TED日本語

TED Talks(英語 日本語字幕付き動画)

TED日本語 - デビッド・バーン: いかにして建築が音楽を進化させたか

TED Talks

いかにして建築が音楽を進化させたか

How architecture helped music evolve

デビッド・バーン

David Byrne

内容

CBGBからカーネギー・ホールまで― キャリアの広がりにつれデビッド・バーンはさまざまな場所で演奏してきました。会場が音楽を作るのでしょうか?野外ドラムからワグナーオペラ、アリーナロックまで、いかに音楽のおかれた環境が音楽自体を進化させていったかを探っていきます。

字幕

SCRIPT

Script

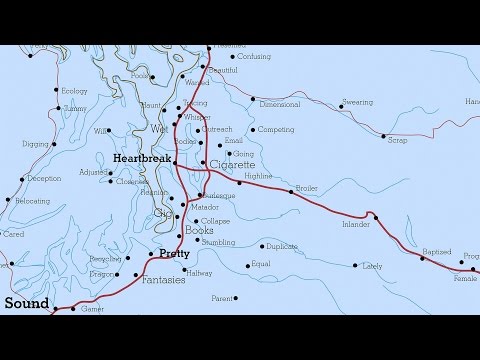

This is the venue where, as a young man, some of the music that I wrote was first performed. It was, remarkably, a pretty good sounding room. With all the uneven walls and all the crap everywhere, it actually sounded pretty good. This is a song that was recorded there. (Music) This is not Talking Heads, in the picture anyway. (Music: "A Clean Break (Let's Work)" by Talking Heads) So the nature of the room meant that words could be understood. The lyrics of the songs could be pretty much understood. The sound system was kind of decent. And there wasn't a lot of reverberation in the room. So the rhythms could be pretty intact too, pretty concise. Other places around the country had similar rooms. This is Tootsie's Orchid Lounge in Nashville. The music was in some ways different, but in structure and form, very much the same. The clientele behavior was very much the same too. And so the bands at Tootsie's or at CBGB's had to play loud enough -- the volume had to be loud enough to overcome people falling down, shouting out and doing whatever else they were doing.

Since then, I've played other places that are much nicer. I've played the Disney Hall here and Carnegie Hall and places like that. And it's been very exciting. But I also noticed that sometimes the music that I had written, or was writing at the time, didn't sound all that great in some of those halls. We managed, but sometimes those halls didn't seem exactly suited to the music I was making or had made. So I asked myself: Do I write stuff for specific rooms? Do I have a place, a venue, in mind when I write? Is that a kind of model for creativity? Do we all make things with a venue, a context, in mind?

Okay, Africa. (Music: "Wenlenga" / Various artists) Most of the popular music that we know now has a big part of its roots in West Africa. And the music there, I would say, the instruments, the intricate rhythms, the way it's played, the setting, the context, it's all perfect. It all works perfect. The music works perfectly in that setting. There's no big room to create reverberation and confuse the rhythms. The instruments are loud enough that they can be heard without amplification, etc., etc. It's no accident. It's perfect for that particular context. And it would be a mess in a context like this. This is a gothic cathedral. (Music: "Spem In Alium" by Thomas Tallis) In a gothic cathedral, this kind of music is perfect. It doesn't change key, the notes are long, there's almost no rhythm whatsoever, and the room flatters the music. It actually improves it. This is the room that Bach wrote some of his music for. This is the organ. It's not as big as a gothic cathedral, so he can write things that are a little bit more intricate. He can, very innovatively, actually change keys without risking huge dissonances. (Music: "Fantasia On Jesu, Mein Freunde" by Johann S. Bach)

This is a little bit later. This is the kind of rooms that Mozart wrote in. I think we're in like 1770, somewhere around there. They're smaller, even less reverberant, so he can write really frilly music that's very intricate -- and it works. (Music: "Sonata in F," KV 13, by Wolfgang A. Mozart) It fits the room perfectly. This is La Scala. It's around the same time, I think it was built around 1776. People in the audience in these opera houses, when they were built, they used to yell out to one another. They used to eat, drink and yell out to people on the stage, just like they do at CBGB's and places like that. If they liked an aria, they would holler and suggest that it be done again as an encore, not at the end of the show, but immediately. (Laughter) And well, that was an opera experience. This is the opera house that Wagner built for himself. And the size of the room is not that big. It's smaller than this. But Wagner made an innovation. He wanted a bigger band. He wanted a little more bombast, so he increased the size of the orchestra pit so he could get more low-end instruments in there. (Music: "Lohengrin / Prelude to Act III" by Richard Wagner)

