TED日本語

TED Talks(英語 日本語字幕付き動画)

TED日本語 - ドナルド・サドウェイ: 再生可能エネルギーを本当に使えるようにするには

TED Talks

再生可能エネルギーを本当に使えるようにするには

The missing link to renewable energy

ドナルド・サドウェイ

Donald Sadoway

内容

太陽光や風力などの代替エネルギーを使うための鍵となる秘策はなんでしょう?それは蓄電池なのです。蓄電池があれば太陽が出ていなくても風が吹かなくても、電力を得ることができます。このとっつきやすくてひらめきを与えるようなトークでは、ドナルド・サドウェイが黒板を使って再生可能エネルギー用の巨大な電池の未来を説明します。そして彼は説くのです、「問題に対して今までとは異なる考え方が必要です。大きく、そして、安く考えるのです」と。

字幕

SCRIPT

Script

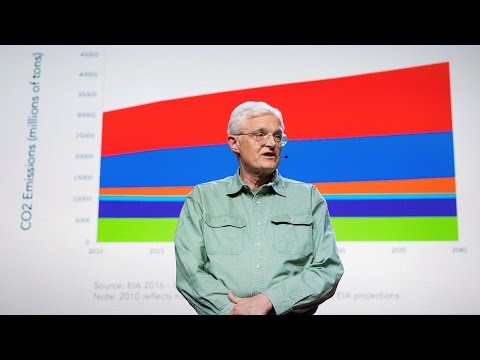

The electricity powering the lights in this theater was generated just moments ago. Because the way things stand today, electricity demand must be in constant balance with electricity supply. If in the time that it took me to walk out here on this stage, some tens of megawatts of wind power stopped pouring into the grid, the difference would have to be made up from other generators immediately. But coal plants, nuclear plants can't respond fast enough. A giant battery could. With a giant battery, we'd be able to address the problem of intermittency that prevents wind and solar from contributing to the grid in the same way that coal, gas and nuclear do today.

You see, the battery is the key enabling device here. With it, we could draw electricity from the sun even when the sun doesn't shine. And that changes everything. Because then renewables such as wind and solar come out from the wings, here to center stage. Today I want to tell you about such a device. It's called the liquid metal battery. It's a new form of energy storage that I invented at MIT along with a team of my students and post-docs.

Now the theme of this year's TED Conference is Full Spectrum. The OED defines spectrum as "The entire range of wavelengths of electromagnetic radiation, from the longest radio waves to the shortest gamma rays of which the range of visible light is only a small part." So I'm not here today only to tell you how my team at MIT has drawn out of nature a solution to one of the world's great problems. I want to go full spectrum and tell you how, in the process of developing this new technology, we've uncovered some surprising heterodoxies that can serve as lessons for innovation, ideas worth spreading. And you know, if we're going to get this country out of its current energy situation, we can't just conserve our way out; we can't just drill our way out; we can't bomb our way out. We're going to do it the old-fashioned American way, we're going to invent our way out, working together.

(Applause)

Now let's get started. The battery was invented about 200 years ago by a professor, Alessandro Volta, at the University of Padua in Italy. His invention gave birth to a new field of science, electrochemistry, and new technologies such as electroplating. Perhaps overlooked, Volta's invention of the battery for the first time also demonstrated the utility of a professor. (Laughter) Until Volta, nobody could imagine a professor could be of any use.

Here's the first battery -- a stack of coins, zinc and silver, separated by cardboard soaked in brine. This is the starting point for designing a battery -- two electrodes, in this case metals of different composition, and an electrolyte, in this case salt dissolved in water. The science is that simple. Admittedly, I've left out a few details.

Now I've taught you that battery science is straightforward and the need for grid-level storage is compelling, but the fact is that today there is simply no battery technology capable of meeting the demanding performance requirements of the grid -- namely uncommonly high power, long service lifetime and super-low cost. We need to think about the problem differently. We need to think big, we need to think cheap.

So let's abandon the paradigm of let's search for the coolest chemistry and then hopefully we'll chase down the cost curve by just making lots and lots of product. Instead, let's invent to the price point of the electricity market. So that means that certain parts of the periodic table are axiomatically off-limits. This battery needs to be made out of earth-abundant elements. I say, if you want to make something dirt cheap, make it out of dirt -- (Laughter) preferably dirt that's locally sourced. And we need to be able to build this thing using simple manufacturing techniques and factories that don't cost us a fortune.

