASAではそろそろ独立させ 海上にプロジェクトを広げる段階に 来ていますが アメリカ国内でやるには問題がたくさんあります 海上での展開には様々な制限があり 許可収得にも時間がかかります 現段階で 外部の協力が必要です 私たちはこの技術を 誰にでもオープンにしていますので 興味がある方に実現して欲しいとも思ってます 面白いですね 特許を得るのではなく技術を広めたいと そのとおりです 分かりました ありがとうございました こちらこそ(拍手)

品詞分類

- 主語

- 動詞

- 助動詞

- 準動詞

- 関係詞等

TED 日本語

TED Talks

関連動画

印刷できる柔軟な有機太陽電池ハナ・ブルクシュトゥマ

2018.05.08

気候変動の解消に向けた原子力発電の必要性ジョー・ラシター

2016.12.19

同期したハンマーの一撃が核融合を成功に導くマイケル・ラバーグ

2014.04.22

行動科学で電気代が安くなるわけアレックス・ラスキー

2013.06.04

僕のラジカルな計画―小型核分裂炉で世界を変えるテイラー・ウィルソン

2013.04.30

再生可能エネルギーの現実デイビッド・マッケイ

2012.05.25

エネルギーの40ヶ年計画エイモリー・ロビンス

2012.05.01

再生可能エネルギーを本当に使えるようにするにはドナルド・サドウェイ

2012.03.26

うん、核融合炉を作ったよテイラー・ウィルソン

2012.03.22

天然ガスでエネルギーを変革しようT.ブーン・ピケンズ

2012.03.19

送電網を必要としないエネルギーをジャスティン・ホール・ティピング

2011.10.18

「脱石油」について語るリチャード・シアーズ

2010.05.20

未来エネルギーの核融合スティーヴン・カウリー

2009.12.22

未来の再生可能エネルギーとしての凧ソール・グリフィス

2009.03.22

洋楽 おすすめ

RECOMMENDS

洋楽歌詞

ダイナマイトビーティーエス

洋楽最新ヒット2020.08.20

ディス・イズ・ミーグレイテスト・ショーマン・キャスト

洋楽人気動画2018.01.11

グッド・ライフGイージー、ケラーニ

洋楽人気動画2017.01.27

ホワット・ドゥ・ユー・ミーン?ジャスティン・ビーバー

洋楽人気動画2015.08.28

ファイト・ソングレイチェル・プラッテン

洋楽人気動画2015.05.19

ラヴ・ミー・ライク・ユー・ドゥエリー・ゴールディング

洋楽人気動画2015.01.22

アップタウン・ファンクブルーノ・マーズ、マーク・ロンソン

洋楽人気動画2014.11.20

ブレイク・フリーアリアナ・グランデ

洋楽人気動画2014.08.12

ハッピーファレル・ウィリアムス

ポップス2014.01.08

カウンティング・スターズワンリパブリック

ロック2013.05.31

ア・サウザンド・イヤーズクリスティーナ・ペリー

洋楽人気動画2011.10.26

ユー・レイズ・ミー・アップケルティック・ウーマン

洋楽人気動画2008.05.30

ルーズ・ユアセルフエミネム

洋楽人気動画2008.02.21

ドント・ノー・ホワイノラ・ジョーンズ

洋楽人気動画2008.02.15

オンリー・タイムエンヤ

洋楽人気動画2007.10.03

ミス・ア・シングエアロスミス

ロック2007.08.18

タイム・トゥ・セイ・グッバイサラ・ブライトマン

洋楽人気動画2007.06.08

シェイプ・オブ・マイ・ハートスティング

洋楽人気動画2007.03.18

ウィ・アー・ザ・ワールド(U.S.A. フォー・アフリカ)マイケル・ジャクソン

洋楽人気動画2006.05.14

ホテル・カリフォルニアイーグルス

ロック2005.07.06