Okay. This is Carnegie Hall. Obviously, this kind of thing became popular. The halls got bigger. Carnegie Hall's fair-sized. It's larger than some of the other symphony halls. And they're a lot more reverberant than La Scala. Around the same, according to Alex Ross who writes for the New Yorker, this kind of rule came into effect that audiences had to be quiet -- no more eating, drinking and yelling at the stage, or gossiping with one another during the show. They had to be very quiet. So those two things combined meant that a different kind of music worked best in these kind of halls. It meant that there could be extreme dynamics, which there weren't in some of these other kinds of music. Quiet parts could be heard that would have been drowned out by all the gossiping and shouting. But because of the reverberation in those rooms like Carnegie Hall, the music had to be maybe a little less rhythmic and a little more textural. (Music: "Symphony No. 8 in E Flat Major" by Gustav Mahler) This is Mahler. It looks like Bob Dylan, but it's Mahler. That was Bob's last record, yeah.

(Laughter)

Popular music, coming along at the same time. This is a jazz band. According to Scott Joplin, the bands were playing on riverboats and clubs. Again, it's noisy. They're playing for dancers. There's certain sections of the song -- the songs had different sections that the dancers really liked. And they'd say, "Play that part again." Well, there's only so many times you can play the same section of a song over and over again for the dancers. So the bands started to improvise new melodies. And a new form of music was born. (Music: "Royal Garden Blues" by W.C. Handy / Ethel Waters) These are played mainly in small rooms. People are dancing, shouting and drinking. So the music has to be loud enough to be heard above that. Same thing goes true for -- that's the beginning of the century -- for the whole of 20th-century popular music, whether it's rock or Latin music or whatever. [ Live music ] doesn't really change that much.

It changes about a third of the way into the 20th century, when this became one of the primary venues for music. And this was one way that the music got there. Microphones enabled singers, in particular, and musicians and composers, to completely change the kind of music that they were writing. So far, a lot of the stuff that was on the radio was live music, but singers, like Frank Sinatra, could use the mic and do things that they could never do without a microphone. Other singers after him went even further. (Music: "My Funny Valentine" by Chet Baker) This is Chet Baker. And this kind of thing would have been impossible without a microphone. It would have been impossible without recorded music as well. And he's singing right into your ear. He's whispering into your ears. The effect is just electric. It's like the guy is sitting next to you, whispering who knows what into your ear.

So at this point, music diverged. There's live music, and there's recorded music. And they no longer have to be exactly the same. Now there's venues like this, a discotheque, and there's jukeboxes in bars, where you don't even need to have a band. There doesn't need to be any live performing musicians whatsoever, and the sound systems are good. People began to make music specifically for discos and for those sound systems. And, as with jazz, the dancers liked certain sections more than they did others. So the early hip-hop guys would loop certain sections. (Music: "Rapper's Delight" by The Sugarhill Gang) The MC would improvise lyrics in the same way that the jazz players would improvise melodies. And another new form of music was born.

Live performance, when it was incredibly successful, ended up in what is probably, acoustically, the worst sounding venues on the planet: sports stadiums, basketball arenas and hockey arenas. Musicians who ended up there did the best they could. They wrote what is now called arena rock, which is medium-speed ballads. (Music: "I Still Haven't Found What I'm Looking For" by U2) They did the best they could given that this is what they're writing for. The tempos are medium. It sounds big. It's more a social situation than a musical situation. And in some ways, the music that they're writing for this place works perfectly.

So there's more new venues. One of the new ones is the automobile. I grew up with a radio in a car. But now that's evolved into something else. The car is a whole venue. (Music: "Who U Wit" by Lil' Jon & the East Side Boyz) The music that, I would say, is written for automobile sound systems works perfectly on it. It might not be what you want to listen to at home, but it works great in the car -- has a huge frequency spectrum, you know, big bass and high-end and the voice kind of stuck in the middle. Automobile music, you can share with your friends.

There's one other kind of new venue, the private MP3 player. Presumably, this is just for Christian music. (Laughter) And in some ways it's like Carnegie Hall, or when the audience had to hush up, because you can now hear every single detail. In other ways, it's more like the West African music because if the music in an MP3 player gets too quiet, you turn it up, and the next minute, your ears are blasted out by a louder passage. So that doesn't really work. I think pop music, mainly, it's written today, to some extent, is written for these kind of players, for this kind of personal experience where you can hear extreme detail, but the dynamic doesn't change that much.