So about six years ago, I started thinking about this problem. And in order to adopt a fresh perspective, I sought inspiration from beyond the field of electricity storage. In fact, I looked to a technology that neither stores nor generates electricity, but instead consumes electricity, huge amounts of it. I'm talking about the production of aluminum. The process was invented in 1886 by a couple of 22-year-olds -- Hall in the United States and Heroult in France. And just a few short years following their discovery, aluminum changed from a precious metal costing as much as silver to a common structural material.

You're looking at the cell house of a modern aluminum smelter. It's about 50 feet wide and recedes about half a mile -- row after row of cells that, inside, resemble Volta's battery, with three important differences. Volta's battery works at room temperature. It's fitted with solid electrodes and an electrolyte that's a solution of salt and water. The Hall-Heroult cell operates at high temperature, a temperature high enough that the aluminum metal product is liquid. The electrolyte is not a solution of salt and water, but rather salt that's melted. It's this combination of liquid metal, molten salt and high temperature that allows us to send high current through this thing. Today, we can produce virgin metal from ore at a cost of less than 50 cents a pound. That's the economic miracle of modern electrometallurgy.

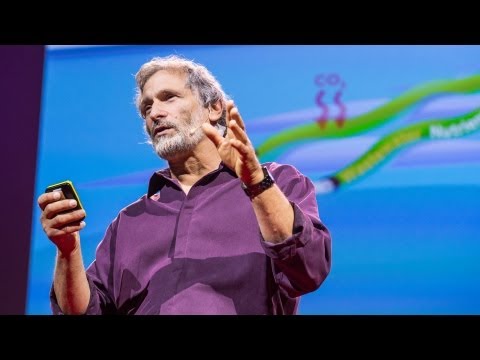

It is this that caught and held my attention to the point that I became obsessed with inventing a battery that could capture this gigantic economy of scale. And I did. I made the battery all liquid -- liquid metals for both electrodes and a molten salt for the electrolyte. I'll show you how. So I put low-density liquid metal at the top, put a high-density liquid metal at the bottom, and molten salt in between.

So now, how to choose the metals? For me, the design exercise always begins here with the periodic table, enunciated by another professor, Dimitri Mendeleyev. Everything we know is made of some combination of what you see depicted here. And that includes our own bodies. I recall the very moment one day when I was searching for a pair of metals that would meet the constraints of earth abundance, different, opposite density and high mutual reactivity. I felt the thrill of realization when I knew I'd come upon the answer. Magnesium for the top layer. And antimony for the bottom layer. You know, I've got to tell you,one of the greatest benefits of being a professor: colored chalk.

(Laughter)

So to produce current, magnesium loses two electrons to become magnesium ion, which then migrates across the electrolyte, accepts two electrons from the antimony, and then mixes with it to form an alloy. The electrons go to work in the real world out here, powering our devices. Now to charge the battery, we connect a source of electricity. It could be something like a wind farm. And then we reverse the current. And this forces magnesium to de-alloy and return to the upper electrode, restoring the initial constitution of the battery. And the current passing between the electrodes generates enough heat to keep it at temperature.

It's pretty cool, at least in theory. But does it really work? So what to do next? We go to the laboratory. Now do I hire seasoned professionals? No, I hire a student and mentor him, teach him how to think about the problem, to see it from my perspective and then turn him loose. This is that student, David Bradwell, who, in this image, appears to be wondering if this thing will ever work. What I didn't tell David at the time was I myself wasn't convinced it would work.

But David's young and he's smart and he wants a Ph.D., and he proceeds to build -- (Laughter) He proceeds to build the first ever liquid metal battery of this chemistry. And based on David's initial promising results, which were paid with seed funds at MIT, I was able to attract major research funding from the private sector and the federal government. And that allowed me to expand my group to 20 people, a mix of graduate students, post-docs and even some undergraduates.

And I was able to attract really, really good people, people who share my passion for science and service to society, not science and service for career building. And if you ask these people why they work on liquid metal battery, their answer would hearken back to President Kennedy's remarks at Rice University in 1962 when he said -- and I'm taking liberties here -- "We choose to work on grid-level storage, not because it is easy, but because it is hard."