So I asked myself: Okay, is this a model for creation, this adaptation that we do? And does it happen anywhere else? Well, according to David Attenborough and some other people, birds do it too -- that the birds in the canopy, where the foliage is dense, their calls tend to be high-pitched, short and repetitive. And the birds on the floor tend to have lower pitched calls, so that they don't get distorted when they bounce off the forest floor. And birds like this Savannah sparrow, they tend to have a buzzing (Sound clip: Savannah sparrow song) type call. And it turns out that a sound like this is the most energy efficient and practical way to transmit their call across the fields and savannahs. Other birds, like this tanager, have adapted within the same species. The tananger on the East Coast of the United States, where the forests are a little denser, has one kind of call, and the tananger on the other side, on the west (Sound clip: Scarlet tanager song) has a different kind of call. (Sound clip: Scarlet tanager song) So birds do it too.

And I thought: Well, if this is a model for creation, if we make music, primarily the form at least, to fit these contexts, and if we make art to fit gallery walls or museum walls, and if we write software to fit existing operating systems, is that how it works? Yeah. I think it's evolutionary. It's adaptive. But the pleasure and the passion and the joy is still there. This is a reverse view of things from the kind of traditional Romantic view. The Romantic view is that first comes the passion and then the outpouring of emotion, and then somehow it gets shaped into something. And I'm saying, well, the passion's still there, but the vessel that it's going to be injected into and poured into, that is instinctively and intuitively created first. We already know where that passion is going. But this conflict of views is kind of interesting.

The writer, Thomas Frank, says that this might be a kind of explanation why some voters vote against their best interests, that voters, like a lot of us, assume, that if they hear something that sounds like it's sincere, that it's coming from the gut, that it's passionate, that it's more authentic. And they'll vote for that. So that, if somebody can fake sincerity, if they can fake passion, they stand a better chance of being selected in that way, which seems a little dangerous. I'm saying the two, the passion, the joy, are not mutually exclusive.

Maybe what the world needs now is for us to realize that we are like the birds. We adapt. We sing. And like the birds, the joy is still there, even though we have changed what we do to fit the context.

Thank you very much.

(Applause)

このライブハウスは 私が若い頃 自作の曲を 初めて演奏した場所です とても音響効果の いい会場でした 壁は全部デコボコで ゴミだらけなんだけど 音は非常に良かったです この曲は そこで録られたものです (音楽) まあこの写真はトーキング・ヘッズ じゃないんだけど (曲:クリーンブレイク 作:トーキング・ヘッズ) あの場所では 言葉が良く聞き取れて 歌詞もよく理解してもらえた サウンドシステムもそこそこで 残響音もあまりなかった なのでリズムも ちゃんと正確に聴こえ きっちり演奏できました 他の地域にも似たような場所があります これはナッシュビルのトゥッティーズです 違うタイプの音楽を扱ってましたが 建物の構造や形は よく似ていました クラブ常連の行動も似たようなもので トゥッティーズや CBGBで演奏するとき バンドは暴れたり叫んだり 好き勝手なことをする観客に 目一杯音量を上げて 対抗してましたね

その後私は もう少し高級な会場で 演奏するようになりました ここLAのディズニーホールや カーネギーホールといった場所です すごくエキサイティングでしたが そのとき気づいたんです その当時や過去に作った 音楽はこういったホールでは それほどいい音に 聴こえないということに 何とかやってみましたが ホールではどうも当時の私の作品が しっくり聴こえて こないんです なので自問しました 私の作品は 空間を意識していたか 場所や会場のことを考え 曲を書いていただろうか これは創作のひとつの方法ではないのか 私達は何かモノを創るとき 場所や背景のことを考えているのかと

さて アフリカ音楽です (曲:ウェンレンガ / オムニバス) ポピュラーミュージックのルーツの大部分が 西アフリカを起源とすることはご存知ですね アフリカの音楽は そう 楽器も 複雑なリズムも 演奏法も 情景や背景も すべてが完璧なんです その環境にぴったり合っている 大きな会場が 反響してリズムを狂わせることもないです 楽器には十分な音量があるので アンプやその他がなくても聴こえます 機材トラブルもなし アフリカの環境に対し完璧なのです でも 次のような状況には 合わないでしょう ゴシック式の大聖堂です (曲:御身よりほかにわれは 作:トマス・タリス) ゴシック式大聖堂にはこういう音楽が合います 音階の変更はせず 音色は長く伸ばされます リズムもほとんどありません 建築が音楽を引き立たせています 実際に音質を向上させるのです この空間でバッハは 作曲していました これがオルガンです 大聖堂のように大きくないので 複雑な音楽を書くことが出来ました 大きな不協和音のリスクなく キーを変えるという 革新をすることが出来たんです (曲:幻想曲「イエスわが喜び」 作:バッハ)

これはその少し後 こういう場所でモーツァルトは曲を書いてました 確か1770年あたりだったと思います 空間が小さくなり反響音も少ないので 本当に装飾的な音楽が書けました 複雑ですが うまくいってます (曲:ピアノソナタ第13番 作:モーツァルト) 空間にぴったり合っている これはスカラ座です ほぼ同時期の建物です 1776年に建てられたと思います これらのオペラハウスが建てられた頃の観客は 歓声をあげるのが普通でした 飲食をしながらステージに向かって歓声を送りました CBGBとかでみんながやるようにね アリアが好きだと思ったら 大声をあげて アンコールを促しました 終演後だけじゃなく ショーの途中でも突然ね (笑) でも それがオペラってものだったんですよ これはワグナーが自分の為に建てたオペラハウスです そんなに大きな空間じゃなくて ここよりも小さいぐらいかな でもね ワグナーは革新を起こました もっと大きな楽団が欲しかった 豪勢に見せたかったんですね オーケストラ・ピットを大きくすることで ローエンドの楽器を加えることができた (曲:『ローエングリン』第3幕への前奏曲 作:ワグナー)

さて これはカーネギーホールです ご存知のようにこの手のホールが主流になりました サイズは大きくなり カーネギーは特に 他のシンフォニーホールよりも大きいですね こういった場所はスカラ座より よく音が反響します この頃ニューヨーカーに 執筆中だったアレックス・ロス曰く 観客はショーの間 静かにして 食事 飲酒 歓声や ひそひそ話などをしないことが ルールになってきたと いうことです 会場は静かになりました ホールの反響と静けさにより 今までとは違う種類の音楽が そこにぴったりと来るようになりました この種の音楽に今までなかったような 極端な強弱法が 使用できるようになったのです 今まで世間話や歓声によって 掻き消されていた静かなパートが 聞こえるようになりました 反響音があったせいで カーネギーホールのような場所では 音楽はややリズムを抑え 構成的に ならざるを得ませんでした (曲:交響曲第8番変ホ長調 作:マーラー) これはマーラーです ボブ・ディランに見えるけど マーラーです 写真はボブの最新作だね

(笑)

この頃ポピュラー音楽が出現しました これはジャズバンドですね スコット・ジョップリンによると バンドは リバーボートやクラブで演奏していた またもや 騒がしい場所だね ダンスの伴奏をしてたのだけど その中に ダンサー達のお気に入りの箇所があった で 「今のとこもう一回」って言われる ダンサーの為に何回も 同じ箇所ばかり演奏させられると しまいに飽きて バンドが即興でメロディーを作るようになった 新しい音楽が生まれた瞬間でした (曲:ロイヤル・ガーデン・ブルース 作:ハンディ/ウォーターズ) ジャズが演奏されたのは小さな会場ばかりで みんな踊り 声を上げ 酒を飲んでいた だからそれより大きな音で演奏しないと ちゃんと聴こえなかったんです これは20世紀の初めでしたが 同じことは この世紀全体のポピュラー音楽にも言えます ロックとかラテンミュージックといったね ライブ音楽に関してあまり変化はないです

20世紀も三分の一を過ぎる頃には変化が起こり ラジオが 音源の主流になり マイクが音楽を 進化させる一要因となったのです マイクの存在がミュージシャンや作曲家 そして特に歌手たちに 全く違ったタイプの曲を書く事を 可能にさせたのです ラジオで掛けられる曲の多くは生演奏でしたが フランク・シナトラのようなシンガーには マイクなしでは 絶対出来なかったようなことが 出来るようになりました シナトラ後のシンガー達には 変化はさらに顕著でした (曲:マイ・ファニー・バレンタイン 作:チェット・ベイカー) チェット・ベイカーです こういう風に歌うことは マイクなしでは不可能でした 録音技術なしにも不可能だったでしょう 彼の歌声は右側から聞こえてきます 彼のささやきが耳に入ってきます この効果はマイクによるものです まるであなたの横に座っているかのように ささやきが聞こえてきます