(Applause)

So this is the evolution of the liquid metal battery. We start here with our workhorse one watt-hour cell. I called it the shotglass. We've operated over 400 of these, perfecting their performance with a plurality of chemistries -- not just magnesium and antimony. Along the way we scaled up to the 20 watt-hour cell. I call it the hockey puck. And we got the same remarkable results. And then it was onto the saucer. That's 200 watt-hours. The technology was proving itself to be robust and scalable. But the pace wasn't fast enough for us. So a year and a half ago, David and I, along with another research staff-member, formed a company to accelerate the rate of progress and the race to manufacture product.

So today at LMBC, we're building cells 16 inches in diameter with a capacity of one kilowatt-hour -- 1,000 times the capacity of that initial shotglass cell. We call that the pizza. And then we've got a four kilowatt-hour cell on the horizon. It's going to be 36 inches in diameter. We call that the bistro table, but it's not ready yet for prime-time viewing. And one variant of the technology has us stacking these bistro tabletops into modules, aggregating the modules into a giant battery that fits in a 40-foot shipping container for placement in the field. And this has a nameplate capacity of two megawatt-hours -- two million watt-hours. That's enough energy to meet the daily electrical needs of 200 American households. So here you have it, grid-level storage: silent, emissions-free, no moving parts, remotely controlled, designed to the market price point without subsidy.

So what have we learned from all this?

(Applause) So what have we learned from all this? Let me share with you some of the surprises, the heterodoxies. They lie beyond the visible. Temperature: Conventional wisdom says set it low, at or near room temperature, and then install a control system to keep it there. Avoid thermal runaway. Liquid metal battery is designed to operate at elevated temperature with minimum regulation. Our battery can handle the very high temperature rises that come from current surges. Scaling: Conventional wisdom says reduce cost by producing many. Liquid metal battery is designed to reduce cost by producing fewer, but they'll be larger. And finally, human resources: Conventional wisdom says hire battery experts, seasoned professionals, who can draw upon their vast experience and knowledge. To develop liquid metal battery, I hired students and post-docs and mentored them. In a battery, I strive to maximize electrical potential; when mentoring, I strive to maximize human potential. So you see, the liquid metal battery story is more than an account of inventing technology, it's a blueprint for inventing inventors, full-spectrum.

(Applause)

この会場を照らす光の電力は 一瞬前に発電されたものです 今日では 電気の需要に対して供給を合わせるということが 絶え間なく続いているのです 私がこのステージに上がったときも もし 数10メガワットの風力発電からの電力が グリッドに流れなくなったとしたら 直ちに他の発電機から 代替される必要がでてくるでしょう しかし火力発電や原子力発電だと時間が掛かりすぎ 即座に代替発電ができません 巨大畜電池ならできるでしょう 大容量の畜電池があれば 風力発電や太陽光発電をグリッドに組み込むのに 障害となっている 間欠性の問題を解決することができ それらの発電を今日の火力や原子力と同様に使えるかもしれません

わかりますよね ここでは畜電池が鍵となっています 畜電池があれば曇った時でさえも太陽から 電気を引き出すことができます そうすれば世界が変わります なぜなら風や太陽光といった 再生可能エネルギーが 自然界の脇役から 風に乗って 主役に踊りでるのです 今日はそのような機器について話します 液体金属電池と呼んでいるものです これは新しいタイプの エネルギー貯蔵媒体で MITの学生・ポスドクチームと一緒に 発明しました

さてTED2012のテーマはフルスペクトルです オックスフォード英英辞典によれば スペクトルとは 「電磁波のあらゆる波長― 超低周波から最長のガンマ線まであり 目に見えるのはごく僅かである」と 定義しています ですから このTEDでは単に MITでの私のチームが自然に辿りついた 世界的問題の1つへの解決策だけを話すのではなく フルスペクトルの如く様々な話をしたいです この新技術を開発する中で 私たちがどのようにして 驚くような異説を発見したかについてです それはイノベーションのための教訓であり 広める価値のあるアイデアです ご存じの通り 近日のエネルギー問題からアメリカを救おうとするなら 単なる節約なんかではいけません 新たな石油採掘に頼ることもできません 爆破すればいいわけでもないのです 古典的なアメリカ流の方法 つまり 発明に道を見い出して 問題解決に協同で励むのです