そしてこの時点で 音楽は二つに分かれます ライブ・ミュージックと レコーディング・ミュージックです もう双方が全く同じである必要はないのです そして今 この写真のような会場もあります ディスコですね バーにはジュークボックスがあって そこではバンドはもう必要ありません 生バンドの演奏の類は もはや必要ないのです 音響システムはいいですね そしてディスコや音響システムに 特別に合わせた 音楽が創られ始めました また ジャズのように ダンサー達は曲のある一部分を 他の箇所より気に入ってました 初期ヒップホップが曲の一部を繰り返すようになった所以です (曲:ラッパーズ・ディライト 作:シュガーヒル・ギャング) ジャズ・ミュージシャンが即興演奏したように MCも即興でラップするようになりました またここで 新しい音楽が生まれたのです

ライブが人気を博すようになると キャパ的理由から 音響的に地上最悪の スタジアムやバスケットボールアリーナ ホッケーアリーナなどで 演奏する羽目になります そうなったミュージシャン達は全力を尽くしました 今ではアリーナロックと呼ばれる ミディアムバラードを書き始めたのです (曲:終りなき旅 作:U2) 彼らは曲作りに 最善を尽くそうとしたのですね ミディアムテンポで壮大に聞こえる曲です。 これは音楽的状況からというより 社会的状況に迫られたものです こういった会場のために書かれた曲は 彼らの状況にも ぴったりなわけです

そしてさらに新しい空間が出来ました 車の中もその一つですね 私はカーラジオと一緒に育ちました しかし今はラジオも進化しました 車はライブ会場そのものですね (曲:フーユーウィズ 作:リル・ジョン&ザ・イースト・サイド・ボーイズ ) 私は この音楽は 車向けに作られたと言いたい バッチリはまってますよね 家の中で聞きたいとは思わないかもしれないけど 車の中で聞くにはすごくいい 周波数スペクトラムが広範囲で 大きなベース音とハイエンド ボーカルはミドルレンジで留まってる 車で聞く音楽は友達とシェアできますからね

その他の新しい音楽の聞き方として MP3プレイヤーがあります おそらく このプレイヤーはクリスチャン専用でしょうね (笑) 音のひとつひとつがよく聞こえるので カーネギーホールとか 観客が静かにしている 場所で音楽を聴くようなものですね 別の言い方をすれば 西アフリカの音楽にも似ています MP3プレイヤーの音楽が静かになったとき 音量を上げますね すると次の瞬間 大音量の一節が流れ出し 鼓膜が破れそうになる これはあまりよくありません 特に最近の ポップミュージックにおいて ある程度はMP3プレイヤーを念頭に 曲が書かれているので ものすごく細部まで聞き取れるんですが 音のダイナミズムが余りないんです

そこで自問しました 私達が 環境に合わせることは 創作のひとつの方法だろうか 他の場所でも起こっているのだろうか デービッド・アッテンボローや他の人も言ってますが 鳥も同じだそうです あの木の枝にいる鳥は 葉っぱが密集している所では 鳴き声が高くなって 短く繰り返しがちになる傾向があります 地面に立っている時の鳴き声は 低い音になる傾向があるため 森の地面から飛び立つ時は 声の響きが増幅されにくいです サバンナスパロウという鳥は ブンブンと鳴く傾向が (サウンドクリップ: サバンナスパロウ) あります こういう鳴き方は 草原やサバンナで 仲間に呼びかける時に 最も実用的で エネルギー効率のいい 方法だということが分かっています 他に この風琴鳥という鳥のように 同じ種なのに別の鳴き方をする鳥もいます 風琴鳥はアメリカ東海岸の 少し深い森の中では こういう鳴き方をしますが 反対の西海岸では (サウンドクリップ: 赤風琴鳥) 違った鳴き方をします (サウンドクリップ: 赤風琴鳥) 鳥も環境に適応しています

そこで考えました これは創作のひとつの形だろうか 大まかな形でもいい 環境を頭に入れて曲を 書くのだろうか 美術館の壁に似合うアートを作るのか ソフトウェアを現存のOSに合わせて作れば 上手くいくのか そう 革新的なことだと思います 環境順応です しかし 楽しみや情熱 喜びは 失われません これは伝統的でロマンチックな 考え方とは真逆の考え方です ロマンチックな考え方では まず情熱があり 次に感情を流し込み それから詳細な形がつくられていきます この理論は まず型があって 最初に本能と直感で まず形を作り 後から情熱をそこに 注ぎ込んでいくという やり方です 情熱を注ぎ込む場所はもう決まっているのです まあ こういう考え方の違いも面白いですね