(拍手)

では始めましょうか 電池というものは約200年前 イタリアのパヴィア大学教授 アレッサンドロ・ボルタが発明しました これによって 新たな科学分野である電気化学や 電気めっきなどの 新技術が生まれました 見落としがちですが ボルタの発明は同時に 世界で初めて 教授の有用性を示したのです (笑) それまでは教師が役に立つなんて 想像する人すらいませんでした

これが世界初の電池です 硬貨形の亜鉛と銀が山積みにされ 塩水漬けのボール紙により 分けられています これが電池設計の 始まりだったのです 2つの電極と電解液― この場合は 異なる組成の金属と塩水が それらを担っていました 科学はそれほどシンプルなのです 明らかに 私は詳しい話をいくつか省きました

私がお教えしたように 電池の科学はシンプルで 送電網における電気貯蔵が 切実に求められています しかし実際はというと 現在 グリッドが必要とするパフォーマンス特性― すなわち 通常よりも高出力で 寿命も長く そしてコストも激安という要件を 全て満たすことのできる 電池の技術など 単純に存在しないのです この問題を違う視点で考える必要があるのです 大きく考え そして 安くできる方法を考えるのです

従来の考えを捨て 最も斬新な コンビを探しましょう そして大量の製品を 作ることによって うまくいけば コスト削減できるでしょう 運に任せずに 電力市場が 買う気になる価格のものを発明をするのです つまり 周期表の― 高くつく種々の部分は 明らかに対象外とすることを意味します 電池は地球に豊富な資源で 作られる必要があります 私ならこう言います 格安に作りたいなら そこらにある土を使えとね (笑) 好ましいのは 地元の土を原料にすることです(笑) 私たちはこういった製品を作るのに 莫大な費用がかからない シンプルな製造技術と工場を使う必要があります

6年ほど前に この問題について考え始めました そして新たな視点を養うため 電気貯蔵以外の分野からのインスピレーションを求めました 実のところ 私が注目したのは 電気を貯めたり発電したりする技術ではなく 電気を消費する技術で しかも大量に消費する技術でした そう これはアルミニウムの製造の話です 製造過程は1886年 二人の22歳の若者 アメリカのホールとフランスのエルーが発明しました その発見のほんの数年後 アルミニウムは 銀と同じ価値の貴金属という存在から 平凡な建築材料へとなりました

今見えているのはアルミニウム精錬所の中です 15メートルの幅と 800メートルの奥行きがあり ボルタ電池に似た 小さなコンテナがずらりと並んでいます 重要な違いが3つあります ボルタ電池は室温で動作し 固体電極と塩水の電解液から できています ホール・エルーの電解炉セルは アルミニウム金属生成物が 融解するのに十分な高温の中で 動作しています 電解質は 塩と水の溶液ではなく むしろ融解塩です つまり 液体金属と融解塩と 高温な状態の組み合わせこそが 大電流を流すことを可能にします 現代では 鉱石からアルミニウムを生産するのに 1キロ当たり1ドル弱のコストでできます これは現代の電気冶金における 経済的な奇跡です

この奇跡こそがきっかけとなって 私は 経済的に 莫大な規模の経済性を追求できるような 電池の発明に夢中になりました そしてやりとげたのです 両極用の液体金属と 電解質の融解塩から成る 完全な液体電池を作ったのです どのように反応するのかお話します まず低密度の液体金属を 一番上に置きます 高密度の液体金属は一番下で その間に融解塩を置きます

さてさて 次は使う金属をどうやって選びましょうか? 私の場合 設計する際はいつも ドミトリ・メンデレーエフが作った 周期表を使って 始めるのです 私たちが知るすべてのものは この周期表にある原子の 様々な組み合わせによってできています 人間の体も例外ではないです 私は当時 地球に豊富な資源で 密度は異なるが相互反応が高いという これら全ての制約を満たす 両極用の金属を探していました その時に起こったあの瞬間のことを 覚えています その答えを得たと悟ったとき 私はその実感に震えました 最上層部にマグネシウム そして最下層部に アンチモンの組み合わせです 話さずにはいれないことがあります 教授であることの素敵な恩恵の1つは 多色のチョークで表現できることです

(笑)

電流を発生させるために マグネシウムは電子を2個失って マグネシウムイオンへと変化します それは電解質中を動き回り アンチモンから電子を2個吸収した後 混ざり合って結合状態が形成されます ここで発生した電子は この現実世界で 機器に電力を供給するという役割を 担っているのです また 電池を充電するためには 電力の発生源に接続します ここでは風力発電としましょう そして逆方向に電流を流します この流れを受けると マグネシウムは強制的に 結合を解除して上部電極に戻り 元の構成を復元するのです 電極間を通る電流は 適温を保つのに適度な熱を生み出します

少なくとも概念的には かっこいいですよね しかし実現できるでしょうか? 次はどうすればいいのでしょう? ここからは実験室での話です ベテランの専門家を雇うのかって? いえいえ 私は学生を雇って 彼のメンターとなり 私の視点から問題を捉えられるよう 指導した後 彼自身が考えるようにしました これがその学生 デビッドです この写真での彼の顔は 試作が成功するかを心配しているようです この時には言いませんでしたが うまくいくか確信はありませんでした

しかしデビットは若く賢くて 彼は博士号が欲しかったのです だから試作を始めました (笑) 彼は先の組み合わせに基づく 史上初の液体金属電池を 作り始めました 彼の最初の研究結果は有望でした この初期研究費用は MITの起業助成で賄いました 有望な結果が基となって 私は民間企業や連邦政府からの 多額な研究資金を 引きつけることができました これによって研究チームは20人にまで増やすことができ 院生やポスドクのほか 学部生さえもチームにいました

いい人たちばかりを集めることができました 私の科学と社会貢献への情熱を 共有してくれる人たちです 決して キャリア形成の手段として科学や研究を行う人たちではありません 液体金属電池を研究する理由を チームに聞くと その回答は 1962年ライス大学で ケネディ大統領が述べた言葉を 思い出させます 勝手に少し変更して言いますが 「この電池を研究するのは それが簡単だからではない それが困難だからだ」

(喝采)

次に 液体金属電池の進化過程をお話しします 熱心な仲間と共に 最初は矢印の1Wh 電池から始めました これを「ショットグラス」と呼んでいます 私たちは これを400個以上試作して マグネシウムとアンチモン以外にもある複数の化学反応に ミスがでないようにしました 徐々に出力を上げていき 20Wh の電力に到達しました 「ホッケーパック」と呼んでいます これでも同様に優れた結果がでました さらに大型の「ソーサー」へと作り進み 今度は200Whです この技術は頑丈で 同じ条件で大規模化が可能だと証明されました しかし開発速度が十分ではなかったのです 1年半前に デビッドと私は 他のメンバーを引き連れて 会社を立ち上げました そこで製品化までの時間を 早めようとしました

さてLMBC(液体金属電池社)では 現在 直径40センチのセルを 作っていますが 最大容量は当初の「ショットグラス」型の1000倍の 1kWhもあります これを「ピザ」と呼んでいます 近い将来 4kWhのセルができるでしょう 直径は91センチ強になる予定です 名前は「ビストロテーブル」ですが ゴールデンタイム放送にはまだ早いです この技術の改良品が 「ビストロテーブル」を何個も積み重ねてモジュール化し そのモジュールを集約して巨大な電池としたものです これを搬送する場合には 12メートル輸送コンテナにいれます 最大容量は2メガWh つまり 200万Whもあります これはアメリカ家庭200世帯分の 日々の電力需要を満たすのに 十分なエネルギーです さあここにグリッドに組み込める貯蔵電池があります 静かで 排出ガスもなく 動く部品もありません 遠隔操作もでき 助成金なしでも 市場で通じる価格になるように 設計されています

ここから何が学べたでしょう?