作家の トーマス・フランクは どうして有権者が 時として自らの支持と反した 投票をしてしまうのかという 説明をしています 私達のような多くの有権者は 誠実そうな言葉を 信頼できる 心からの 情熱からのものだと 思い込みがちです だから投票するのです もし誰か誠実さを装ったり 情熱を装うことが出来たら そういった方法で当選する チャンスも高くなるのです 少し危険ですよね 情熱と喜びは お互いに 相容れないものではないんです

今 私達も鳥達のようなものだと 気づく必要があるのでしょう 環境に適応し 歌う 環境に合わせて自分たちを変えても 鳥と同じく 私達も喜びを変わらず 持ち続けています

ありがとうございました

(拍手)

品詞分類

- 主語

- 動詞

- 助動詞

- 準動詞

- 関係詞等

TED 日本語

TED Talks

関連動画

アーティストは経済にどう貢献し、私たちは彼らをどう支えられるか?ハディ・エルデベック

2018.04.09

コンテンツを流行らせる要素とは?ダオ・グエン

2018.01.08

私がアートを制作するのは、伝統を受け継ぐタイムカプセルを作るためケイラ・ブリエット

2017.12.08

ニューヨーカー誌、象徴的な表紙イラストの舞台裏フランソワーズ・ムーリー

2017.08.17

とらえ難い心情を表す素敵な新語の数々ジョン・ケーニック

2017.03.31

2千本のおくやみ記事から学んだことラックス・ナラヤン

2017.03.23

メロドラマが教えてくれる4つの大げさな人生訓ケイト・アダムス

2017.01.03

音楽がもたらしたコンピューターの発明スティーヴン・ジョンソン

2016.12.09

Ideas worth dating -- デートする価値のあるアイデアレイン・ウィルソン

2016.10.30

購読解除の苦悩!ジェイムズ・ヴィーチ

2016.09.27

コスプレへの愛アダム・サヴェッジ

2016.08.23

「アンチ」を科学的に分類してみようネギン・ファルサド

2016.07.05

データで描く、示唆に富む肖像画ルーク・デュボワ

2016.05.19

詐欺メール 返信すると どうなるかジェイムズ・ヴィーチ

2016.02.01

世界中の国の本を1冊ずつ読んでいく私の1年アン・モーガン

2015.12.21

日常の音に隠された思いがけない美とはメクリト・ハデロ

2015.11.10

洋楽 おすすめ

RECOMMENDS

洋楽歌詞

ステイザ・キッド・ラロイ、ジャスティン・ビーバー

洋楽最新ヒット2021.08.20

スピーチレス~心の声ナオミ・スコット

洋楽最新ヒット2019.05.23

シェイプ・オブ・ユーエド・シーラン

洋楽人気動画2017.01.30

フェイデッドアラン・ウォーカー

洋楽人気動画2015.12.03

ウェイティング・フォー・ラヴアヴィーチー

洋楽人気動画2015.06.26

シー・ユー・アゲインウィズ・カリファ

洋楽人気動画2015.04.06

シュガーマルーン5

洋楽人気動画2015.01.14

シェイク・イット・オフテイラー・スウィフト

ポップス2014.08.18

オール・アバウト・ザット・ベースメーガン・トレイナー

ポップス2014.06.11

ストーリー・オブ・マイ・ライフワン・ダイレクション

洋楽人気動画2013.11.03

コール・ミー・メイビーカーリー・レイ・ジェプセン

洋楽人気動画2012.03.01

美しき生命コールドプレイ

洋楽人気動画2008.08.04

バッド・デイ~ついてない日の応援歌ダニエル・パウター

洋楽人気動画2008.05.14

サウザンド・マイルズヴァネッサ・カールトン

洋楽人気動画2008.02.19

イッツ・マイ・ライフボン・ジョヴィ

ロック2007.10.11

アイ・ウォント・イット・ザット・ウェイバックストリート・ボーイズ

洋楽人気動画2007.09.14

マイ・ハート・ウィル・ゴー・オンセリーヌ・ディオン

洋楽人気動画2007.07.12

ヒーローマライア・キャリー

洋楽人気動画2007.03.21

オールウェイズ・ラヴ・ユーホイットニー・ヒューストン

洋楽人気動画2007.02.19

オネスティビリー・ジョエル

洋楽人気動画2005.09.16