(拍手) ここから何が学べたでしょう? ではいくつかの驚きと 通説と異なっていた視点を共有しようと思います 目では見られないことです 温度について― 世間一般の概念通りにすれば 室温か それに近い低温に設定し それから制御装置を設置して温度を保ちます 熱逸走を防ぐためです 液体金属電池は温度上昇時でも 最低限の温度調整で作動するよう設計されています この電池は電流急増による 温度の急上昇にも対処できるのです 拡張性について― 世間一般の概念での価格戦略とは 大量生産でコストを減らすことです 液体金属電池の場合 単純化し部品数を減らすことで コストを減らす一方 拡張していくこともできます 最後に人的資源について― 世間一般の概念では 豊富な経験と知識を 活用できるよう 電池の専門家や熟練者を雇えと言っています 今回の場合 大学生と院生を雇って彼らを指導したのです 私は電池の潜在能力を 最大限に引き出そうと努めました 同様に 彼らを指導するときは 彼らの潜在能力を引き出そうと努めました わかりますよね この液体金属電池の話は 新技術発明の 単なる報告ではないです 発明者を発明する青写真でもあるのです これこそフルスペクトルですよね

(拍手)

品詞分類

- 主語

- 動詞

- 助動詞

- 準動詞

- 関係詞等

TED 日本語

TED Talks

関連動画

印刷できる柔軟な有機太陽電池ハナ・ブルクシュトゥマ

2018.05.08

気候変動の解消に向けた原子力発電の必要性ジョー・ラシター

2016.12.19

同期したハンマーの一撃が核融合を成功に導くマイケル・ラバーグ

2014.04.22

行動科学で電気代が安くなるわけアレックス・ラスキー

2013.06.04

僕のラジカルな計画―小型核分裂炉で世界を変えるテイラー・ウィルソン

2013.04.30

次世代バイオ燃料生産、海に浮かべる藻のゆりかごジョナサン・トレント

2012.09.08

再生可能エネルギーの現実デイビッド・マッケイ

2012.05.25

エネルギーの40ヶ年計画エイモリー・ロビンス

2012.05.01

うん、核融合炉を作ったよテイラー・ウィルソン

2012.03.22

天然ガスでエネルギーを変革しようT.ブーン・ピケンズ

2012.03.19

送電網を必要としないエネルギーをジャスティン・ホール・ティピング

2011.10.18

「脱石油」について語るリチャード・シアーズ

2010.05.20

未来エネルギーの核融合スティーヴン・カウリー

2009.12.22

未来の再生可能エネルギーとしての凧ソール・グリフィス

2009.03.22

洋楽 おすすめ

RECOMMENDS

洋楽歌詞

ダイナマイトビーティーエス

洋楽最新ヒット2020.08.20

ディス・イズ・ミーグレイテスト・ショーマン・キャスト

洋楽人気動画2018.01.11

グッド・ライフGイージー、ケラーニ

洋楽人気動画2017.01.27

ホワット・ドゥ・ユー・ミーン?ジャスティン・ビーバー

洋楽人気動画2015.08.28

ファイト・ソングレイチェル・プラッテン

洋楽人気動画2015.05.19

ラヴ・ミー・ライク・ユー・ドゥエリー・ゴールディング

洋楽人気動画2015.01.22

アップタウン・ファンクブルーノ・マーズ、マーク・ロンソン

洋楽人気動画2014.11.20

ブレイク・フリーアリアナ・グランデ

洋楽人気動画2014.08.12

ハッピーファレル・ウィリアムス

ポップス2014.01.08

カウンティング・スターズワンリパブリック

ロック2013.05.31

ア・サウザンド・イヤーズクリスティーナ・ペリー

洋楽人気動画2011.10.26

ユー・レイズ・ミー・アップケルティック・ウーマン

洋楽人気動画2008.05.30

ルーズ・ユアセルフエミネム

洋楽人気動画2008.02.21

ドント・ノー・ホワイノラ・ジョーンズ

洋楽人気動画2008.02.15

オンリー・タイムエンヤ

洋楽人気動画2007.10.03

ミス・ア・シングエアロスミス

ロック2007.08.18

タイム・トゥ・セイ・グッバイサラ・ブライトマン

洋楽人気動画2007.06.08

シェイプ・オブ・マイ・ハートスティング

洋楽人気動画2007.03.18

ウィ・アー・ザ・ワールド(U.S.A. フォー・アフリカ)マイケル・ジャクソン

洋楽人気動画2006.05.14

ホテル・カリフォルニアイーグルス

ロック2005.07.06